|

An issue for reflection

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE FREE?

|

|

|

|

Maria Tillmanns is a philosopher (PhD) from San Diego, California. Maria was especially active in the Dutch PP movement in the 1990s.

|

| |

|

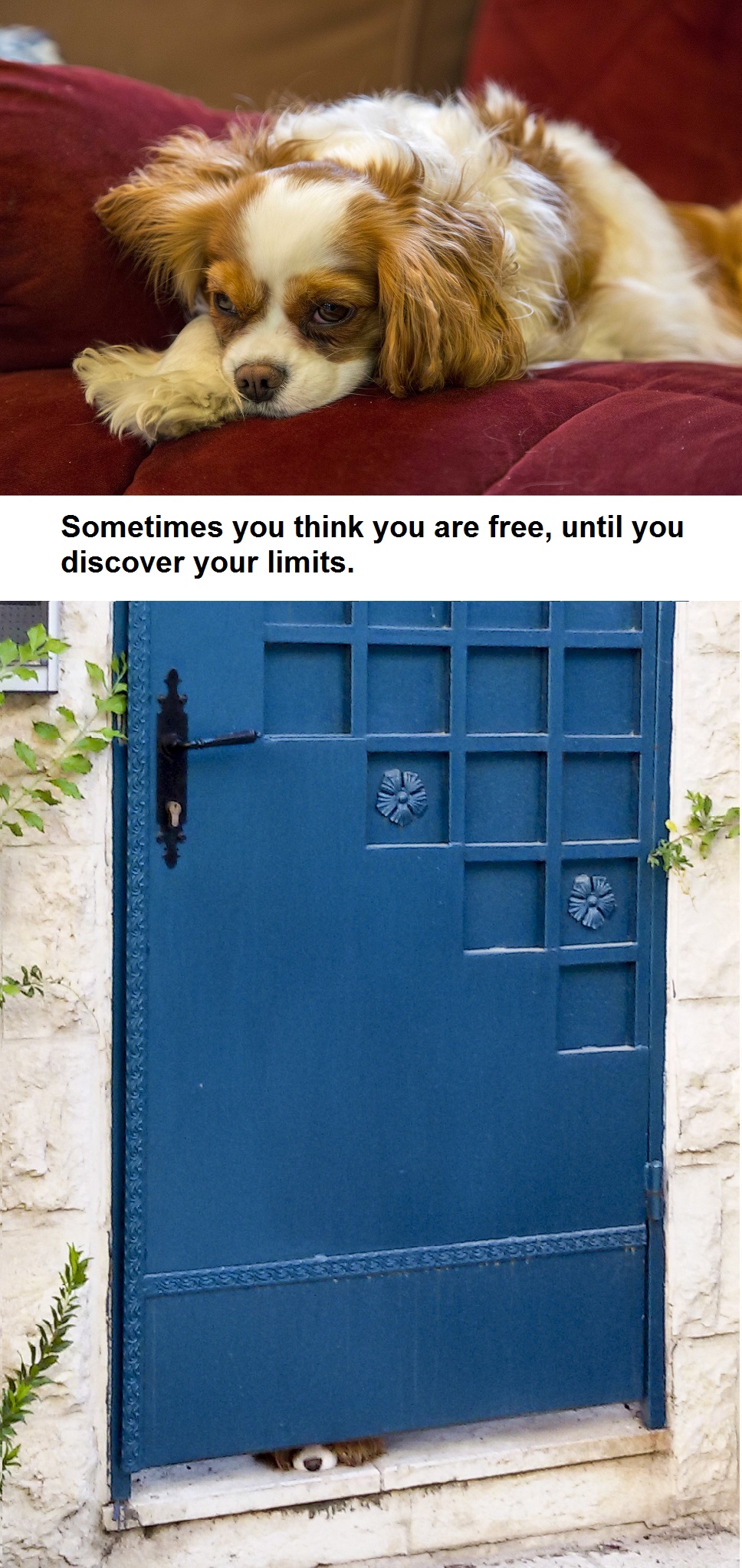

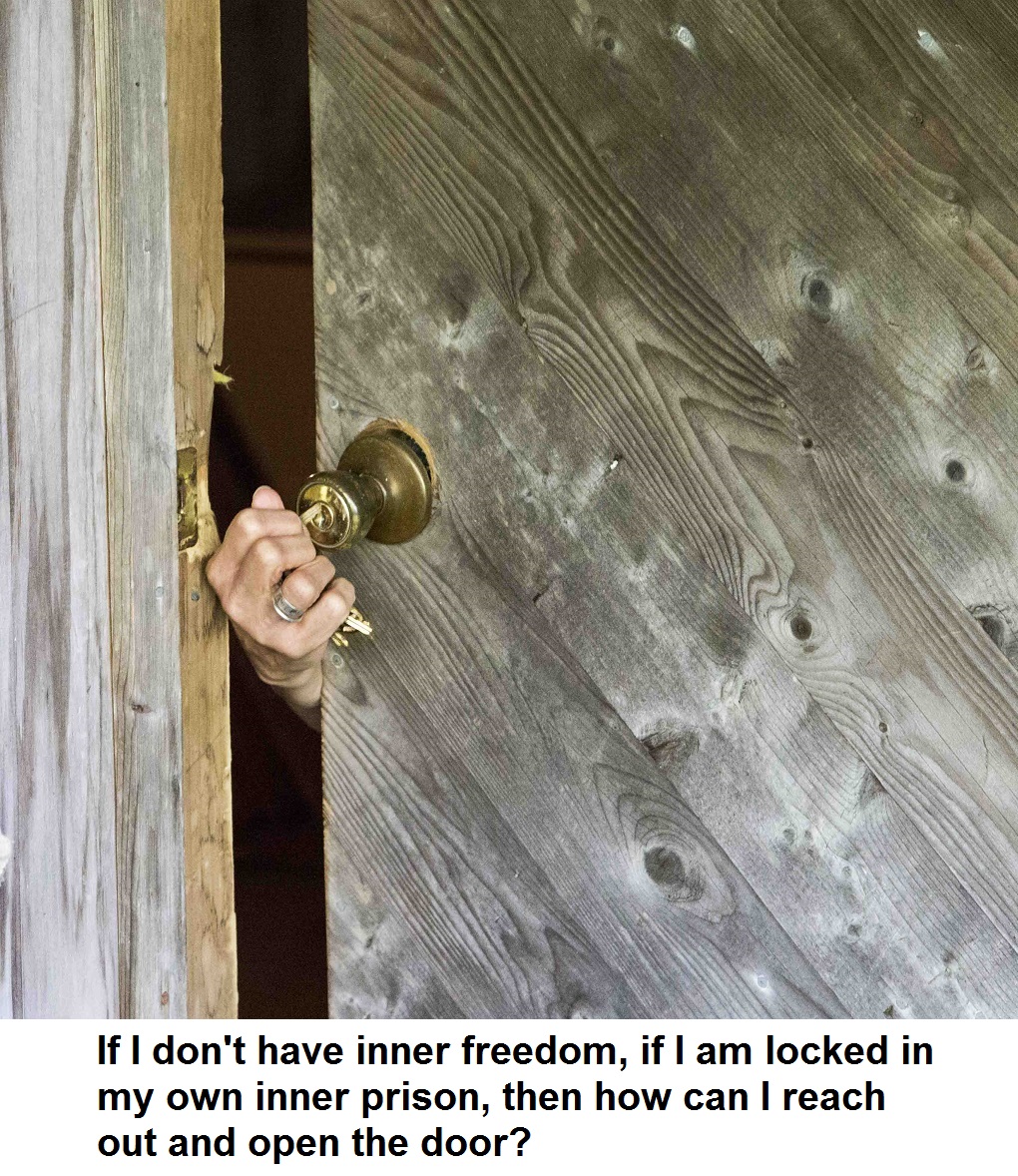

Announcing a Competition

The above photo needs a caption (a text)! Send us your suggestion! A caption can be a title, or the words of the person behind the wall, etc.

Maximum length: 30 words.

Send to: Ran, Carmen, or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Deadline: The third Saturday of the month.

The Agora team will select the most philosophical, and/or smartest, and/or funniest caption. The winning caption will be placed under the photo, together with the winner's name.

