Edmund Burke (1729–1797)

The Terror of the Sublime

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) was a British philosopher and politician. He grew up in Dublin, Ireland, which was then part of Britain, and after college education moved to London. He worked in several positions while writing and publishing several philosophy books. In his mid-thirties he entered a political career, was elected to the British House of Commons, and remained there for almost 30 years. As a good speaker he gave many speeches, many of which he later published. He died at the age of 68 after severe stomach problems.

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) was a British philosopher and politician. He grew up in Dublin, Ireland, which was then part of Britain, and after college education moved to London. He worked in several positions while writing and publishing several philosophy books. In his mid-thirties he entered a political career, was elected to the British House of Commons, and remained there for almost 30 years. As a good speaker he gave many speeches, many of which he later published. He died at the age of 68 after severe stomach problems.

The following passages are adopted (some linguistic simplification) from one of Burke’s earliest books, Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and BeautifuL (1756). The book is known for being the first to argue that beauty and sublimity exclude each other. While the experience of beauty is pleasant, the experience of the sublime is based on the feeling of terror.

Part 1, Section 7: Of the sublime

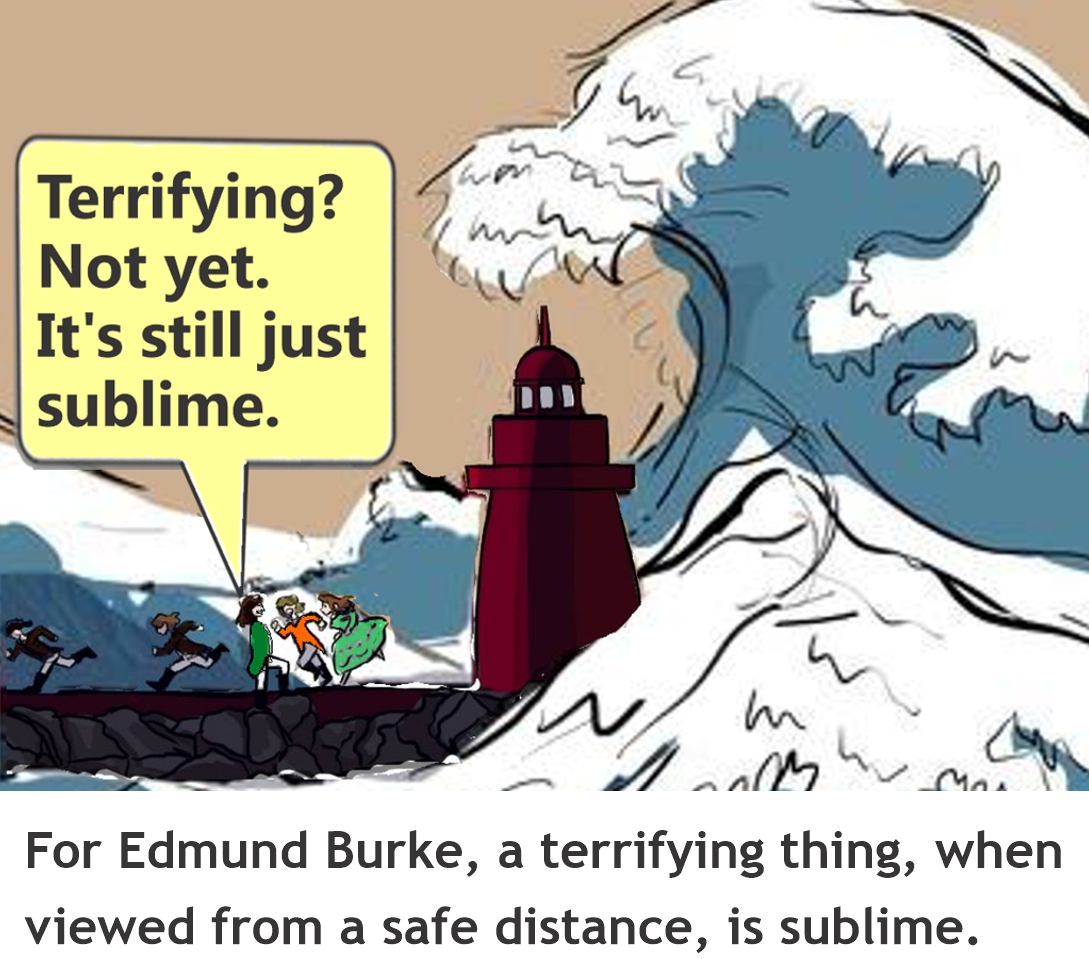

Whatever tends in any way to excite the ideas of pain and danger – that is to say, whatever is in any way terrible, or refers to terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror – is a source of the sublime. In other words, it produces the strongest emotion which the mind can feel. I say the “strongest emotion” because I am convinced that the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those of pleasure. […] When danger or pain approach us too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible. But at certain distances, and with certain variations, they may be – and they are – delightful, as we experience every day.

Part 2, Section 1: The emotions caused by the sublime

The emotion caused by what is great and sublime is astonishment. And astonishment is the state of the soul in which all the motions of the soul are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case, the mind is filled so completely with its object that it cannot entertain any other matter, and thus it cannot reason about that object. Hence, the great power of the sublime arises, and this power, far from being produced by reasoning, comes before reasoning, and it moves us with an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I said, is the effect of what is sublime in its highest degree. The weaker effects of the sublime are admiration, reverence, and respect.

Section 2: Terror

