|

SØREN KIERKEGAARD |

|||||

|

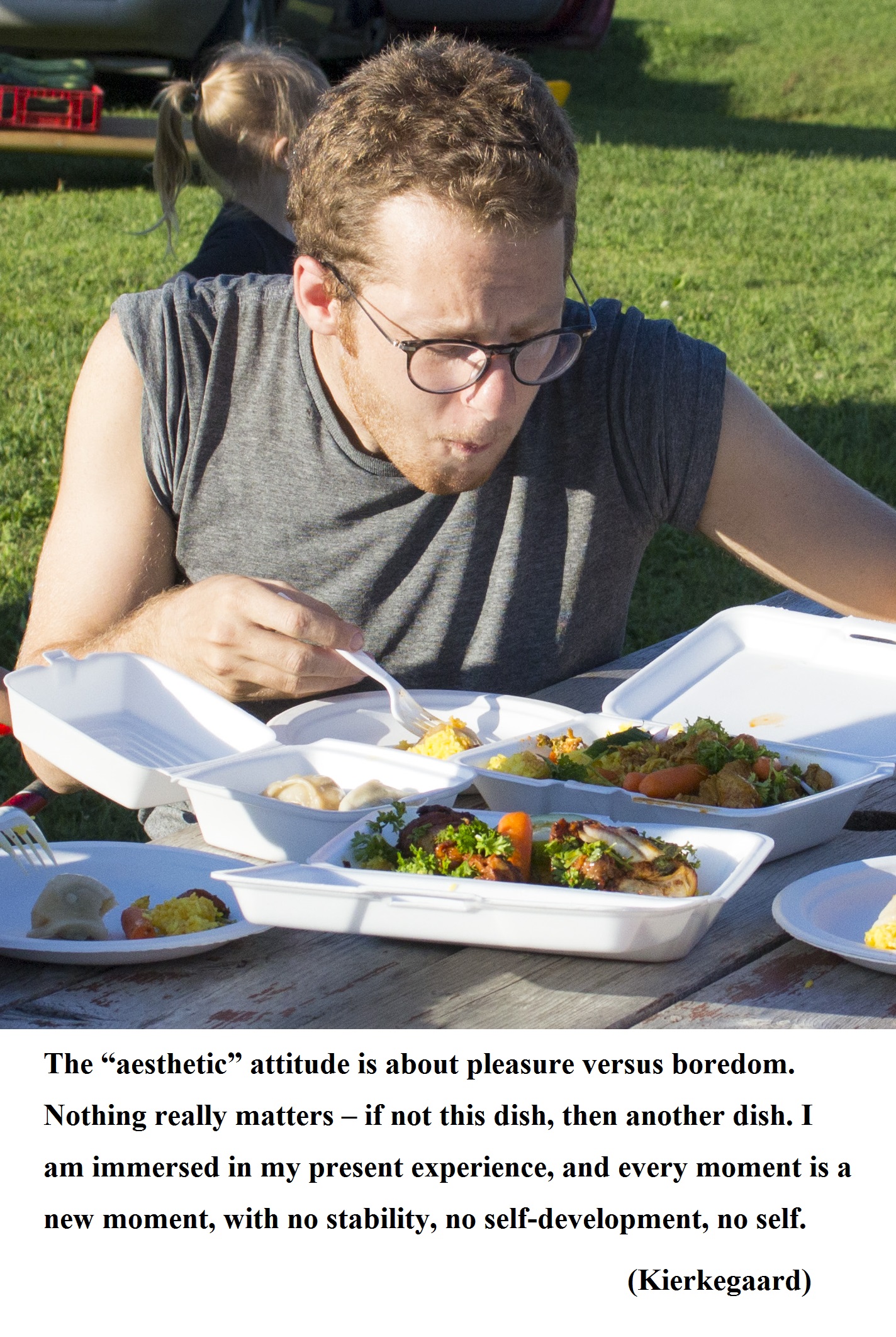

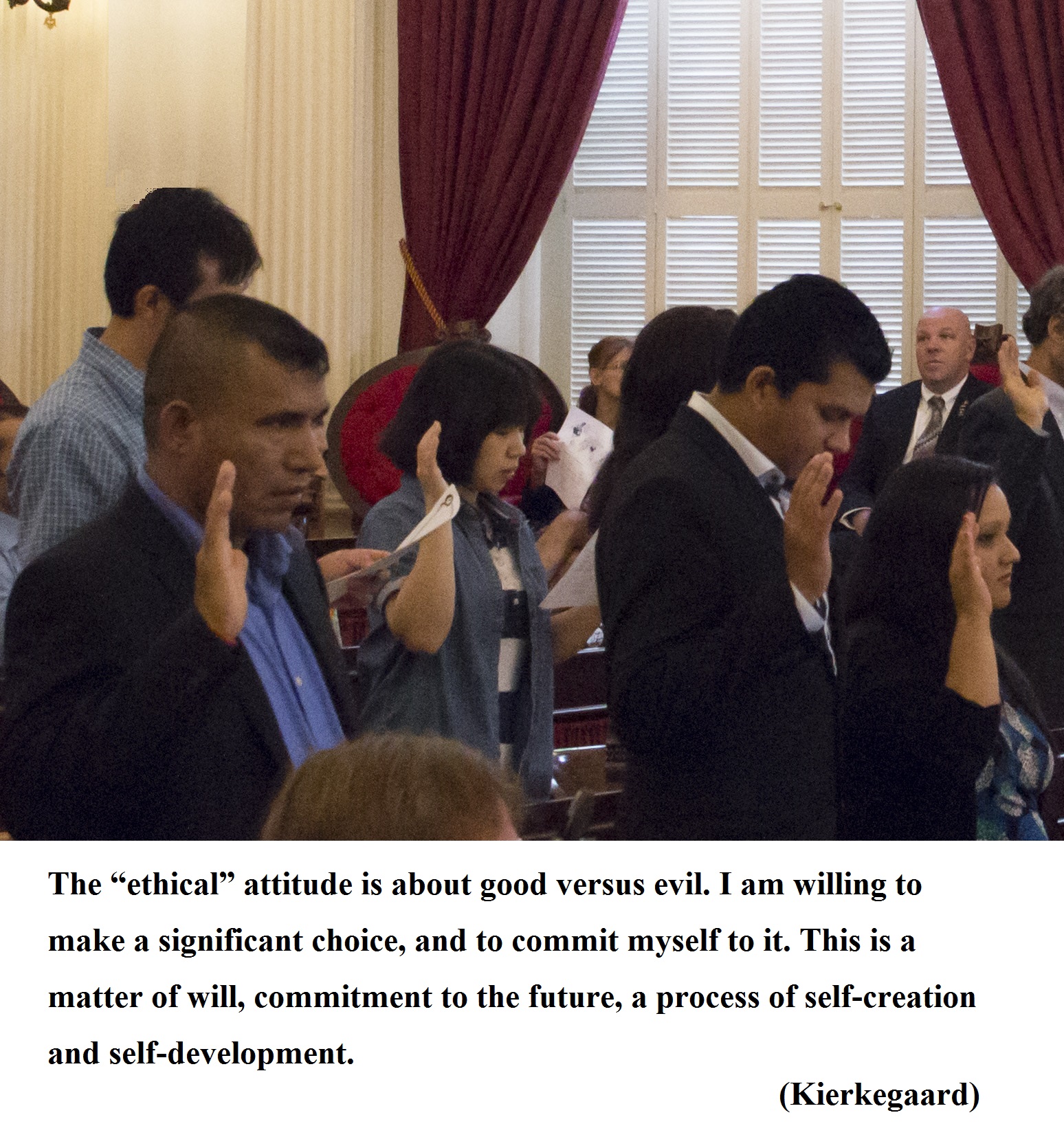

The aesthetic versus the ethical The following text is adapted from Part 1 of Kierkegaard’s famous book Either/Or (1843). As in many of his books, Kierkegaard does not present one unitary theory. Rather, the book expresses several different voices, each one written by a different imaginary writer, sometimes in the form of letters, sometimes in the form of a personal diary, a poem, etc. In this way Kierkegaard presents to the readers several different perspectives on life, and he encourages them to find themselves in them.

My either/or is not primarily about the choice between good and evil. It is about the choice between good-and-evi

l and excluding them. It is the question about the coordinates through which you would live and relate to existence. It is true that the person who has chosen good-and-evil chooses good, but this becomes evident afterwards. Because the aesthetic is not the evil but neutrality, and this is why the ethical constitutes the choice. The question is not, therefore, choosing between willing the good OR willing the evil, but rather choosing to WILL. And this choice posits the good and the evil.