|

|

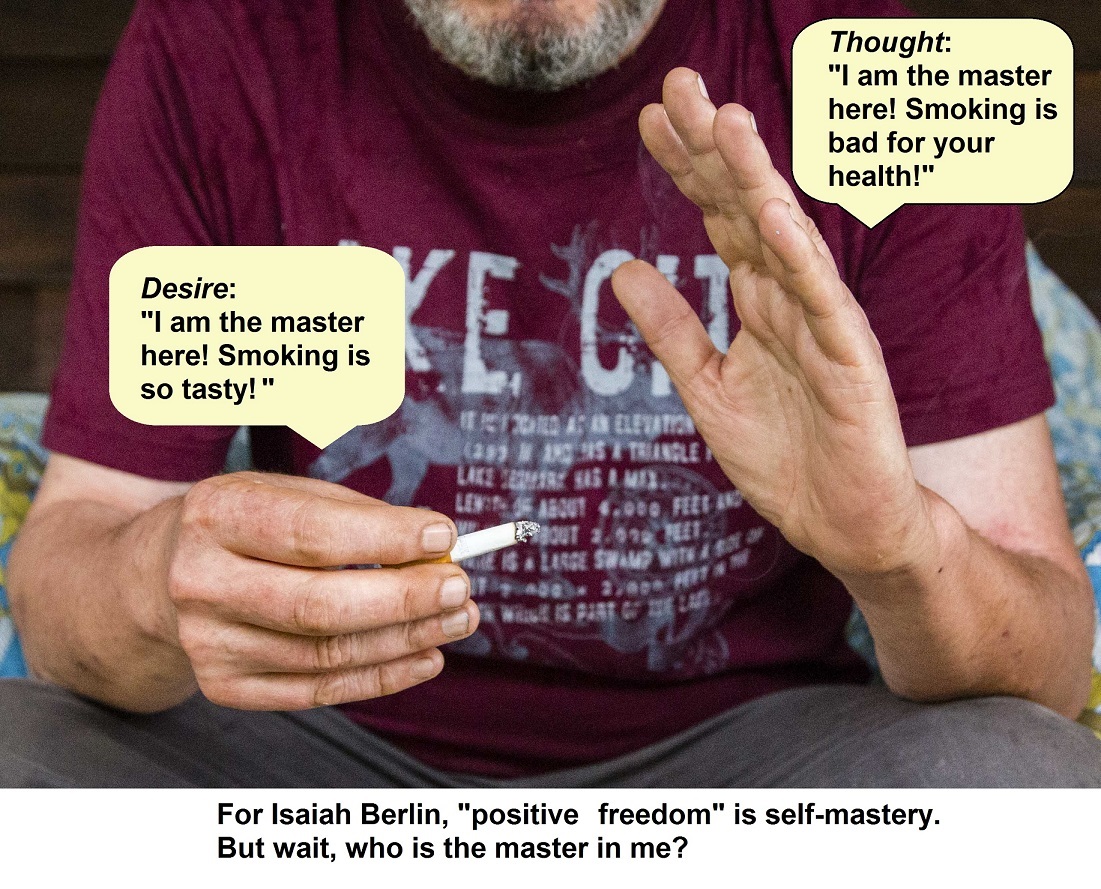

“He was so intimidating, I couldn’t find the courage to say No.”

“I am a shy person, I couldn’t bring myself to dance with everybody watching me.”

“She smiled at me and her smile pierced my heart. I couldn’t open my mouth.”

“I was dying for a cigarette. I couldn’t resist buying a pack.”

How can my own feelings– my fear, my shyness, my anxiety, my desire –force me to act against my will? After all, they are part of me! So how can they be my prison?

Besides, if my feelings dominate me, then who is the "me" who is dominated by them? If my feelings are my prison, then who is the prisoner?

In short, what does it mean to be free?

|

|

|

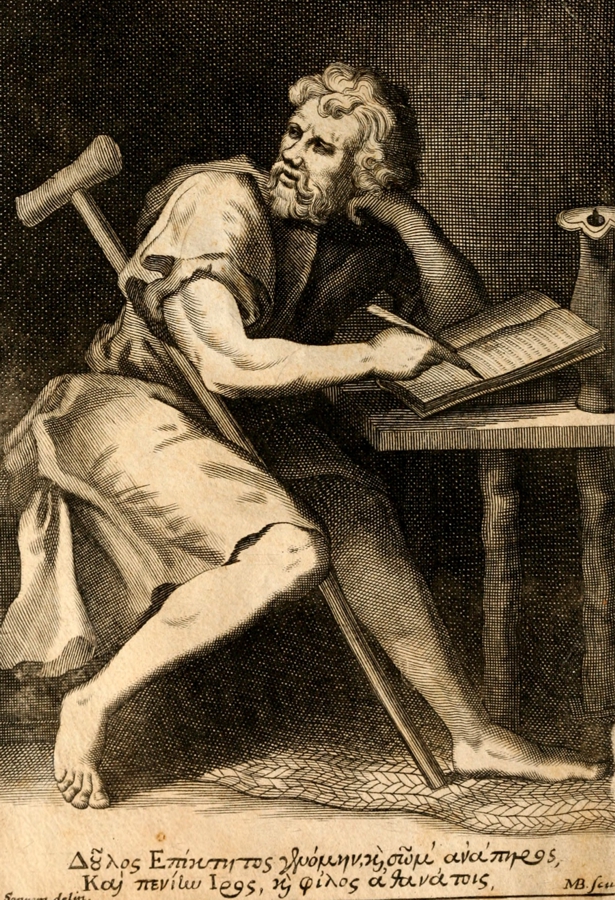

September Week 1 quotation

EPICTETUS

|

|

Freedom from wanting things not in our control

Epictetus (55-135 AD) was a Stoic philosopher. He was born a slave, but was educated by his rich masters. He was freed as a young man, and began teaching philosophy in Rome. When the emperor banished all philosophers from Rome, he went to Nicopolis, Greece, where he lived and taught until his death.

Like other Stoics, Epictetus believed that many events in life are outside our control. We may plan as much as we want, and we may take as many precautions as we want, but our plans can always be disrupted by unforeseen events like sickness, accidents, chance, and other people’s actions. This means that in most areas of life we do not have full control, and therefore we are not free. There is only one place where we can be, according to Epictetus, fully free: In our inner world – in our decisions, our will, our intentions, our expectations. Nothing can stop me from making a certain decision, nothing can stop me from wanting something or not wanting it. I have complete control over my will and my thoughts. Like other Stoics, Epictetus believed that many events in life are outside our control. We may plan as much as we want, and we may take as many precautions as we want, but our plans can always be disrupted by unforeseen events like sickness, accidents, chance, and other people’s actions. This means that in most areas of life we do not have full control, and therefore we are not free. There is only one place where we can be, according to Epictetus, fully free: In our inner world – in our decisions, our will, our intentions, our expectations. Nothing can stop me from making a certain decision, nothing can stop me from wanting something or not wanting it. I have complete control over my will and my thoughts.

