MARTIN BUBER

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish Austrian-born Israeli philosopher, writer, and an activist of cultural Zionism. He was born in Austria, became a professor in Frankfurt, but after the rise of Nazism left for Israel (then Palestine, under British mandate). He wrote on Hassidism and mysticism, but is best known for his dialogical philosophy, which understands human beings in terms of their relations with each other.

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish Austrian-born Israeli philosopher, writer, and an activist of cultural Zionism. He was born in Austria, became a professor in Frankfurt, but after the rise of Nazism left for Israel (then Palestine, under British mandate). He wrote on Hassidism and mysticism, but is best known for his dialogical philosophy, which understands human beings in terms of their relations with each other.

Buber’s philosophy revolves around relationships – primarily relationship to other persons, but also relationship to trees and animals, relationship to ideas, and relationship to God. For Buber, a human being is not an atom standing by itself, but a person-in-relation. From this point of view, he develops his philosophical ideas about the individual, communication and dialogue, society, education, and God.

| THEMES ON THIS PAGE: | |||||

| 1. I-IT AND I-YOU | 2. THE SPHERE OF THE “BETWEEN” | ||||

| 3. INCLUSION AND DIALOGUE | 4. WITH ANIMALS AND PLANTS | ||||

| 5. WITH IDEAS | 6. WITH GOD | ||||

| 1. I-IT AND I-YOU |

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish Austrian-born Israeli philosopher, writer, and an activist of cultural Zionism. He was born in Austria, became a professor in Frankfurt, but after the rise of Nazism left for Israel (then Palestine, under British mandate). He wrote on Hassidism and mysticism, but is best known for his dialogical philosophy, which understands human beings in terms of their relations with each other.

Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish Austrian-born Israeli philosopher, writer, and an activist of cultural Zionism. He was born in Austria, became a professor in Frankfurt, but after the rise of Nazism left for Israel (then Palestine, under British mandate). He wrote on Hassidism and mysticism, but is best known for his dialogical philosophy, which understands human beings in terms of their relations with each other.

