|

An issue for reflection

WHAT IS BEAUTY?

|

|

|

|

- Look at my new car! It’s beautiful, don’t you think?

- Well… Beauty is a subjective perception.

- Subjective perception? When you and I look at my car, do we perceive different things?

- Obviously.

- What do I perceive when I look at it and see it as beautiful?

- You perceive, for example, that it is new and shiny.

- Are you saying that “beautiful” means the same as “new and shiny”?

- No, of course not. Beautiful is beautiful and shiny is shiny. My point is this: When you say “It’s beautiful” you are really saying “I personally like it.”

- Really? Is “beautiful” the same as “I like it”? I personally like your car, I like the way it looks – wild and nasty and powerful, but it is really quite ugly.

- Alright, alright. So what is YOUR answer? What do you see in your new car?

- Beauty of course.

- Yes, yes, but what is beauty?

|

|

|

|

April Week 1 quotation

PLOTINUS

|

|

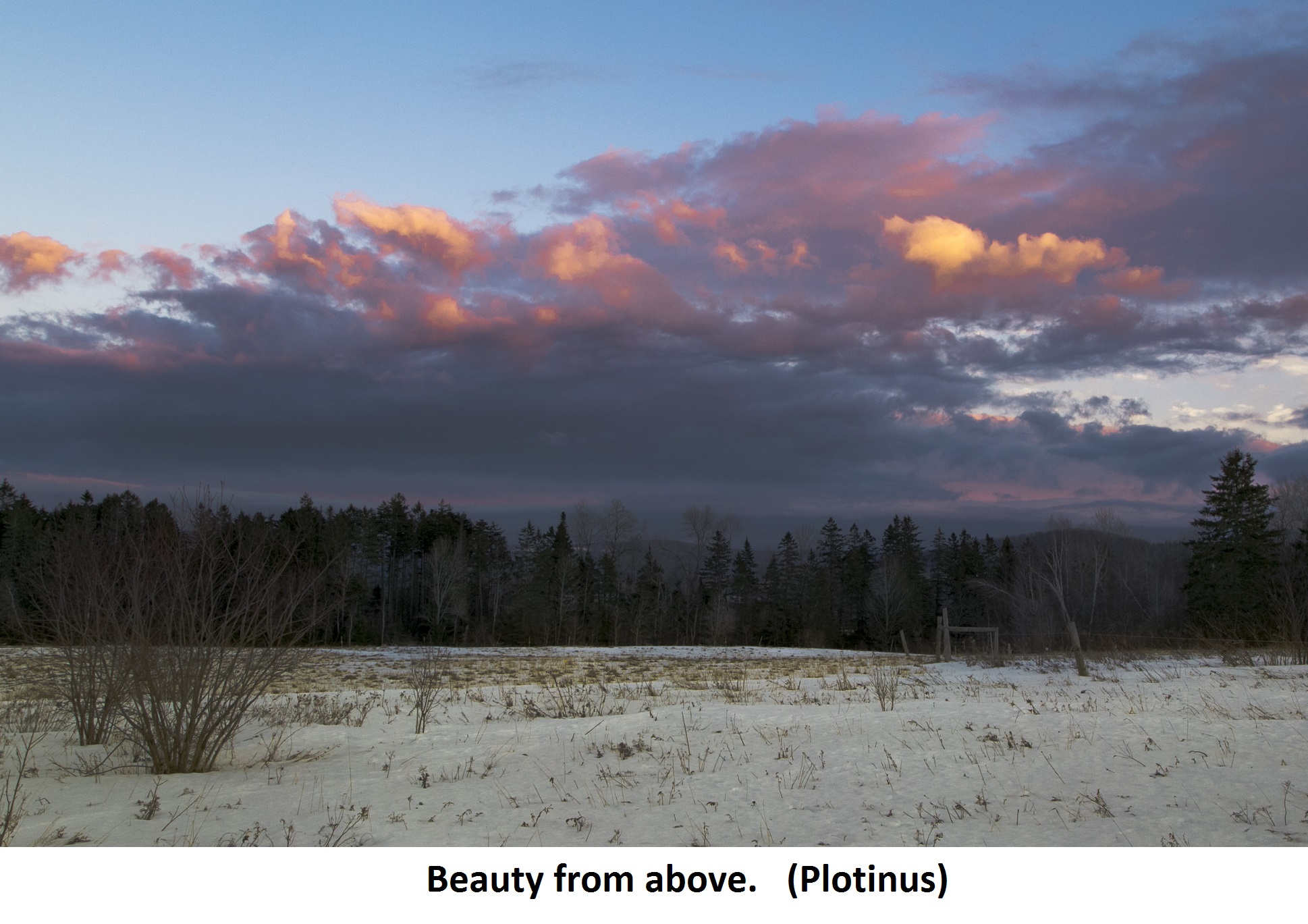

Beauty comes from above

Plotinus (204-270 AD) was a major Neo-Platonist philosopher who lived in late antiquity, mostly in Rome. Inspired by Plato, but going beyond Plato, he regarded reality as composed of several levels: Plotinus (204-270 AD) was a major Neo-Platonist philosopher who lived in late antiquity, mostly in Rome. Inspired by Plato, but going beyond Plato, he regarded reality as composed of several levels:

The One, the Intellect, the Soul.

The highest level of being is The One (the Good). The Intellect emanates from The One. And the Soul emanates from the Intellect. The material world is the lowest, imperfect level. For Plotinus, this was not just an abstract theory, but a way of life: The philosopher aspires to rise to the highest level of being by living a life of purity and virtue, meditation, and the study of philosophy. The final goal is a mystical union with the One.

Very little is known about Plotinus’ early life. His student Porphyry wrote about him that he “seemed ashamed of being in the body. This feeling was so deeply rooted, that it was impossible to convince him to tell about his ancestry, his parents, or his birthplace.” At the age of 27 Plotinus went to Alexandria to study philosophy, then to Persia in pursuit of knowledge. At the age of 40 he came to Rome, where, until the end of his life, he taught a circle of followers, among them also women and important public figures. Historical accounts describe him as an extraordinary person of wisdom, composure, and justice. His teachings were collected by his student Porphyry and compiled in the book Enneads.

The following are excerpts from Plotinus’ essay “Beauty” (First Ennead, tractate 6). Plotinus explains here that the beauty we perceive in the material world is only a reflection of a higher, non-material beauty. The source of the higher beauty is The One, and this beauty emanates down to the Intellect, and from there down to the Soul, where we experience it. (The lower part of the Soul is made of individual human souls.) These ideas are inspired by Plato’s theory of love (in the symposium), as Plotinus himself acknowledges.