Therefore, in order to be free, I must not depend on things outside my control, in other words on things outside me. I must not be attached to my house, to my reputation, my money, even my friends and family. I may try to do my family duties and social duties, but if misfortune strikes and my efforts fail, then I must accept this in peace and without complaint, without anger, without frustration. I accept the loss of my money, or of my house, or of my job, because I do not depend on them – I am free. I am not a slave to what I possess.

The following texts are adapted from two books, both of them compiled from Epictetus’ lectures by his student Arrian. Epictetus tells us here that freedom depends on our inner attitude, not on external conditions.

The Discourses

The man who is not under restraint is free, and for him things are exactly as he wishes them to be. But he who can be restrained or compelled or hindered, or thrown into any circumstances against his will, is a slave. But who is free from restraint? He who desires nothing that belongs to others. And what are the things which belong to others? The things which are not in our power to have or not to have, or to have of a certain kind, or in a certain manner. Therefore, the body belongs to another, the parts of the body belong to another, possession belongs to another… This road leads to freedom; that is the only way of escaping from slavery.

[...]

Diogenes was free. How was he free?

- Not because he was born of free parents, but because he was himself free, because he had cast off all the handles of slavery, and it was not possible for any man to lay hold of him or to enslave him. He had everything easily loosed, everything only hanging to him. If you laid hold of his property, he would rather let it go and let it be yours than follow you for it: if you laid hold of his leg, he would let go his leg; if of all his body, all his poor body; his intimates, friends, country, just the same… These were the things which permitted him to be free.

The Enchiridion

1. Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, or in short, whatever is our own action. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, or in short, whatever is not our own action.

The things in our control are by nature free, unrestrained, unhindered; but those not in our control are weak, slavish, restrained, belonging to others.

10. If you see an attractive person, you will find that self-restraint is the ability you have against your desire. If you are in pain, you will find fortitude. If you hear unpleasant language, you will find patience. When you are accustomed to this, things will not hurry you away along with them.

11. Never say about anything "I have lost it"; but "I have returned it." Is your child dead? It is returned. Is your wife dead? She is returned. Is your estate taken away? Well, isn’t it likewise returned?

"But he who took it away is a bad man!"

What difference is it to you who the giver assigns to take it back? While he gives it to you to possess, take care of it; but don't view it as your own, just as travelers view a hotel.

14. If you want your children and wife and friends to live forever, you are stupid. Because you wish to be in control of things which you cannot control, you wish that things that belong to others would be your own... Whoever would be free, let him wish nothing, let him decline nothing which depends on others, or else he must necessarily be a slave.

15. Remember that you must behave in life like at a dinner party. Is anything brought around to you? Put out your hand and take your share with moderation. Does it pass by you? Don't stop it. Is it not yet come? Don't stretch your desire towards it, but wait till it reaches you. Do this with regard to children, to a wife, to public posts, to riches, and you will eventually be a worthy partner of the feasts of the gods.

17. Remember that you are an actor in a drama, of whatever kind the author wished to make it. If it is short, then short; if it is long, then long. If he wishes you to act the role of a poor man, or a cripple, or a governor, or a private person, make sure that you act it properly. Because this is your task, to act well the character that was assigned you. To choose your part is somebody else’s business..

19. … Don't wish to be a general, or a senator, or a consul, but to be free; and the only way to this is to have contempt for things that are not in our control.

|

REFLECTING ON EPICTETUS’ TEXT:

Epictetus tells us that in order to be free, you must not be attached to anything which is not fully in your control. If you depend on something that is not in your control, then you are a slave to external conditions. Freedom therefore means complete inner independence.

Epictetus knew that it is extremely difficult to achieve such independence. He therefore devised exercises to develop our ability to be emotionally unattached. It is a good idea to try some of his exercises, in order to understand his approach concretely, not just in theory.

One of his exercises involves the imagination: Sit quietly and close your eyes. Imagine that your favorite small object – your mug, or poster, or photo – is destroyed. Imagine your emotional reaction, and try imagining yourself responding with complete calmness and equanimity. Next, imagine that a more valuable object is destroyed – your computer, or your car. And again, imagine yourself responding calmly. Next, imagine a bigger disaster – a serious sickness for example, or your house burning down – and your calm response. And so on. Does this give you a sense of inner freedom?

Another exercise you could do is to observe yourself in everyday moments. Whenever you catch yourself responding with frustration or anger, note this fact, and also try to calm yourself down and feel peaceful and indifferent. Does this give you a sense of inner freedom?

