|

SOPHIE DE CONDORCET (1764-1822) |

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. CAUSES OF SYMPATHY | 2. FRIENDSHIP | 3. THE PLEASURES OF MORALITY |

Letters on Sympathy is a series of eight short philosophical essays which she wrote as letters to a person called “C” (perhaps her husband), and published in 1798. They were probably never intended to be real letters, and never sent to anybody. This short book discusses the nature of sympathy, and at several points reacts to the views of the Scottish thinker Adam Smith – an important economist and philosopher who attended her salon, and whose book she translated to French.

The book begins with the following paragraph:

It seems to me, my dear C***, that a human being has nothing more interesting to think about than the human being himself. Is there really any activity that is more satisfying and enjoyable than to direct the soul’s look to itself, to study how it works, to identify its movements, to use our mind to observe and speculate about one another, and to try to grasp the hidden and elusive laws that govern our thoughts and our feelings? Furthermore, to be often with oneself seems to me the most pleasant and wise way of life. It can combine the pleasures of wisdom and philosophy with the pleasures that come from strong deep feelings. It puts the soul in a state of well-being that is the main ingredient of happiness, and is the frame of mind most favorable to the virtues.

|

TOPIC 1. CAUSES OF SYMPATHY |

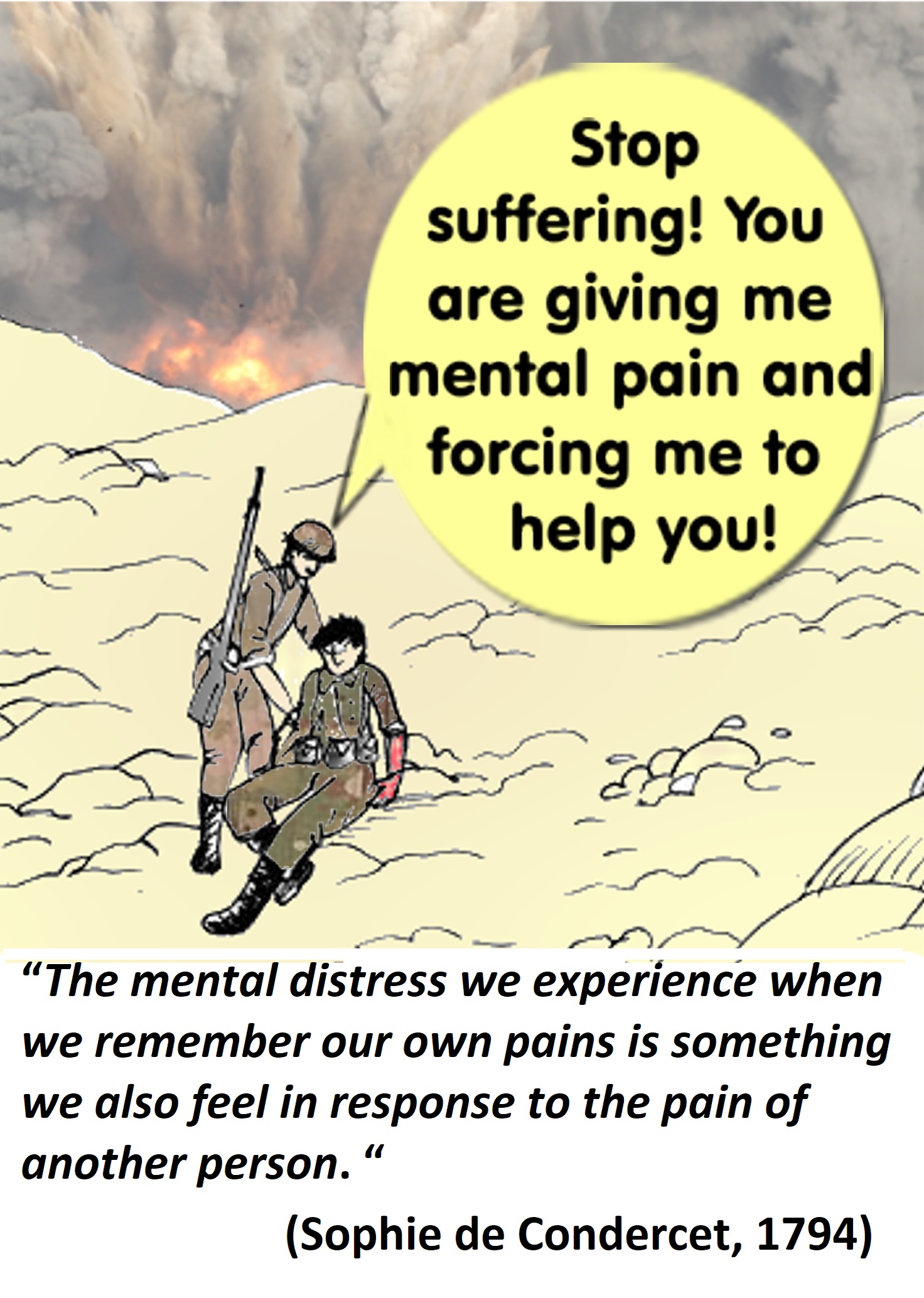

De Condorcet devotes the first chapter (or “letter”) of her book to issue: Why do we feel sympathy towards others? How can the pain of other people, which is not our pain, make us sympathize with them and feel bad for them? Her answer is based on an important distinction which she makes between two kinds of pain: the physical pain itself, and the mental distress which accompanies it. For example, when we are injured, we feel both a physical pain and a general sense of mental distress. Thus, when we see another person injured, we do not feel his physical pain of course, but we feel the same mental distress. Our sympathy for the suffering person is based on our own mental distress, which we remember from our own case.

De Condorcet devotes the first chapter (or “letter”) of her book to issue: Why do we feel sympathy towards others? How can the pain of other people, which is not our pain, make us sympathize with them and feel bad for them? Her answer is based on an important distinction which she makes between two kinds of pain: the physical pain itself, and the mental distress which accompanies it. For example, when we are injured, we feel both a physical pain and a general sense of mental distress. Thus, when we see another person injured, we do not feel his physical pain of course, but we feel the same mental distress. Our sympathy for the suffering person is based on our own mental distress, which we remember from our own case.

The following text is adapted from Letter 1 of de Condorcet's book Letters on Sympathy (1798).