Several ideas are interesting in this text, aside from Plotinus' metaphysics: that there are higher and lower kinds of beauty, that sublime beauty can awaken in us the sublime part of ourselves, and that you need to connect to your inner beauty in order to appreciate beauty.

Beauty appears mainly through seeing, but there is also beauty for hearing, as in certain combinations of words, and in all kind of music, since melodies and cadences are beautiful. And if we rise above the world of senses to a higher level, we will see beauty in the conduct of life, in actions, in the personality, in intellectual pursuits; and there is also the beauty of virtues. But whether above these kinds of beauty there is a higher beauty, this we will discover in this investigation.

2. Let us, then, go back to the source, and find the principle that gives beauty to material things. Undoubtedly, this principle exists. It is something which is perceived at a first glance, and which the soul recognizes like from an ancient knowledge, and the soul welcomes it eagerly, and unites with it.

But when the soul meets something ugly, it quickly shrinks within itself, rejects that thing, turns away from it, resenting its discordant nature.

This is because the soul, by its very nature, through its affiliation with the noblest levels in the hierarchy of Being, when it sees something that has affinity to itself, or any trace of that affinity, is immediately thrilled with delight, and it enters into itself, and thus awakens its own nature and remembers all its affinities.

[...]

4. But there are beauties that are more basic and high than these material beauties. In the world of the senses we no longer know them, but the soul, which does not rely on sense-organs, sees them and announces them. We must ascend to the vision of these beauties, and leave the senses in their low place.

[…]

Such a vision is only for those who see with the sight of the Soul. And when they experience this vision, they rejoice, and they are filled with joy and with agitation that is deeper than anything else, because now they are moving in the realm of truth. This is the spirit which beauty always inspires, wonderment and a delicious agitation, longing and love and a delightful trembling.

6. […] And Beauty, this beauty which is also The Good, is the First. From this First comes The Intellect, which is the first manifestation of Beauty. Through the Intellect, the Soul is beautiful. The beauty of lower things – for example, of actions and pursuits – is shaped by the Soul, which is the author of the beauty that is found in the world of senses. Because the Soul, which is a divine thing, and which is a fragment (so to speak) of Beauty, makes things beautiful, as much as they can be, by shaping and molding them.