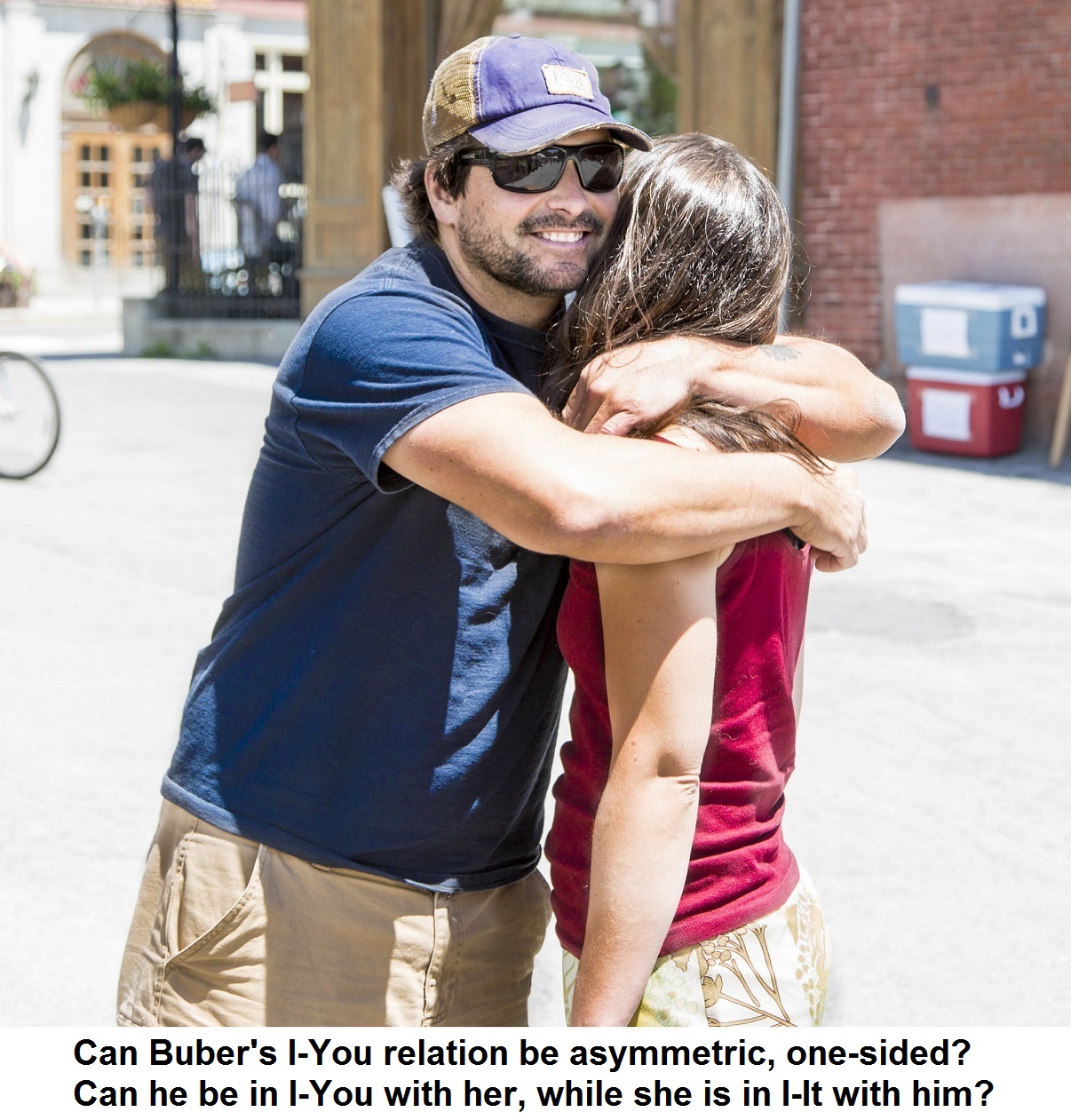

Buber’s philosophy revolves around relationships – primarily relationship to other persons, but also relationship to trees and animals, relationship to ideas, and relationship to God. For Buber, a human being is not an atom standing by itself, but a person-in-relation. From this point of view, he develops his philosophical ideas about the individual, communication and dialogue, society, education, and God. Buber distinguishes between two fundamental kinds of relationships: I-It relations and I-Thou (I-You) relations. In I-It relations, I regard somebody as an object, as an ”it.” The other is an object for me (object of thought, object of interest or desire, object of experience, of manipulation, of pity or concern, etc.). In contrast, in I-You relations, I relate to somebody as a You. I am in togetherness with him – fully, with my whole being, without objectification or boundaries. And since I am defined by my relationships, I am different when I am in I-You and when I am in I-It.

I-It and I-You

Buber distinguishes between two fundamental kinds of relationships: I-It relations and I-Thou (I-You) relations. In I-It relations, I regard somebody as an object, as an ”it.” The other is an object for me (object of thought, object of interest, object of experience, of manipulation, of pity, etc.). In contrast, in I-Thou relations, I relate to somebody as a You. I am in togetherness with him – fully, with my whole being, without objectifications or boundaries. And since I am defined by my relationships, I am different when I am in I-You and when I am in I-It.

The world is two-fold for man, according to his two-fold attitude. A man’s attitude is two-fold according to two words which he can speak. The basic words are not single words, but words in pairs.

One basic word is I-You.

The other basic word is I-It – but this basic word doesn’t change when the It is a person, he or she.

Therefore, man’s I is also two-fold. Because the I of I-You is different from the I of I-It.

[…]

The basic word I-You can only be spoken with one’s whole being. The basic word of I-It can never be spoken with one’s whole being.

There is no I by itself, but only the I of I-You and the I of the I-It.

There is no I by itself, but only the I of I-You and the I of the I-It.

[…]

I perceive something. I feel something. I imagine something. I want something. I sense something. I think something. […] All this is the basis of the domain of It. But the domain of You has another basis.

Whoever says You does not have something as his object. Because where there is “something” there is also another something. Every It borders on other Its. It is only because it borders on other Its. But where there is You, there is no something. You has no borders.

Whoever says You does not have something. He has nothing. But he stands in relation.

[…]

When I encounter a human being as my You and I say to him the basic word I-You, then he is not a thing among things, and he doesn’t consist of things.