Sympathy is the tendency which we have to feel as other people feel. […] Every physical pain produces a compound feeling in the person: First, it produces a localized pain in the body-part where the cause of pain acted. Second, it also produces a painful experience in all our organs, an experience that is quite different from the localized pain, and which always accompanies the localized pain, but can continue to exist without it.

To understand how different these two pains are, notice what you feel the moment the localized pain stops. Often, we experience both a pleasure that the pain stopped, and a general feeling of malaise. This feeling of malaise is sometimes very painful. If something prolongs it, it can even become more difficult to bear than local pains that are more intense but shorter. This is because the bodily organs in which the general malaise occurs are the most essential for our vital functions, and also for the faculties that enable us to sense and to think.

This general experience of malaise is renewed when we remember the physical hurts which we have suffered in the past. This makes the memory of these harms distressing, and some of this distress always accompanies this memory. Although this experience can certainly vary to some degree, it is nevertheless the same experience for many different local pains, at least when they are similar in intensity or in character. […]

The painful impression which we experience when we remember our own localized pains from the past is something which we also feel in response to the pain of another creature, when we see signs that he is suffering, or when we know it in some other way. In fact, as soon as we have an abstract idea of pain (thanks to our developed mind and our repeated experience of pain) this abstract idea by itself renews in us the general impression of distress in all our organs, which is the result of physical pain.

Thus, pain has an effect that follows equally both from its physical presence and from its mental presence. By “its mental presence” I mean both the idea of pain that our memories give us, and the idea which we get from seeing or knowing about other people’s pain. So sympathy for physical pains comes from the fact that the sensation of physical pain produces in us a compound sensation, and part of it can be revived simply by the idea of pain. […]

The experiences of pleasure reach us through the same organs as the impressions of pain, and they follow the same laws. Like physical pain, all physical pleasure produces in us a particular sensation of pleasure in the organ that first receives it, and this localized pleasure is accompanied by a general sense of well-being. This general sensation can reappear at the sight of pleasure, just as the general impression of pain on our organs reappears at the sight of pain.

Therefore, we can have sympathy towards other people’s physical pleasures just as towards their physical pain. But this sympathy is harder to arouse, and consequently it is more rare, because pleasure is less intense than pain, so that this general impression of pleasure on our organs is less easily awakened. And also, because almost all physical pleasures have something that is self-contained – something that shuts out everything else – and this gives us the idea and the feeling of absence, which contradicts – and may even destroy the pleasant impression that the idea of the other person’s pleasure could arouse in us.