7. Therefore we must ascend again towards the Good, which is what every soul desires. Anyone who has seen it, knows what I mean when I say that it is beautiful.

|

|

|

April Week 2 quotation

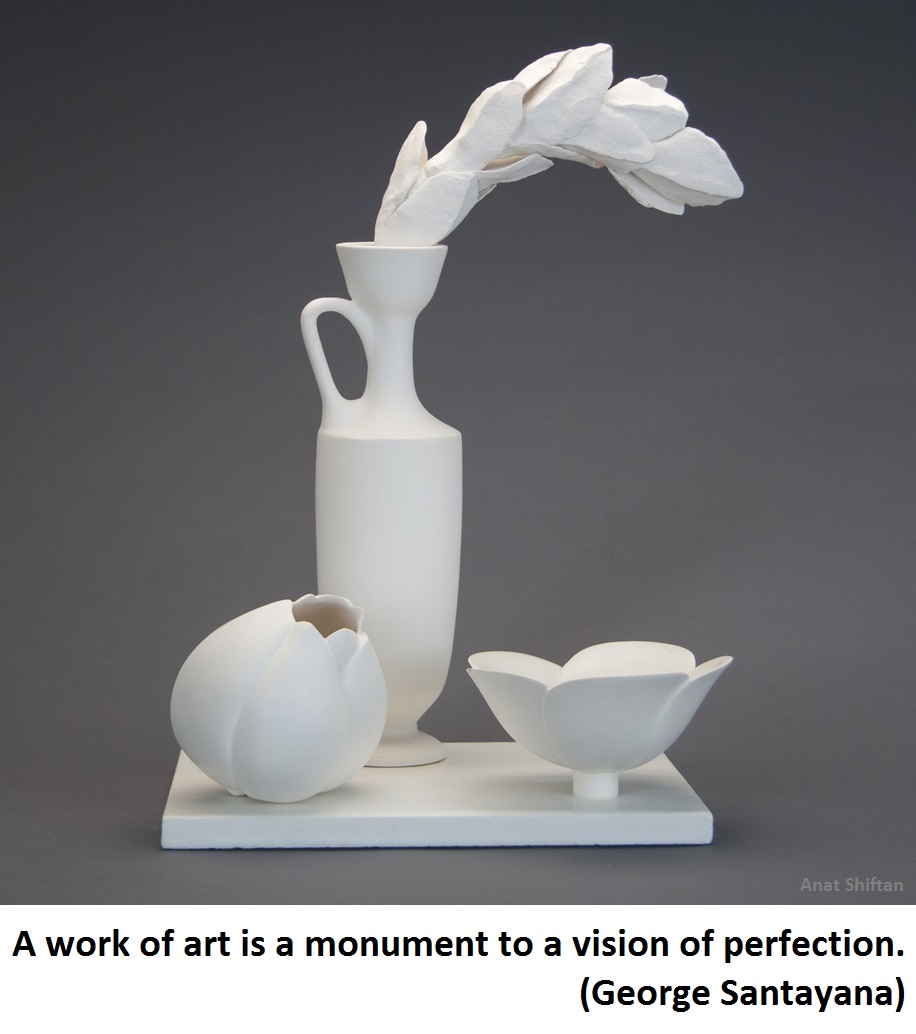

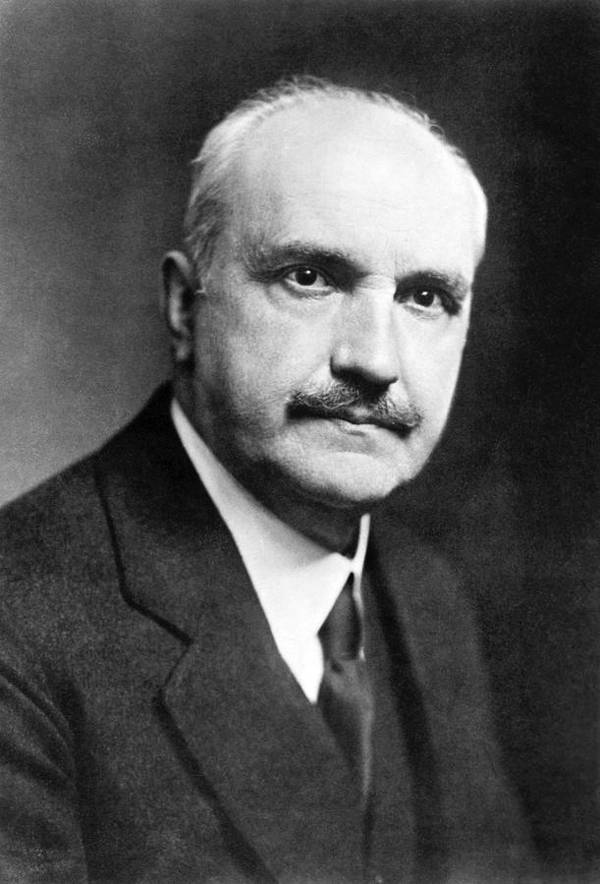

GEORGE SANTAYANA

|

|

Beauty as a vision of perfection

George Santayana (1863-1952) was a Spanish-born philosopher, poet and novelist. He was one of several prominent American philosophers of the 19th and early 20th centuries (together with Emerson, James, Peirce, Dewey, Royce). As a child he moved with his parents from Spain to Boston, where he later went to Harvard, received his doctorate, and then became a philosophy professor. During his years at Harvard he was active in many philosophical and literary activities. At the age of 48 he resigned from the university and returned to Europe, where he lived for the rest of his life and refused all academic positions. George Santayana (1863-1952) was a Spanish-born philosopher, poet and novelist. He was one of several prominent American philosophers of the 19th and early 20th centuries (together with Emerson, James, Peirce, Dewey, Royce). As a child he moved with his parents from Spain to Boston, where he later went to Harvard, received his doctorate, and then became a philosophy professor. During his years at Harvard he was active in many philosophical and literary activities. At the age of 48 he resigned from the university and returned to Europe, where he lived for the rest of his life and refused all academic positions.

The following passages are adapted from Santayana’s first philosophy book The Sense of Beauty (1896). In this book Santayana explains that beauty gives us a sense of perfection. Beauty is not an absolute metaphysical quality – it depends on human perception and on human consciousness. But given the similarity between human minds, the sense of beauty is generally similar for most of us. Beauty is a testimony that the world can harmonize with our inner ideals.

From Chapter 11

Beauty is a value, not a perception of a fact – it is an emotion, a feeling of wanting and appreciating. An object cannot be beautiful if it can give pleasure to nobody. A beauty to which all people are always indifferent is a contradiction.