After doing these exercises, you will be better ready to assess Epictetus' philosophy of freedom. Do you find his approach acceptable? Or, at least, do you accept certain aspects of his view? Would you modify his philosophy of freedom? Or reject it altogether? And if so, what exactly are your reasons?

|

|

|

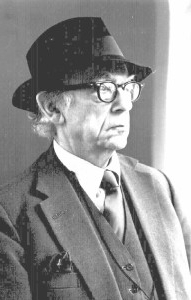

September Week 2 quotation

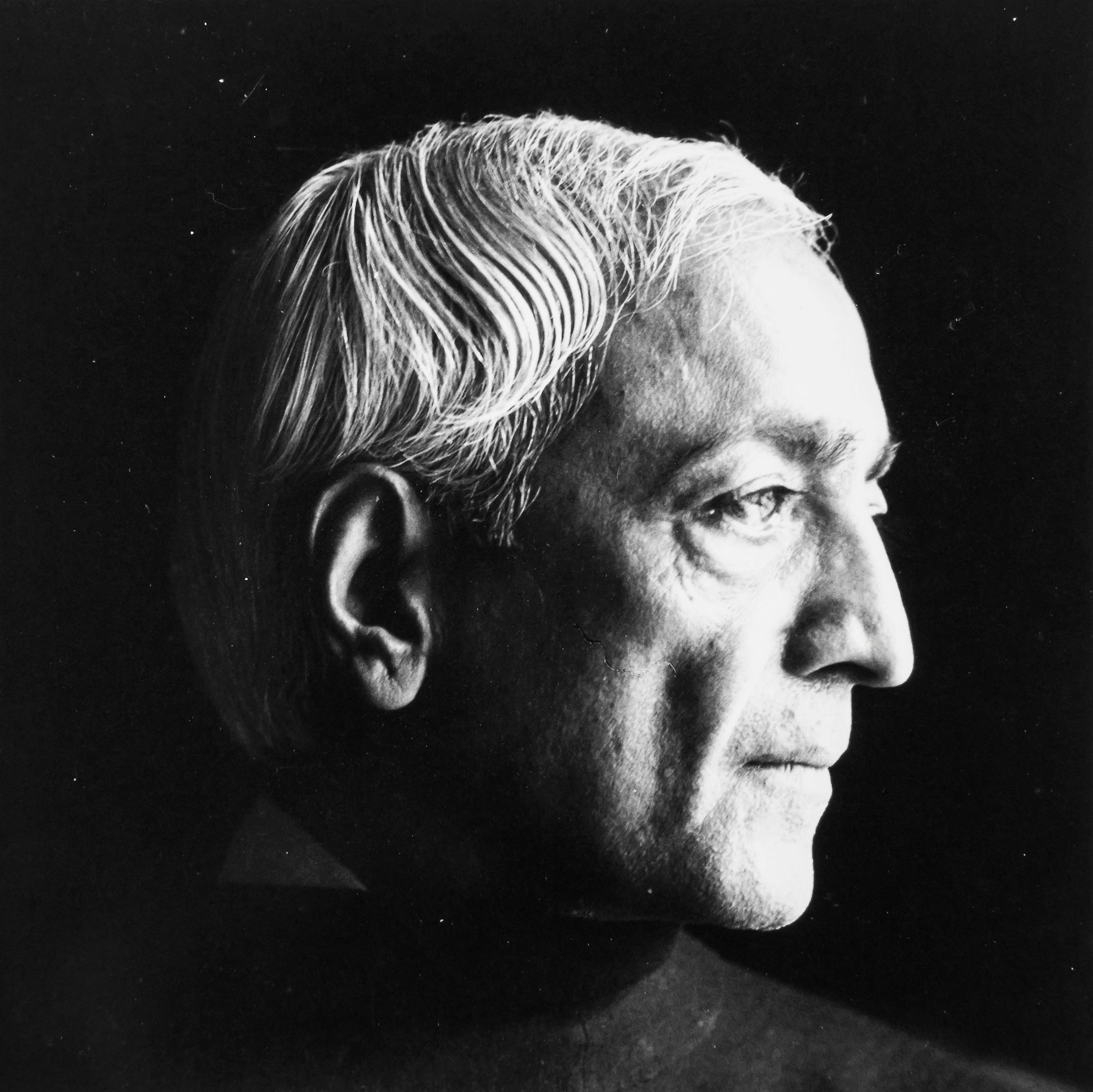

ISAIAH BERLIN

|

|

Freedom from and freedom to

Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) grew up in Latvia and Russia, but because of anti-Semitism his Jewish family moved to Britain in 1921. He became a philosophy professor at Oxford University, and is popularly known for his essay “Two concepts of liberty.”