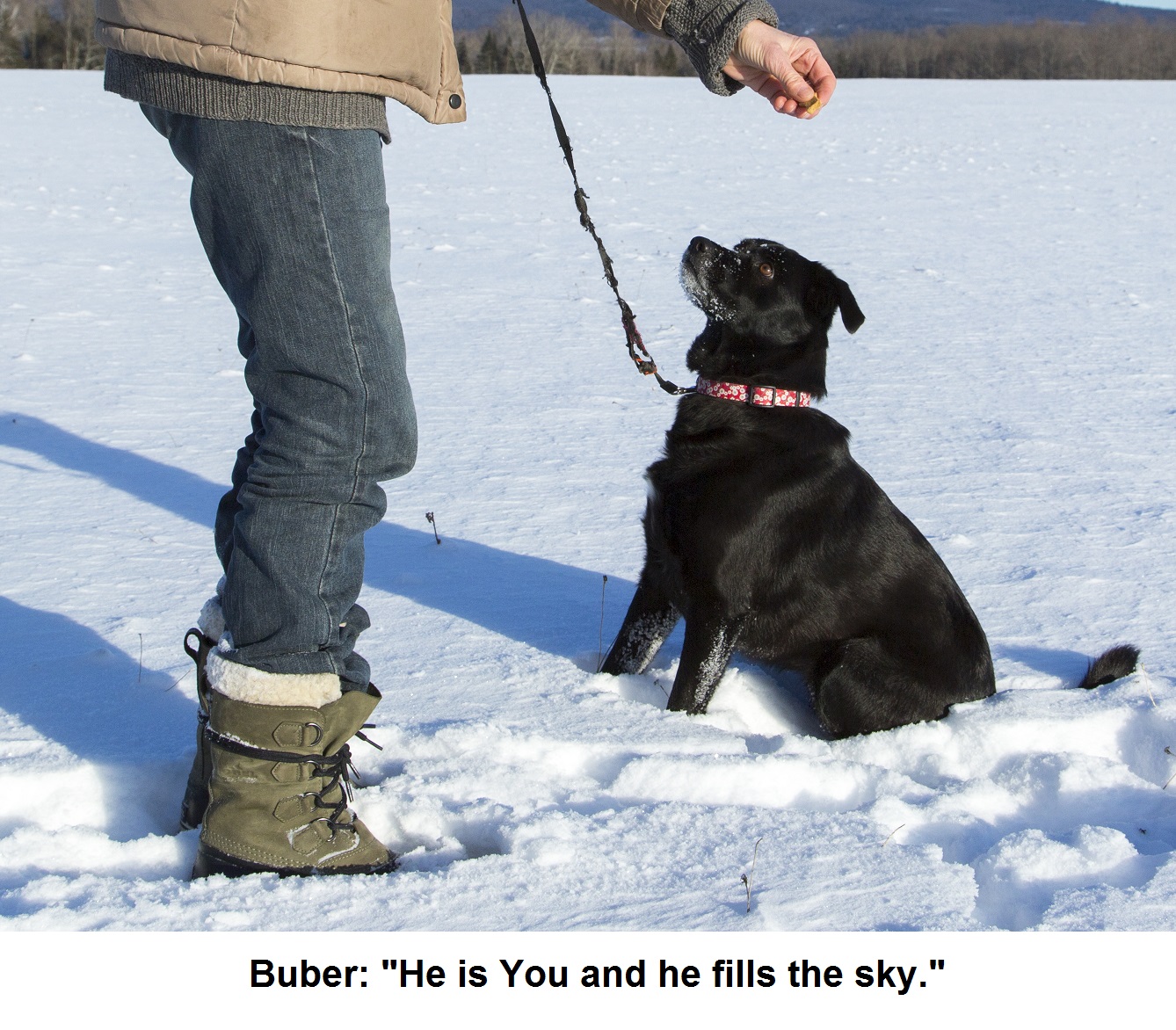

He is no longer He or She, limited by other Hes and Shes, a dot in the world-grid of space and time. Nor is he a condition that can be experienced and described, a collection of certain qualities. Without neighbors and without division, he is You and he fills the sky. It’s not as if there is nothing except for him, but rather everything lives in his light.

Just as a melody is not made of tones, and a poem is not made of words, and a statue is not made of lines (I must pull and tear it in order to turn unity into multiplicity), the same is with a You. I can abstract from him the color of his hair, or the color of his speech, or the color of his kindness. I have to do this again and again, but immediately he is no longer You.