No passion robs the mind of all its powers to act and to reason as effectively as fear. Since fear is an apprehension of pain or death, it operates in a way that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible to our sight is sublime too, whether because of its great size or some other reason. Because it is impossible to look at anything as insignificant, or contemptible, but also dangerous. There are many animals which, though far from being large, yet are capable of raising ideas of the sublime, because they are viewed as objects of terror, such as snakes and poisonous animals of almost all kinds. And things of great size, if we add to them the idea of terror, become without comparison greater. A vast plain of land is certainly no small idea, and the measure of such a land may be as extensive as the measure of the ocean, but can it ever fill the mind with something so great as the ocean itself? This is because of several causes, but mainly because the ocean is an object of no small terror. Indeed, terror is in all cases, whether openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.

No passion robs the mind of all its powers to act and to reason as effectively as fear. Since fear is an apprehension of pain or death, it operates in a way that resembles actual pain. Whatever therefore is terrible to our sight is sublime too, whether because of its great size or some other reason. Because it is impossible to look at anything as insignificant, or contemptible, but also dangerous. There are many animals which, though far from being large, yet are capable of raising ideas of the sublime, because they are viewed as objects of terror, such as snakes and poisonous animals of almost all kinds. And things of great size, if we add to them the idea of terror, become without comparison greater. A vast plain of land is certainly no small idea, and the measure of such a land may be as extensive as the measure of the ocean, but can it ever fill the mind with something so great as the ocean itself? This is because of several causes, but mainly because the ocean is an object of no small terror. Indeed, terror is in all cases, whether openly or latently, the ruling principle of the sublime.

Section 3: Obscurity

To make anything very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary. When we know the full extent of any danger, when we can accustom our eyes to it, much of the fear disappear. Everyone will note this, if he considers how much night adds to our dread, in all cases of danger, and how much the notions of ghosts and goblins, of which nobody can form clear ideas, affect those minds which believe in the popular stories about such beings. Those tyrannical governments which are founded on people’s emotions, and principally on the emotion of fear, keep their leader away from the public eye as much as possible. This policy has been the same in many cases of religion. Almost all the pagan temples were dark. […] For this purpose, too, the Druids performed all their ceremonies in the middle of the darkest woods, and in the shadow of the oldest and most spreading oak-trees.

Section 5: Power

Besides those things which DIRECTLY suggest the idea of danger, and those which produce a similar effect from a mechanical cause, I know of nothing that is sublime which is not some form of power. And this branch of the sublime [=power] rises as naturally as the other two branches [largeness and obscurity] from terror – the common root of everything that is sublime. […] In short, wherever we find strength, and however we look upon power, we shall always observe the sublime as associated with terror, while contempt is associated with a strength that is submissive and harmless.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.