SOLITUDE AS AN ESCAPE FROM ONESELF Kierkegaard’s extensive writings revolve primarily around the issue of how to live truly or authentically (or how to be a Christian, as he sometimes phrases it). For him, living truly means living with one’s entire being, with passion and commitment and faith. Most people, however, live a dull life of self-deception, so they do not really live. The following text is adapted from Kierkegaard’s book SICKNESS UNTO DEATH, published in 1849. Here Kierkegaard discusses what he calls “despair,” which is a state in which one is disconnected from the eternal, or God, and thus loses one’s own self. Often the individual is not aware of his situation, which means that he is not aware of his own despair. Despair is therefore like a sickness which the sick person may or may not be aware of. Kierkegaard distinguishes between three kinds of despair: Despair that comes from ignorance of one’s self, despair that comes from weakness and inability to accept one’s self, and despair that comes out of defiance. The following text is adapted from Kierkegaard’s description of the second kind of despair. In his usual ironic style, he tells us that the despairer often feels a need for solitude as an escape from his own weakness. Thus, a person’s need for solitude shows that he has enough spirit to feel the need for the eternal, but is too weak to act on this knowledge. […] The despairer understands that it is a weakness to take so seriously earthly matters, and that it is a weakness to despair. But then, instead of turning sharply away from despair to faith and humbling himself for his weakness, he becomes more deeply absorbed in despair and he despairs over his weakness. Now he becomes more conscious of his despair. Recognizing that he is in despair about the eternal, he despairs over himself that he is weak enough to give such importance to earthly matters. This now becomes his despairing expression for the fact that he has lost the eternal and himself. […] This despair refers to the formula: In despair at not willing to be oneself. Just as a father disinherits a son, so the self is not willing to recognize itself after it has been so weak. In its despair, the self cannot forget this weakness, it hates itself, it will not humble itself in faith under its weakness in order to gain itself again. […] And our despairer is introverted enough to keep every intruder (that is, every person) at a distance from the topic of the self, while outwardly he is completely "a real man." He is a university man, husband and father, an unusually competent civil official even, a respectable father, very gentle to his wife, and he is carefulness itself with respect to his children. And a Christian? Well, yes, sort of. However, he prefers to avoid talking about the subject, although he willingly observes, with a melancholic joy, that his wife engages in devotions. […] On the other hand, he often feels a need of solitude, which for him is a vital necessity – sometimes like breathing, at other times like sleeping. The fact that he feels this vital necessity more than other people is also a sign that he has a deeper nature. Generally, the need of solitude is a sign that there is spirit in a person after all, and it indicates how much spirit there is. People who are purely trivially inhuman, and too human, feel so little need of solitude that like certain social birds (the so-called love birds) they immediately die if they have to be alone for an instant. Just as the little child must be put to sleep with a lullaby, so these people need to be tranquilized with the hum of society before they are able to eat, drink, sleep, pray, fall in love, etc. […] The introverted despairer thus lives through hours which, although they are not lived for eternity, have nevertheless something to do with the eternal, because they are about the relationship of one’s self to itself – but he really gets no further than this. So when his need for solitude is satisfied, he goes outside himself as it were – even when he goes inside to converse with wife and children. What makes him so gentle as a husband and so caring as a father is, apart from his good-nature and his sense of duty, that he admits his weakness to himself, in his most inward reserves. If it was possible for anyone to enter his introversion and say to him, “This is in fact pride, you are proud of yourself,” he would probably not admit it to another person. He might probably admit that there is something in it when he is alone with himself. But his emotions when he pictures his weakness would quickly make him believe again that it could not possibly be pride. The fact is that he is in despair precisely over his weakness – as if it is not pride to give so much importance to your weakness, as if the reason he could not endure his weakness was not his desire to be proud of himself. If one said to him, “This is a strange complication, a strange sort of knot, because your whole misfortune is that your thinking is twisted. Without it, your path could be quite normal: You must travel through the self’s despair to faith. You are right about your weakness, but it is not over this you must despair. The self must be broken in order to become a self, so stop despairing over it.” If one talked to him like this, he would perhaps understand it in a clear unemotional moment, but soon emotion would return to see falsely, and so again he would take the wrong turn into despair. |

|||||

. ......

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.