Just as a melody is not made of tones, and a poem is not made of words, and a statue is not made of lines (I must pull and tear it in order to turn unity into multiplicity), the same is with a You. I can abstract from him the color of his hair, or the color of his speech, or the color of his kindness. I have to do this again and again, but immediately he is no longer You.

[…]

I do not experience the person I call You. But I stand in relation to him, in the sacred basic word of You. Only when I step out of this, I experience him again. Experience is a distance from You.

[…]

The relation to the You is not mediated by anything. Nothing conceptual stands between I and You, no prior knowledge, no imagination. And memory itself is changed as it goes from particularity to wholeness. No purpose intervenes between I and You, no greed and no anticipation.

[…]

Without It a human cannot live. But whoever lives only with It is not human.

| 2. THE SPHERE OF THE "BETWEEN" |

A relationship, for Buber, does not include only two independent individuals. When Peter and Mary relate to each other in an authentic way, their encounter has more reality than Peter plus Mary. There is, most importantly, a “between” between them, and this “between” is not part of Mary and not part of Peter.

A relationship, for Buber, does not include only two independent individuals. When Peter and Mary relate to each other in an authentic way, their encounter has more reality than Peter plus Mary. There is, most importantly, a “between” between them, and this “between” is not part of Mary and not part of Peter.

The following passage is slightly adapted from the last section of Buber’s series of lectures “What is Man?” (1938), which appeared in his book Between Man and Man (1947).

The fundamental fact of human existence is a human being with a human being. What is peculiarly characteristic of the human world is, above all, that something takes place between one human being and another, and nothing like it can be found anywhere else in nature. Language is only a sign of it and an instrument for it. All the achievements of the spirit have been inspired by it. This fundamental fact makes a human being a human being, but it does not only develop, it also decays and declines. It is based on one human being turning to another as another – as this particular other human being – in order to communicate with him in a sphere which is common to both of them, but which goes beyond the specific sphere of each one of them. I call this sphere, which is established with the existence of a human being as a human being, but which is conceptually still not well-understood, the sphere of “between.” Although it can be realized in very different degrees, it is a primal category of human reality. This is where the genuine third alternative [=to individualism and collectivism] must begin.

We recognize the idea of the “between” when we no longer localize the relation between human beings inside individual souls (as is customary), or in a general world that includes and determines them, but rather BETWEEN them.

“Between” is not a secondary construction, but the real place that contains what happens between humans. […] In a real conversation, in a real lesson, in a real embrace that is not just a habit, in a real duel that is not just a game – in all these, what is essential does not take place in each of the participants, or in a neutral world which includes both of them and all other things. Rather, it takes place in a dimension which is accessible only to them both.

When something happens to me – this fact can be exactly divided between what happens in the world and what happens in the soul, between an “outer” event and an “inner” experience. In contrast, if I and another human meet each other, if we “happen” to one another (to use a forced expression), the sum does not exactly divide. Something remains somewhere, where the souls end and the world does not yet begin, and this remainder is what is essential. This fact can be found even in the smallest momentary events which hardly enter our consciousness.

In a crowd in an air-raid bunker, the eyes of two strangers suddenly meet for a second in a surmising mutuality between unrelated people. When the “All Clear” siren is heard, this moment of mutuality is forgotten. And yet, it did happen, in a domain which existed only for that moment.

In the darkened opera-house, a relation that is hardly perceptible can happen between two people in the audience who do not know each other, and who are listening in the same purity and with the same intensity to the music of Mozart – and yet, it is a relation of fundamental dialogue, which disappears before the lights are turned on again.

When we try to understand such momentary and yet consistent events, we must be careful not to introduce motives of feelings. What happens here cannot be understood with psychological concepts. It is something ontic. … The dialogical situation can be properly understood only in an ontological way. But it cannot be understood on the basis of the ontic of personal existence, or on the basis of two personal existences, but on the basis of what exists between them, and transcends them both. […] On the far side of the subjective, on this side of the objective, on the narrow ridge where I and You meet, there is the realm of “between.”

| 3. INCLUSION AND DIALOGUE |

A central concept for Buber is that of dialogue. Indeed, his philosophy is sometimes described as dialogical philosophy. However, a true dialogue is not simply an exchange of words. It can take place without words, and it can be absent in a conversation. Buber uses the notion of “inclusion” to explain the meaning of dialogue. In inclusion I include your experiences in my own world, and I experience the event from your side.