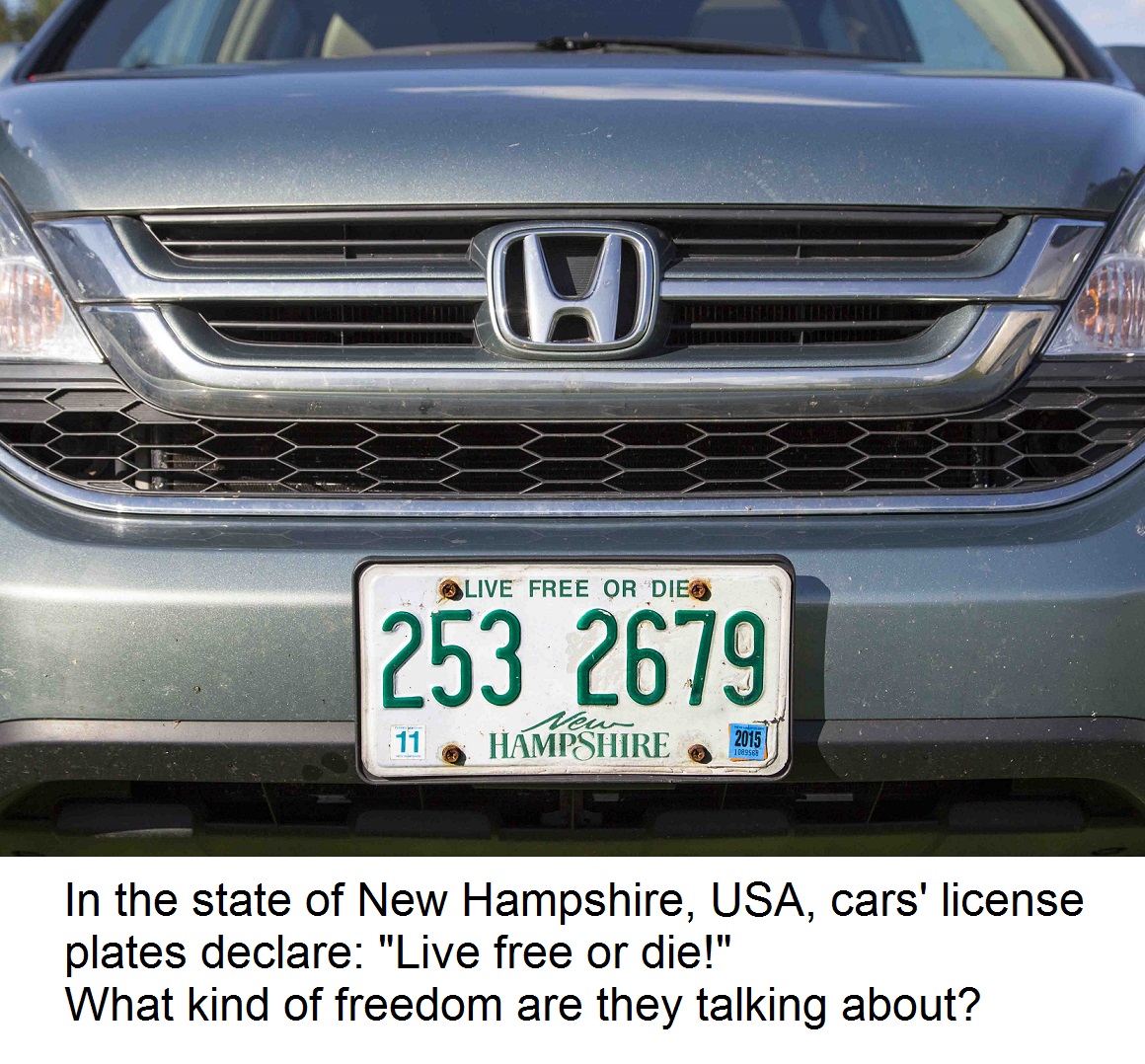

The following passages are adapted from a famous essay by Isiah Berlin, "Two Concepts of Liberty," delivered at Oxford University in England in 1958, and published later. The essay has been influential in Anglo-American philosophy, especially in discussions of social and political philosophy. Berlin distinguishes between two senses of freedom: First, negative freedom, or “freedom from,” which is absence of external interference (absence = negative). Second, positive freedom, or “freedom to,” which is autonomy or mastery over yourself. He argues that each of them has a long history in human thought, and that they are both necessary values.

Almost every moralist in human history has praised freedom. Like happiness and goodness, like nature and reality, the meaning of this term is so vague that there aren’t many interpretations that it seems able to resist. I do not propose to discuss either the history of this word, or the more than two hundred senses of this word, recorded by historians of ideas. I propose to examine no more than two of these senses – but those are central senses, with a great deal of human history behind them...