From Chapter 65

Only the good of life enters into the texture of the beautiful. What charms us in the comic, what moves us in the sublime and touches us in the pathetic, is a glimpse of some good. Imperfection has value only as a potential perfection. […] In the happiest and most prosperous moments of humanity, when the mind and the world were joined into a brief embrace, natural beauty has been best perceived, and art has won its triumphs. But it sometimes happens, in less favorable moments, that the soul is enslaved to its works, and it loses its power of idealization and hope.

We need to clarify our ideals, and to animate our vision of perfection. […] Our consciousness of the ideal becomes clearer when we advance in virtue, and when our faculties work with more vigor and certainty. When the vital harmony is complete, when the act is pure, our faith in perfection becomes vision. A person is unhappy indeed, if in all his life he has had no glimpse of perfection, if in the ecstasy of love, or in the delight of contemplation, he has never been able to say: “It is attained.” Such moments of inspiration are the source of the arts, whose higher function is to renew those moments.

A work of art is indeed a monument to such a moment, the memorial to such a vision. And its charm depends on its power to take us from the distractions of common life to the joy of a more natural and perfect activity.

From Chapter 66

There is a broad foundation of similarity in human nature, so that we live in a common world, and have an art and a religion in common. It is inevitable that our ideal would be the same within these limits (just as it would be different beyond them). And as long as we recognize ourselves individually as persons, or collectively as human, we must recognize also our inner ideal, whose realization would be perfection for us. That ideal cannot be destroyed unless we ourselves die. An absolute perfection, independent of human nature and its variations, may interest the metaphysician; but the artist and the human being will be satisfied with a perfection that is connected to human consciousness, since it is both the natural vision of the imagination, and the rational goal of the will.