A central concept for Buber is that of dialogue. Indeed, his philosophy is sometimes described as dialogical philosophy. However, a true dialogue is not simply an exchange of words. It can take place without words, and it can be absent in a conversation. Buber uses the notion of “inclusion” to explain the meaning of dialogue. In inclusion I include your experiences in my own world, and I experience the event from your side.

The following text is slightly adapted from Buber’s lecture “Education” which he gave in 1926 (published in Buber’s book Between Man and Man). In this lecture Buber explains that education is based on a true dialogue between the teacher and the student, and that it is aimed at creating a dialogical attitude in the student. The passage below explains what dialogue is.

A man hits another person, who remains quite still. Then, let us assume that the attacker suddenly receives in his soul the blow which he gives – the same blow. He receives it just as the person who does not move receives it. For a short while, he experiences the situation from the other side. Reality imposes itself on him. What will he do? Either he will suffocate the voice of his soul, or his violent impulse will be changed and reversed.

A man caresses a woman, and she lets herself be caressed. Then, let us assume that he feels the touch from both sides — both from his side with his hand, and from the woman’s side on her skin. The two-fold nature of the act, as a movement that takes place between two persons, excites a deep enjoyment in his heart and moves it. If he does not make his heart deaf, he will have to — not reject the enjoyment, but love.

I do not mean at all that the man who had such an experience would, from now on, have this two-sided sensation in every such meeting. That would perhaps destroy his instinct. But the extreme experience makes the other person present to him forever. A transfusion has happened, and afterwards, he will not find it sufficient or tolerable to have a mere sense of subjectivity. […]

It would be wrong to identify what I mean here with the familiar (but not very significant) term “empathy.” Empathy means, if anything, to glide with your feeling over the dynamic structure of an object – a pillar, or a crystal, or the branch of a tree, or even of an animal or a person – and to trace it from the inside, so to speak, and in this way to understand the formation and motion of the object through the perceptions of your own muscles. It means to “transpose” yourself from here to over there and in there. Thus, it means to exclude your own concreteness, to extinguish your actual situation, to absorb in pure aestheticism the reality in which you participate.

INCLUSION is the opposite of this. It means to extend your own concreteness, to fulfill the actual situation of life, to make completely present the reality in which you participate. Its elements are, first, a relation (no matter which kind) between two persons; second, an event that is experienced by both of them in common, in which at least one of them participates actively; and, third, that this person lives through the common event from the perspective of the other person, without losing anything of the experienced reality of his own actions. A relation between persons that is characterized, in a higher or lower degree, by the element of inclusion may be called a DIALOGICAL RELATION.

A dialogical relation can also appear in an authentic conversation, but the relation itself is not composed of conversation. A silence shared by two persons can also be a dialogue, and their dialogical life continues even when they are separated in space, as the continual potential presence of the one person to the other, as an unexpressed contact. On the other hand, every conversation receives its authenticity only from the awareness of inclusion — even if this awareness is only an abstract “acknowledgement” of the actual being of the partner in the conversation. But this acknowledgement can be real and effective only when it comes from an experience of inclusion, an experience of the other side.

[…] The element of inclusion, clarified above, is the same as that which constitutes the relationship in education.

The relationship in education is one of pure dialogue.

| 4. WITH ANIMALS AND PLANTS |

For Buber, the special I-You relation is found not only between human beings. A person can be in I-You with a dog, and even with a tree. I-You is a basic relation that does not require words, does not require thoughts or even consciousness. Of course, in the case of human beings it may express itself in words, but words are not necessary. I-You means that there is “something” between me and you which is more than just you and just me.

For Buber, the special I-You relation is found not only between human beings. A person can be in I-You with a dog, and even with a tree. I-You is a basic relation that does not require words, does not require thoughts or even consciousness. Of course, in the case of human beings it may express itself in words, but words are not necessary. I-You means that there is “something” between me and you which is more than just you and just me.

Some of Buber’s readers found this idea difficult to understand. See below his attempt to explain it in the “Afterwards” which he wrote 25 years after the original book I and Thou.

From Buber’s book I and Thou (1923), First Part:

There are three spheres in which the world of relations arises.

The first: Life with nature. Here the relation vibrates in the dark and remains below language. The creatures live and move in front of us, but they are unable to come to us, and the You we say to them gets stuck on the threshold of language.

The second sphere: Life with people. Here the relation is manifest, and it enters language. We can give and receive the You.

