The Philo-Practice Agora

The electronic library for philosophical practitioners from around the world

JEREMY BENTHAM

Right actions bring happiness

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), an English philosopher and social reformer, was one of the main thinkers in the history of modern ethics. He was the first to formulate the principles of Utilitarianism, according to which actions are right or wrong depending only on the happiness (“utility”) or unhappiness which they produce. This idea was later developed by his student, the philosopher John Stuart Mill, so that philosophers nowadays often quote Mill more than Bentham.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), an English philosopher and social reformer, was one of the main thinkers in the history of modern ethics. He was the first to formulate the principles of Utilitarianism, according to which actions are right or wrong depending only on the happiness (“utility”) or unhappiness which they produce. This idea was later developed by his student, the philosopher John Stuart Mill, so that philosophers nowadays often quote Mill more than Bentham.

Bentham was born in London to a rich family, and as a little child showed special intellectual abilities. He studied law, and later envisioned several social reforms regarding prisons, human rights, and other matters. At first his ideas were not appreciated, but later in life his influence on British society grew. He corresponded with many thinkers, wrote many books, and founded an influential journal. He died at the age of 84, leaving behind thousands of written pages.

The following text is adapted from Chapter 1 of Bentham’s book An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789). Here Bentham defines the basic principle of the Utilitarian approach, the principle of utility: that expected pleasure (or happiness) is what (a) determines whether an action is morally right or wrong, and (b) motivates people to act. An action is morally right, therefore, if it maximizes the pleasure (or happiness, or what he calls “utility”) of the people involved.

I. Nature has placed mankind under the rule of two sovereign masters: pain and pleasure. It is only these two that point out what we OUGHT to do, and also to determine what we SHALL do. Attached to their throne are, on the one hand the standard of right and wrong, and on the other hand the chain of causes and effects. They govern us in everything we do, in everything we say, in everything we think. Every effort we can make to throw off their rule will only serve to demonstrate and confirm this. A person may pretend in words to reject their empire, but in reality he will remain subject to it. The principle of utility recognizes this subjection, and it makes it the foundation of that system – whose goal is to nurture the fabric of happiness with the hands of reason and of law. Systems which attempt to question this principle, deal with sounds instead of sense, with caprice instead of reason, with darkness instead of light.

But enough of metaphor and poetics! It is not by such means that moral science is to be improved.

II. The principle of utility is the foundation of the present work: It will be proper, therefore, to start with an explicit and determinate account of what it means. The principle of utility is the principle which approves or disapproves of any action whatsoever according to the tendency which it seems to have to increase or decrease the happiness of the people under consideration. Or, what is the same thing in other words: to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say “any action whatsoever,” and therefore not only actions of a private individual, but also every act of government.

II. The principle of utility is the foundation of the present work: It will be proper, therefore, to start with an explicit and determinate account of what it means. The principle of utility is the principle which approves or disapproves of any action whatsoever according to the tendency which it seems to have to increase or decrease the happiness of the people under consideration. Or, what is the same thing in other words: to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say “any action whatsoever,” and therefore not only actions of a private individual, but also every act of government.