From Chapter 67

This satisfaction of our reason, due to the harmony between our nature and our experience, is partly realized already: The sense of beauty is its realization. When our senses and imagination find what they desire, when the correspondence between the world and the mind is perfect, then perception is pleasure, and existence needs no apology. The duality which creates conflict disappears. There is no internal standard that is different from the external fact to which it may be compared. A unification of this kind is the goal of our intelligence and of our affection, no less than of our aesthetic sense […] Beauty therefore seems to be the clearest manifestation of perfection, and the best evidence of its possibility. If perfection is (as it should be) the ultimate justification of being, then we may understand the ground of the moral dignity of beauty. Beauty is a promise of the possible conformity between the soul and nature, and consequently it is the basis of our faith in the supremacy of the good.

|

|

|

. ......

|

|

April Week 3 quotation

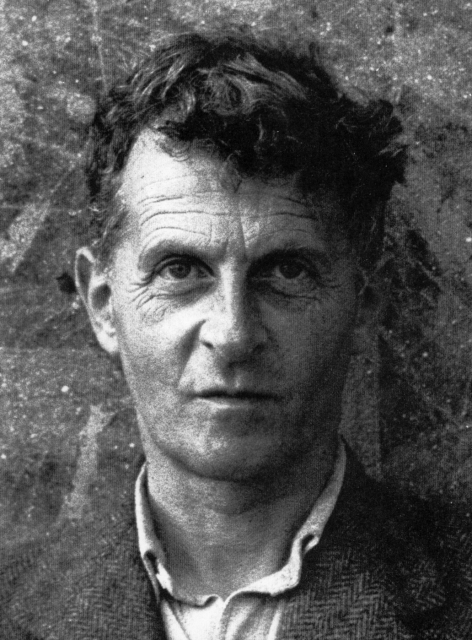

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN

|

|

What kind of word is “beautiful”? An interjection.

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) was an Austrian-born philosopher who wrote and taught mainly at Cambridge University in England. He was one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, who helped make philosophy of language central to the field. Wittgenstein was born in Vienna to a very rich family, mostly Jewish. As an Austrian soldier in World War I, he wrote his first book Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which he completed in prison camp. The very short book was published when he was 22-years-old, and made him famous in the field of philosophy. Afterwards he left academia and worked as a school-teacher in a remote Austrian village, and as a gardener. He returned in 1929 to Cambridge to develop a different kind of philosophical approach, often called his “later philosophy.” This included his famous book Philosophical Investigations (published after his death in 1953), as well as the text below. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) was an Austrian-born philosopher who wrote and taught mainly at Cambridge University in England. He was one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, who helped make philosophy of language central to the field. Wittgenstein was born in Vienna to a very rich family, mostly Jewish. As an Austrian soldier in World War I, he wrote his first book Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which he completed in prison camp. The very short book was published when he was 22-years-old, and made him famous in the field of philosophy. Afterwards he left academia and worked as a school-teacher in a remote Austrian village, and as a gardener. He returned in 1929 to Cambridge to develop a different kind of philosophical approach, often called his “later philosophy.” This included his famous book Philosophical Investigations (published after his death in 1953), as well as the text below.

The following passages are adapted from class-notes of students in a course given by Wittgenstein at Cambridge University in 1938 (published in English as Lectures and Conversations – on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Beliefs).

For Wittgenstein, in order to understand the meaning of a word (such as “beautiful”), we need to examine how people use it in ordinary conversations. Every word is associated with typical gestures, facial expressions, behaviors, interactions, circumstances – or what Wittgenstein calls “a language-game.” Therefore, in order to understand what “beautiful” means, we need to understand the language-game around this word.

The word “beautiful” is an adjective, but when we examine the language-game of this word we realize that people don’t use it to refer to a specific quality, like “square” or “red” of “big.” Wittgenstein argues that the word functions as an interjection similar to “Wow!” or “Great!”

Wittgenstein also argues that the word “beautiful” is not very important in the language-game of aesthetic appreciation. When we evaluate a painting, or analyze a poem, or admire a dress – we don’t focus on “beauty” but rather on what is aesthetically correct or accurate.

1. The subject of Aesthetics is very big and entirely misunderstood, as far as I can see. The use of words such as “beautiful” is more likely to be misunderstood than the use of most other words, if you look at the linguistic form of the sentences in which they occur. “Beautiful” is an adjective, so you are inclined to say: “This thing has a certain quality, the quality of being beautiful.”

4. I have often compared language to a tool-box, containing a hammer, a chisel, matches, nails, screws, glue. It is not by chance that all these things have been put together – but there are important differences between the different tools – they are used in a family of ways – although nothing could be more different than glue and a chisel. There is a constant surprise at the new tricks which language plays on us when we get into a new field.