Negative freedom (freedom from interference)

I am normally said to be free to the degree to which no human being interferes with my activity. Political liberty in this sense is simply the area within which a person can act unobstructed by others. If I am prevented by other persons from doing what I could otherwise do, I am to that degree unfree. And if this area is limited by other men beyond a certain minimum, I can be described as being forced, or, it may be, enslaved. … By being free in this sense I mean not being interfered with by others. The wider the area of non-interference, the wider my freedom…

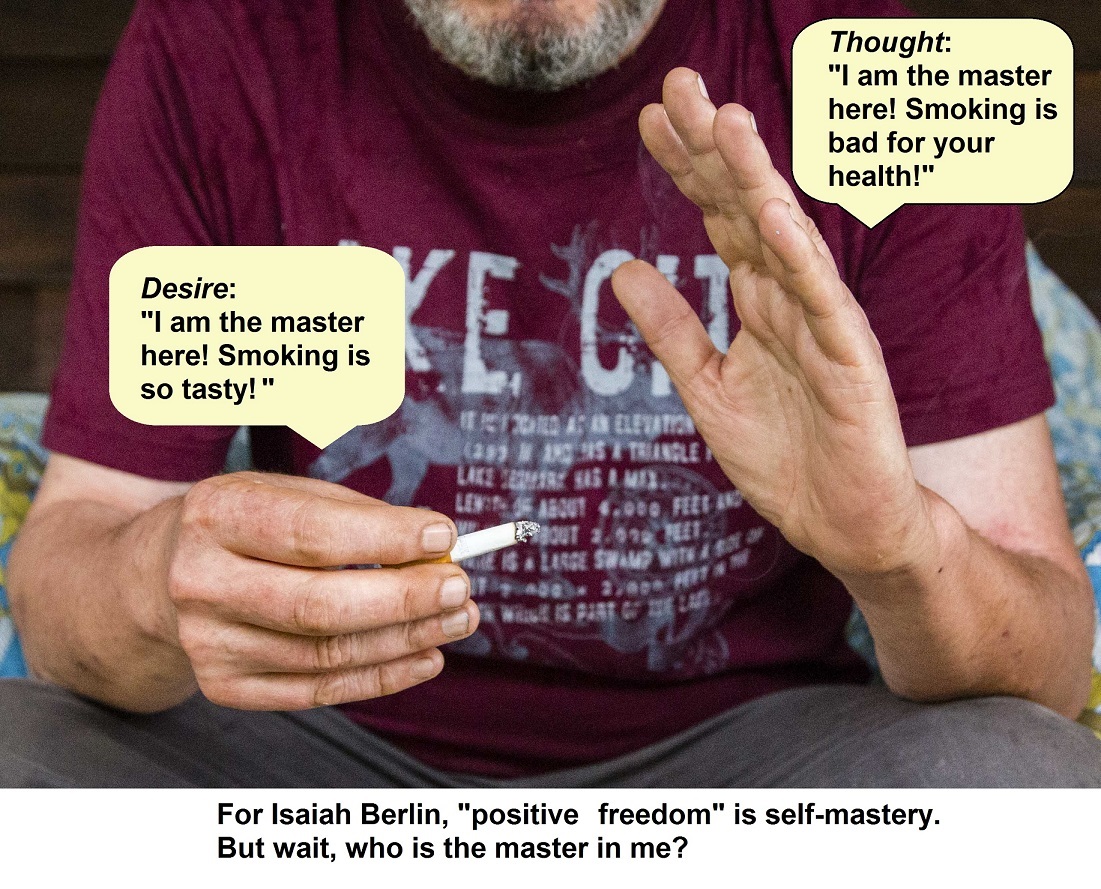

Positive freedom (freedom as self-mastery)

The “positive” sense of the word “liberty” derives from the individual’s wish to be his own master. I wish my life and my decisions to depend on myself, not on external forces of whatever kind. I wish to be the instrument of my own acts of will, not of other men’s. I wish to be a subject, not an object; to be moved by reasons, by conscious purposes which are my own, not by causes which affect me from outside. I wish to be somebody, not nobody; a doer — deciding, not being decided for, self-directed and not acted upon by external nature or by other men as if I were a thing, or an animal, or a slave incapable of playing a human role. In other words, I wish to be somebody who conceives goals and policies of his own and realizes them.

This is at least part of what I mean when I say that I am rational, and that my reason distinguishes me as a human being from the rest of the world. I wish, above all, to be conscious of myself as a thinking, willing, active being, and to bear responsibility for my choices, and to be able to explain them by reference to my own ideas and purposes. I feel free to the degree that I believe this to be true, and I feel enslaved to the degree that I realize that it is not true.

[…]

“I am my own master”; “I am slave to no man”; but may I not be a slave to nature [=natural tendencies]? Or to my own “uncontrolled” passions? … Haven’t people had the experience of liberating themselves from spiritual slavery, or from slavery to nature? And in the process, don’t they become aware of a self which dominates, and on the other hand of something in them which is being dominated? This dominant self is then identified with reason, with my “higher nature,” with the self which calculates and aims at what will satisfy it in the long run, with my “real” or “ideal” or “autonomous” self, or with my self “at its best.” And this self is then contrasted with irrational impulses, uncontrolled desires, my “lower” nature, the pursuit of immediate pleasures, my “empirical” or “heteronomous” self which is swept by every gust of desire and passion, which needs to be rigidly disciplined in order to rise to the full height of its “real” nature.

|

|

|

Like other Stoics, Epictetus believed that many events in life are outside our control. We may plan as much as we want, and we may take as many precautions as we want, but our plans can always be disrupted by unforeseen events like sickness, accidents, chance, and other people’s actions. This means that in most areas of life we do not have full control, and therefore we are not free. There is only one place where we can be, according to Epictetus, fully free: In our inner world – in our decisions, our will, our intentions, our expectations. Nothing can stop me from making a certain decision, nothing can stop me from wanting something or not wanting it. I have complete control over my will and my thoughts.