The third sphere: Life with intelligible beings [ideas, poems, works of art, etc.].

[…]

I contemplate a tree.

I can accept it as an image: A rigid pillar in a flood of light, with a delicate blue and silver background.

I can feel it as movement: The flowing veins around the strong, striving core, the sucking of the roots, the breathing of the leaves, the infinite interaction with earth and air – and the growing itself in the darkness. I can classify the tree as belonging to a given species, and regard it as an instance of it, and study its structure and its way of life.

I can ignore the tree’s uniqueness and shape, so that I recognize it only as an expression of general laws [of nature] – those laws that interact with each other and balance each other, or those laws according to which the elements mix and separate.

I can dissolve the tree into a number, into a pure relation between numbers, and eternalize it.

When I do all this, the tree remains my object, and it occupies an interval of space and time, and it belongs to a certain kind and certain conditions.

But it can also happen, if I have both will and grace, that when I contemplate the tree, I am pulled into a relation to it, and the tree stops being an It. The power of exclusiveness has captured me.

This does not require me to give up my ways of contemplating. There is nothing that I must stop seeing in order to see, and there is no knowledge that I must forget. Rather, everything is included – image and movement, species and instance, law and number – and everything is united without separation. Whatever belongs to the tree is included: Its shape and its mechanics, its colors and its chemistry, its interaction with the elements and its interaction with the starts – all this is present in a single whole.

The tree is not an experience, not a play of my imagination, not an aspect of a mood. It confronts me bodily, and it has to deal with me as I must deal with it – only differently.

The tree is not an experience, not a play of my imagination, not an aspect of a mood. It confronts me bodily, and it has to deal with me as I must deal with it – only differently.

One should not try to dilute the meaning of the relation. Relation is mutual.

Does the tree have consciousness, similar to our own? I have no experience of that. But do you wish to divide again the indivisible, thinking that you succeeded in your own case? What I encounter is neither the soul of a tree, nor a dryad [=nymph], but the tree itself.

From the “Afterward” which Buber added to his book in 1957. Here Buber explains that we may have a relationship with a tree even though it is not a relationship of actions and reactions. It is a togetherness of being.

Animals are not two-sided like humans. The duality of the basic words I-You and I-It is foreign to them, although they can turn toward another being and also contemplate objects. We may say that in animals, the two-sidedness is latent [sleeping, potential, hidden]. From the perspective of our ability to say You to animals, we may call this sphere the threshold of mutuality.

This is very different from those domains of nature which lack the spontaneity that we share with animals. It is part of our concept of the plant that a plant cannot react to our actions on it, that it cannot “reply.” Yet, this does not mean that we find no mutual relation at all in this sphere. We find here not the bodily action of an individual being, but a mutuality of being itself – a mutual relation that has nothing except being. The living wholeness and unity of a tree escapes the eye (however sharp) of anybody who just investigates [objectively], while it is visible to those who say You. This wholeness is present when THEY are present: They grant the tree the opportunity to show it, and now the tree which has being shows it.

Our habits of thought make it difficult for us to see that in such cases, something is awakened by our attitude, and it flashes towards us from the tree which has being. What matters in this sphere is that we should open-mindedly do justice to the actuality that opens up before us.

| 5. WITH IDEAS |

Buber maintains that we can have I-You relationship in three spheres: relationships with natural things such as animals and plants, relationships with other human beings, and relationships with “intelligible beings” (also translated as “spiritual beings”): ideas, works of art, poems, etc. In the following passages Buber explains that these beings are not just abstract things but realities that interact with us. In other words, they are not an “It” but a “You.”

Buber maintains that we can have I-You relationship in three spheres: relationships with natural things such as animals and plants, relationships with other human beings, and relationships with “intelligible beings” (also translated as “spiritual beings”): ideas, works of art, poems, etc. In the following passages Buber explains that these beings are not just abstract things but realities that interact with us. In other words, they are not an “It” but a “You.”

From Buber’s book I and Thou (1923), First Part:

The third sphere of relations: Life with intelligible beings. Here the relation is covered in a cloud, but it reveals itself. It lacks language but it creates it. We hear no You, yet we feel that we are addressed. We answer – by creating, thinking, acting. With our being we speak the basic word [“You”], unable to say “You” with our mouth.

But how can we bring into the world the basic word [“You”] what lies outside language?