5. […] If you ask yourself how a child learns the words “beautiful,” “fine,” etc., you will find that he learns them roughly as interjections. (“Beautiful” is an odd word to talk about because it is hardly ever used.) […]

What makes the word an interjection of approval? The game in which it appears, not the grammatical form of words. Language is part of a large group of activities – talking, writing, traveling on a bus, meeting a person, etc. We should concentrate not on the words “good” or “beautiful” themselves – they are not special at all, generally just subject and predicate (“This is beautiful”), but on the occasions on which they are said; on the enormously complicated situations in which the aesthetic expression has a place. And the expression itself has almost a negligible place.

7. A characteristic thing about our language is that a large number of words which are used in aesthetic contexts are adjectives – “fine,” “lovely,” etc. But you see that this is by no means necessary. You saw that they were first used as interjections. Would it matter if instead of saying “This is lovely!” I just said “Ah!” and smiled, or just rubbed my stomach?

8. It is remarkable that in real life, when typical judgements are made, aesthetic adjectives such as “beautiful” or “fine” play almost no role at all. Are aesthetic adjectives used in a musical criticism? You say: “Look at this transition,” or: “The passage here is incoherent.” Or you say in poetical criticism: “His use of images is precise.” The words you use are more similar to “right” and “correct” than to “beautiful” and “lovely.”

13. What does a person say when trying on a suit at a tailor’s shop? “That’s the right length,” “That’s too sort,” “That’s too narrow.” Words of approval play no role, although he will look satisfied when the coat suits him. Instead of “That’s too short” I might say, “Look!” Or, instead of “Right” I might say “Leave it as it is.” A good tailor may not use any words at all, but he may make a chalk mark and later change it. How do I show my approval of a suit? Mainly by wearing it often, liking it when I see it, etc.

35. In order to get clear about aesthetic words, you have to describe ways of living. We think that we have to talk about aesthetic judgement like “This is beautiful,” but in aesthetic judgment we don’t find these words at all. These words are used like a gesture, accompanying a complicated activity.

|

|

April Week 4 quotation

FRIEDRICH SCHILLER

|

|

Beauty elevates us towards harmony

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a German writer in the areas of philosophy, history, poetry, and theatrical plays. At an early age he started writing plays, and eventually became one of the most important playwrights in German history. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history in nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis. Schiller’s philosophical work is mainly about ethics, aesthetics, and human freedom. In his philosophy he often develops, in his own way, ideas that originate from Immanuel Kant. Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a German writer in the areas of philosophy, history, poetry, and theatrical plays. At an early age he started writing plays, and eventually became one of the most important playwrights in German history. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history in nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis. Schiller’s philosophical work is mainly about ethics, aesthetics, and human freedom. In his philosophy he often develops, in his own way, ideas that originate from Immanuel Kant.

The following passages are adapted from Schiller’s main philosophy book On the Aesthetic Education of Man (1794). This thin book is composed of 27 philosophical “letters” that are addressed to a fictional, anonymous reader. The central idea is that beauty can touch us and elevate us towards harmony.

The sense of Beauty, according to Schiller, is based on two impulses (instincts, drives) which move us: the “sensuous” impulse that relates us to physical reality and physical pleasure, and the “formal” impulse that relates us to the intellectual, rational, spiritual, abstract. Beauty creates an equilibrium between the two impulses. It thus creates harmony within us, and this gives us a sense of play, or playfulness, which means freedom, enthusiasm, and happiness. Furthermore, unlike personal tastes which differ from one person to another, ideal beauty is one, and it therefore unifies society and makes it harmonious.

From LETTER 12

Two opposite forces drive us, and since they drive us towards their object, they are appropriately called “impulses.” The first impulse, which I will call the sensuous, comes from the person’s physical existence, or from his sensuous nature. It tends to enclose him within the domain of time, and to make him a material being. […]

The second impulse, which we may call the formal impulse, comes from the person’s absolute existence, or from his rational nature. It tends to liberate his nature, to bring harmony into its many manifestations, and to maintain a stable identity throughout changes.

From LETTER 15

The object of the sensual impulse may be called “life” in the widest sense of the word. This concept refers to all material beings and everything that is immediately present to the senses. The object of the formal impulse may be called “form,” both in the figurative and the literal sense. This concept includes all the formal qualities of things, and all their relations to the intellectual faculties.