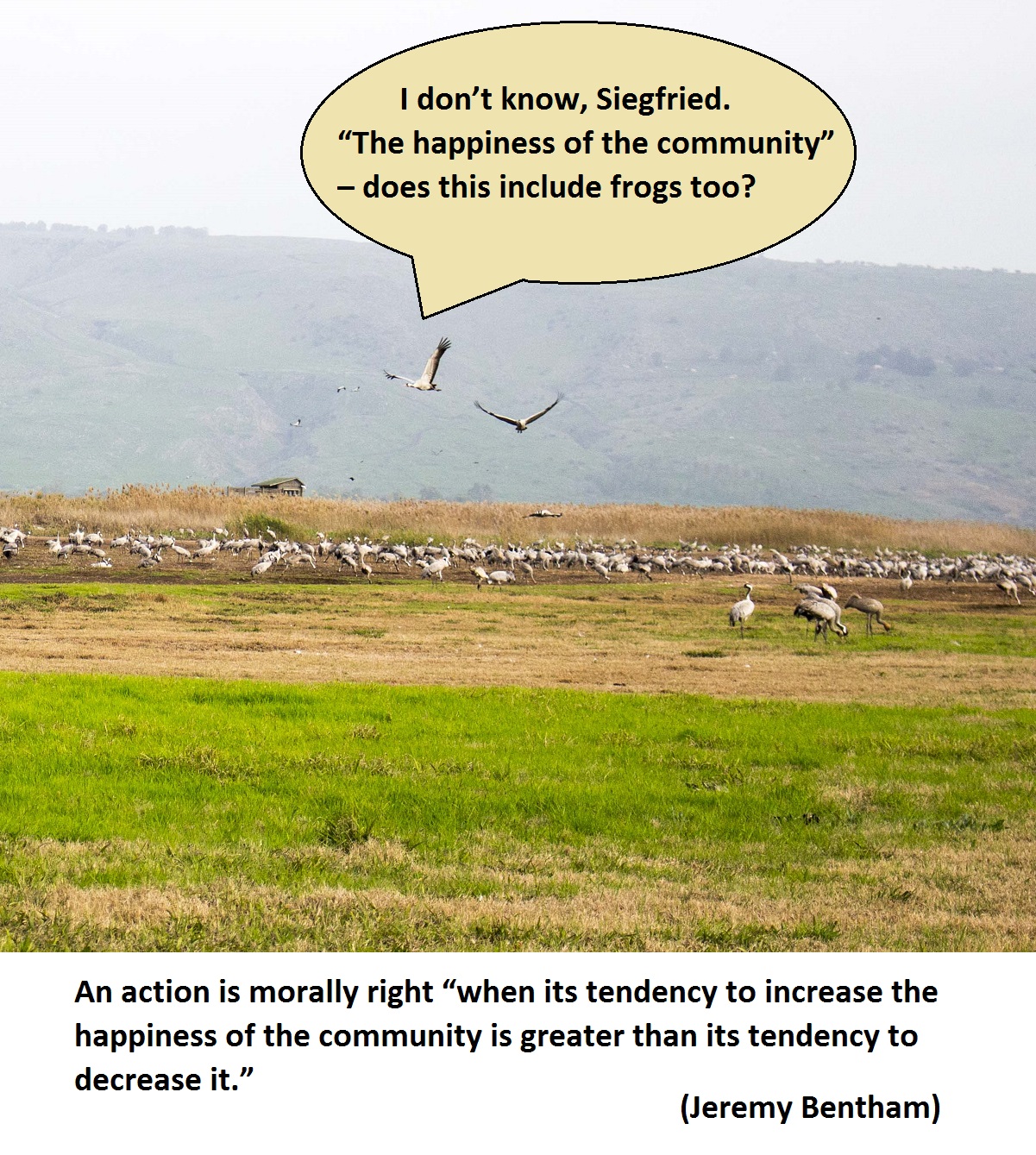

III. By “utility” I mean that property of any object which tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness (all this comes to the same thing) or (what comes again to the same thing) to prevent the happening of mischief, pain, evil, or unhappiness to the people under consideration. If they are the community in general, then the happiness of the community; if it is a particular individual, then the happiness of that individual.

IV. The interest of the community is one of the most general expressions in the language of morality – no wonder that its meaning is often lost. When it has a meaning, it is this: The community is an imaginary body, composed of the individual persons who are considered its members. What is, then, the interest of the community? It is the sum of the interests of the individual members who compose it.

VI. An action may be said to agree with the principle of utility […] when its tendency to increase the happiness of the community is greater than its tendency to decrease it.

VI. An action may be said to agree with the principle of utility […] when its tendency to increase the happiness of the community is greater than its tendency to decrease it.

IX. A person is a supporter of the principle of utility, when his approval or disapproval of any action is determined by, and proportional to, the tendency which he thinks the action has to increase or decrease the happiness of the community. Or, in other words, to its agreement or disagreement with the laws of utility.

X. We may say this about an action which agrees with the principle of utility: Either it is an action that ought to be done, or at least it is not an action that ought not to be done. One may also say that it is right – it should be done; or at least that it is not wrong to do it. That it is a right action, or at least that it is not a wrong action. When interpreted this way, the words “ought,” and “right” and “wrong,” and others of that kind, have a meaning. If not, they have no meaning.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.