In every sphere, through everything that becomes present to us, we look towards the edge of the eternal You [= God]. In each being we perceive a breath of it. In every You we address the eternal You, in every sphere in its own way.

In the “Afterward” which Buber added in 1957 to his book I and Thou, Buber explains how we may have a relationship with an idea, a work of art, etc. The simplest example is when we can relate in our mind to a creator who died, and we feel his voice speaking in us. One might think that this is only a metaphor, but Buber takes it seriously.

Let those who ask about the realm of intelligible beings remember one of the traditional sayings of a master who died thousands of years ago. Let them try, as best as they can, to receive this saying with their ears – as if the speaker had said it in their presence, addressing them. For this purpose, they must turn with their whole being toward the speaker, who is not available now, but who spoke the words that are still available. Thus, they must adopt toward the master who is dead-but-living the attitude which I call You-speech. If they succeed, they will hear a voice, perhaps not very clearly at first, that is the same voice that speaks to them through other true sayings of the same master. Now they will no longer be able to do what they did while they treated the saying as an object: They will not be able to separate content from rhythm. They will receive the indivisible wholeness of something spoken.

But in this example we are still dealing with a person and with how he appears through his words. What I have in mind, however, is not limited to the continued presence of some personal existence in words. […]

Spirit becomes word, spirit becomes form. Anybody has been touched by the spirit and did not shut himself off, knows to some extent this fundamental fact: Neither word nor form germinates and grows in the human world if its seed has not been put in the ground. These are not encounters with Platonic ideas, but with the spirit that blows around us and inspires us. I recall the strange confession of Nietzsche, who described the process of inspiration by saying that one accepts without asking who gives. This may be so – one does not ask, but one gives thanks.

Those who know the spirit’s breath do wrong if they try to gain power over the spirit, or to determine its nature. And they are also unfaithful if they credit the gift to themselves.

[…] One could ask at this point whether we have any right to speak about a “reply” or “address” that comes from outside the sphere of spontaneity and consciousness, as if it was similar to a reply or address in the human world in which we live.

[…] To understand this, we must sometimes step out of our habit of thought, but not out of the basic norms of human thought about what is actual. Both in the domain of nature and in the domain of spirit – the spirit that continues living in words and works, and the spirit that strives to become words and works – what acts on us may be understood as the action of what has being.

| 6. WITH GOD |

For Buber, God too should be understood as a You – as the Eternal You. God is not an “It” – he is not a thing, an objective fact, a principle, an energy, but rather a “someone” whom the individual can encounter only in a personal dialogue. A real dialogue is always in the present, always new, free, and personal. This means that religious institutions, dogmas, and authorities are not the real thing. They may be based on true moments from the past, but in themselves they are just human structures. Indeed, Buber, who felt close to Judaism, always emphasized the spiritual movement in the heart of individuals, while downplaying the religious laws and institutions.

God, the Eternal You, is the topic of the third part of Buber’s book I and Thou. (The first part is about relations between individuals, the second part is about society, and the third about God.) The following is the first passage of this third part.

The extended lines of relationships intersect in the eternal You.

Every particular You is a glimpse of the eternal You. Through every particular You, this basic word addresses the eternal You. This mediation of the You of all beings gives birth to the fulfillment of our relationships to them – or to the lack of fulfillment. The innate You is realized in each relation without ever being perfected. It reaches perfection only in the direct relationship to the You, which by its nature cannot become an It.

People have addressed their eternal You with many names. When they sang about what they had named, they still meant You. The first myths were hymns of praise. Then the name entered the language of It. People felt forced more and more to think and talk about their eternal You as if it was an It. But all the names of God remained holy – because they have been used not only to speak ABOUT God but also to speak TO him.

Some people deny any legitimate use of the word “God” because it has been misused so much. Certainly, it is the most burdened of all human words. But precisely for that reason, it is the most imperishable and unavoidable word. And how important is all this mistaken talk about God’s nature and works, compared with the one truth which everybody who has addressed God really meant? Because anyone who pronounces the word “God” and really means You, addresses (whatever he imagines) the true You of his life. This is the You who cannot be limited by any other You, and to whom he stands in a relationship that includes all Yous.

But whoever hates this name, and imagines himself to be godless, in fact addresses God when, with his whole being, he addresses the You of his life that cannot be limited by any other You.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.