The object of the play impulse (which unifies the impulse of sensual matter and the impulse of form), can therefore be called living shape. This concept denotes all the aesthetic qualities of phenomena, which is what we call Beauty in the broadest sense of the term.

from LETTER 16

The interaction of the two opposing impulses, the association of the two opposing principles, is the origin of the beautiful, whose highest ideal is, therefore, the most perfect possible union and equilibrium between material reality and form. But this equilibrium always remains a mere idea which can never be completely achieved in actuality. In actuality, one element will always be dominant over the other, and the most that we can experience will be oscillation between the two principles, so that at one moment material reality is dominant, and at another moment form. The idea of beauty is something indivisible and unique, since only one single equilibrium can exist. But beauty in actual experience is always divided to two, since through oscillation the balance may be destroyed toward one side or the other.

from LETTER 18

Through beauty, the sensuous person is led to form and to thought. Through beauty, the spiritual person is brought back to matter, and he is restored to the world of the senses.

from LETTER 27

Although need may drive a person into society, and reason may give him social principles, only beauty can give him a social character. Only beauty brings harmony into society, because it establishes harmony in the individual. All other forms of perception divide a person, because they are exclusively based either on the sensuous, or on the intellectual part of his being. Only the perception of beauty makes him something whole, because it demands the cooperation of his two natures. All other forms of communication divide society, because they relate exclusively either to the individual’s private taste or private skills, and therefore to what distinguishes one person from another. Only the communication of the beautiful unites society, because it relates to what is common to all its members (which is the ideal unification of sensual matter and form). We enjoy the pleasures of the senses as individuals, but the nature of the human race that lives within us takes no part in these pleasures. Therefore, we cannot extend our sensuous pleasures into being universal, because we cannot make our own individuality universal. […] It is only beauty that we enjoy both as individuals and as representatives of the human race. […] Only beauty makes the whole world happy, and everyone forgets his limitations as long as he experiences beauty’s enchantment.

|

|

|

April Week 5 quotation

MARSILIO FICINO

|

|

Beauty is the harmony which love desires

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) was a major Italian Neo-Platonist philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born near Florence, spent most of his career under the patronage of the Medici family, and was also the tutor of Lorenzo the Magnificent. For Ficino, the task of the philosopher is to interpret and develop historical treasures of wisdom, since wisdom gradually manifests itself through history. He saw himself as a Platonist, although he went far beyond Plato’s doctrines. When Ficino was about 40-years-old, Cosimo de’ Medici made him the head of a new Platonic academy, which served to educate the youth and as a meeting point of intellectuals. Ficino wrote several influential philosophical works, among them translations into Latin of Plato and of Plotinus, which became standard translations in Europe for three centuries. Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) was a major Italian Neo-Platonist philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born near Florence, spent most of his career under the patronage of the Medici family, and was also the tutor of Lorenzo the Magnificent. For Ficino, the task of the philosopher is to interpret and develop historical treasures of wisdom, since wisdom gradually manifests itself through history. He saw himself as a Platonist, although he went far beyond Plato’s doctrines. When Ficino was about 40-years-old, Cosimo de’ Medici made him the head of a new Platonic academy, which served to educate the youth and as a meeting point of intellectuals. Ficino wrote several influential philosophical works, among them translations into Latin of Plato and of Plotinus, which became standard translations in Europe for three centuries.

The following passages are adapted from Ficino’s book A Commentary on Plato, in which he develops a philosophy of beauty and of love that is rooted in certain Platonic ideas. Love, Ficino explains, is the desire for beauty, and beauty is a harmony that produces an image of inner goodness. Since it is based on an image, beauty is not always accurate, so that there is true love and false love. If we find ourselves attracted to somebody who is not good, then this is not true love of beauty, but something else. True beauty makes us want to be beautiful and good.

from First Speech, Chapter 4

When we say “love” we mean the desire for beauty, because this is the definition of love among all philosophers. Beauty is a certain charm which is found primarily in the harmony among several elements. This charm is threefold: there is a certain charm in the soul – in the harmony of several virtues; charm is also found in material objects – in the harmony of several colors and lines; and similarly, charm in sound is the best harmony of several tones. There is, therefore, triple beauty: of the soul, of the body, and of sound. […] Love seeks the enjoyment of beauty, and beauty is related only to the mind, sight, and hearing. Love, therefore, is limited to these three, and a desire which rises from the other senses is not love but lust or madness.