Like other Stoics, Epictetus believed that many events in life are outside our control. We may plan as much as we want, and we may take as many precautions as we want, but our plans can always be disrupted by unforeseen events like sickness, accidents, chance, and other people’s actions. This means that in most areas of life we do not have full control, and therefore we are not free. There is only one place where we can be, according to Epictetus, fully free: In our inner world – in our decisions, our will, our intentions, our expectations. Nothing can stop me from making a certain decision, nothing can stop me from wanting something or not wanting it. I have complete control over my will and my thoughts.

J. Krishnamurti (1895-1986) was a thinker who never had a university position. Born in India, he was adopted by the Theosophical Society and educated in England, but as a young man he left the society, declaring that “truth has no path.” He therefore rejected connections to any nationality, religion, guru, tradition, dogma. For the rest of his life he spoke with groups and individuals around the world, discussing with them the need for an inner revolution towards freedom.

J. Krishnamurti (1895-1986) was a thinker who never had a university position. Born in India, he was adopted by the Theosophical Society and educated in England, but as a young man he left the society, declaring that “truth has no path.” He therefore rejected connections to any nationality, religion, guru, tradition, dogma. For the rest of his life he spoke with groups and individuals around the world, discussing with them the need for an inner revolution towards freedom.

The following excerpts are adapted from Camus’ book Myth of Sisyphus. According to the book, the world is “absurd” – it offers us no meaning or reason. Life leads nowhere, and death will end it all. This has serious implications about freedom. Freedom means that I can choose a meaningful purpose and achieve it. But if there are no meaningful purposes, and if death will undo everything I choose, then real freedom is impossible. However, the death of freedom opens a door to a new kind of freedom: The “absurd man” (the person who lives in full awareness of the absurd) is free from purposes and values. He is free to create his life without commitment to any meaning.

The following excerpts are adapted from Camus’ book Myth of Sisyphus. According to the book, the world is “absurd” – it offers us no meaning or reason. Life leads nowhere, and death will end it all. This has serious implications about freedom. Freedom means that I can choose a meaningful purpose and achieve it. But if there are no meaningful purposes, and if death will undo everything I choose, then real freedom is impossible. However, the death of freedom opens a door to a new kind of freedom: The “absurd man” (the person who lives in full awareness of the absurd) is free from purposes and values. He is free to create his life without commitment to any meaning.

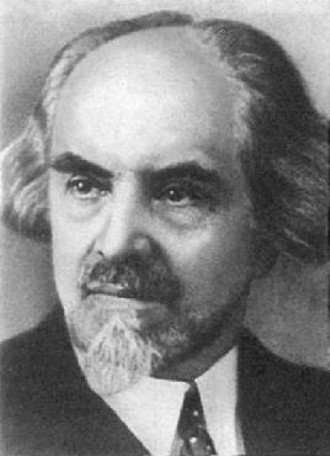

The following text is adapted from Berdyaev’s book Freedom and the Spirit (1927). Berdyaev distinguishes between two kinds of freedom: The freedom to choose your life, which is a limitless freedom that comes from the foundation of human existence; and the freedom that releases you from your lower nature towards the truth. Both of these freedoms, Berdyaev tells us, are problematic. The first freedom can lead to arbitrary decisions, and to slavery to our lower nature. The second freedom invites authority (the church, the state, ourselves) to “free” us from ourselves by force – which contradicts freedom. The solution which Berdyaev offers is a third kind of freedom. This is a spiritual freedom in which truth is not something external to me, but is part of my inner essence – in the form of divine grace. (For Berdyaev, this means that the human being has a human-divine nature, like Christ.) Since truth (God) is part of who I am, it does not force itself on me from the outside. To be free we must therefore cultivate our spirituality and discover our freedom in our inner depth.

The following text is adapted from Berdyaev’s book Freedom and the Spirit (1927). Berdyaev distinguishes between two kinds of freedom: The freedom to choose your life, which is a limitless freedom that comes from the foundation of human existence; and the freedom that releases you from your lower nature towards the truth. Both of these freedoms, Berdyaev tells us, are problematic. The first freedom can lead to arbitrary decisions, and to slavery to our lower nature. The second freedom invites authority (the church, the state, ourselves) to “free” us from ourselves by force – which contradicts freedom. The solution which Berdyaev offers is a third kind of freedom. This is a spiritual freedom in which truth is not something external to me, but is part of my inner essence – in the form of divine grace. (For Berdyaev, this means that the human being has a human-divine nature, like Christ.) Since truth (God) is part of who I am, it does not force itself on me from the outside. To be free we must therefore cultivate our spirituality and discover our freedom in our inner depth.