Further, when love desires human beauty, then since the beauty of the human body consists in a certain harmony, and since harmony is a kind of temperance, it follows that love seeks only what is temperate, moderate, and well-behaved. Pleasures and sensations that are impulsive and irrational unbalance the person’s mind, and are not what love wants, but rather what it hates and avoids, because they are the opposites of beauty. Lust drags a person down to greed and disharmony, and therefore attracts him to ugliness, whereas love attracts beauty.

from Fifth Speech, Chapter 1

There is both an interior and an exterior perfection: the interior we call goodness, and the exterior we call beauty. […] We notice this distinction in everything. For example, in precious stones, as the natural philosophers claim, a well-balanced combination of the four elements in the interior produces a brilliance of the exterior. […] Likewise, virtue of the soul is expressed most clearly through beauty in words, in actions, and in deeds. The heavens, too, are bathed in brilliant light through their own sublime essence.

In all these cases, an internal perfection produces the external perfection. The former we call “goodness,” the latter “beauty.” This is why we say that beauty is the blossom of goodness. This blossom attracts like a bait, so that the hidden interior goodness attracts those who see it. But since the understanding of our minds originates from the senses, we would never know and never desire the goodness that is hidden in the inner nature of things, unless we were led to it by its exterior appearance. This is the wonderful usefulness of beauty, and of the love that is associated with it.

These examples, I think, show that there is much difference between real goodness and its mere appearance, like between a seed and its flower. Just as the blossoms of trees grow from the seeds and also produce seeds, the same is with beauty which is the blossom of goodness: Since it grows out of goodness, it leads those who love it to the good.

Chapter 5

The appearance and the shape of a well-proportioned person agrees with the idea of humankind which our soul receives from the author of everything. Therefore, if an image of a person, received through the senses and going into the soul, disagrees with the idea of person which the soul possesses, he immediately displeases us, and we dislike him as being ugly. Therefore, it happens that some people, when they meet us, immediately please or displease us, and we do not know why. And naturally so, since the soul, preoccupied with the body, does not reflect on the Ideas which are innate in us.

|

|

|

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a German writer in the areas of philosophy, history, poetry, and theatrical plays. At an early age he started writing plays, and eventually became one of the most important playwrights in German history. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history in nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis. Schiller’s philosophical work is mainly about ethics, aesthetics, and human freedom. In his philosophy he often develops, in his own way, ideas that originate from Immanuel Kant.

Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) was a German writer in the areas of philosophy, history, poetry, and theatrical plays. At an early age he started writing plays, and eventually became one of the most important playwrights in German history. As a young man he studied medicine and became a military doctor in Stuttgart, but did not like this position and escaped to Weimar. He became a professor of philosophy and history in nearby Jena. Together with Goethe, he founded the influential Weimer Theater. He died at the age of 45 from tuberculosis. Schiller’s philosophical work is mainly about ethics, aesthetics, and human freedom. In his philosophy he often develops, in his own way, ideas that originate from Immanuel Kant.

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) was a major Italian Neo-Platonist philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born near Florence, spent most of his career under the patronage of the Medici family, and was also the tutor of Lorenzo the Magnificent. For Ficino, the task of the philosopher is to interpret and develop historical treasures of wisdom, since wisdom gradually manifests itself through history. He saw himself as a Platonist, although he went far beyond Plato’s doctrines. When Ficino was about 40-years-old, Cosimo de’ Medici made him the head of a new Platonic academy, which served to educate the youth and as a meeting point of intellectuals. Ficino wrote several influential philosophical works, among them translations into Latin of Plato and of Plotinus, which became standard translations in Europe for three centuries.

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) was a major Italian Neo-Platonist philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born near Florence, spent most of his career under the patronage of the Medici family, and was also the tutor of Lorenzo the Magnificent. For Ficino, the task of the philosopher is to interpret and develop historical treasures of wisdom, since wisdom gradually manifests itself through history. He saw himself as a Platonist, although he went far beyond Plato’s doctrines. When Ficino was about 40-years-old, Cosimo de’ Medici made him the head of a new Platonic academy, which served to educate the youth and as a meeting point of intellectuals. Ficino wrote several influential philosophical works, among them translations into Latin of Plato and of Plotinus, which became standard translations in Europe for three centuries.

READER`S LETTER

READER`S LETTER