[…] What do we not owe to sympathy! Sympathy, from its first faint beginnings, is the root cause of the feeling of humaneness that has such precious effects. It acts against some of the evils that come from personal interests in large societies, and it fights against the force of oppression that we encounter everywhere we go, which can be destroyed only through centuries of enlightenment that attack the vices that produced it. In the face of so many passions that oppress the weak or push aside the unfortunate, humaneness begs – secretly but from the bottom of its heart – for the sake of humankind, and it avenges its injustice by awakening the sentiment of natural equality.

|

TOPIC 2. FRIENDSHIP |

As we have seen, in the first chapters of her book Letters on Sympathy, Sophie de Condorcet discusses what she calls “general sympathy” – in other words, sympathy for a human being as a human being. In the third “letter” (chapter) of the book she focuses on sympathy for a specific person who attracts our attention and our heart. This attraction, which she calls “individual sympathy” or “particular sympathy,” may later develop into the love for a friend.

As we have seen, in the first chapters of her book Letters on Sympathy, Sophie de Condorcet discusses what she calls “general sympathy” – in other words, sympathy for a human being as a human being. In the third “letter” (chapter) of the book she focuses on sympathy for a specific person who attracts our attention and our heart. This attraction, which she calls “individual sympathy” or “particular sympathy,” may later develop into the love for a friend.

LETTER 3: INDIVIDUAL SYMPATHY

Today, my dear C***, I want to speak to you about individual sympathy, the sympathy that creates between people the intimate bonds that are necessary for their perfection and happiness. It brings hearts together and connects them with the most tender affections.

[…]

When we see somebody for the first time, we look at his features, and we seek the person behind the face. If the face is graceful or beautiful even a little bit, or if it is unusual in some way, we inspect it carefully, and we try to grasp its feelings and to figure out which of them influence it most often. There isn’t anybody whose appearance does not immediately give us some idea of his character, or at least makes us think something about his mind, whether favorably or not.

Our first impressions which are based on facial features soon grow, or change, or stop, according to our impressions of the person’s movements, his mannerisms, his speech, and any contrast between what he says and does. Because through the gaze the person’s moral character appears, through his speech the movements of his soul are revealed, and through his gestures his habits are exposed. On the basis of all this, when we believe that we have found the qualities that especially interest us – sometimes because they are connected to our own qualities, or because we value them highly, or because they strike us as special – then a wave of good-will rises within us, and it is directed at the person who appears gifted with those qualities. We feel attracted to him. We enjoy looking at him.

[…] Our enthusiasm comes from the ability of our soul to represent to itself, all at once but quite vaguely, all the pleasures and all the pains that we might get from certain situations with this person, or from his existence and our relationship with him or her. This representation unites in a single moment what in real life would take months, years, sometimes even a lifetime to experience. Thus, enthusiasm sees the other person in an exaggerated way.

[…] It is necessary for us to have esteem for the person in order to acquire the trust and freedom which our soul can have in the first stages of sympathy. Only with esteem can we love with the full force of our sensibility. It is somehow the only medium where our affections develop, where the heart can let go, and consequently where it fully develops. In honest souls, esteem is always the silent companion of individual sympathies […].

A person who is worthy of esteem is happy to esteem others. His heart is easily moved by the mere thought of a good action, and it is tied and attached to anybody he thinks can perform such an action. He is happy to be with him, and their brotherhood of virtue creates between them freedom and equality, which they may experience tenderly like the tenderness between the closest blood and natural relatives.

If the first movements of sympathy are feelings for somebody we hardly know just because of his looks, and if his behavior and a few words are enough to make his presence a pleasure, and if mere esteem creates in us a feeling of good-will and freedom, then we can understand the power of deep sympathy, and what the attraction of friendship can be. We can say that the attraction of friendship begins before the friendship starts, as soon as we can imagine the friendship coming. In fact, as soon as we have the idea of someone who might befriend us and who has deep and delicate affections, we feel pleasure because we imagine in our soul all the tenderness that friendship can bring us. This feeling is already a joy.

[…]

It is so true that the pleasure we find in loving comes (at least in the case of friendship), to a large extent, from our pleasure of making people happy through our affections; so that only generous souls can love. Souls that lack magnanimity or nobility, or that have been corrupted by selfishness, might want to be loved and might seek love’s delight and fruits, but only generous hearts who can be touched by the happiness of others really know how to love.

|

TOPIC 3. THE PLEASURES OF MORALITY |

In the second half of her book on sympathy, in Letters 5-8, De Condorcet discusses the origin of morality. Her question is: What motivates people to act morally – to do good to others, to follow their moral obligations, to do what is right and just?

In the second half of her book on sympathy, in Letters 5-8, De Condorcet discusses the origin of morality. Her question is: What motivates people to act morally – to do good to others, to follow their moral obligations, to do what is right and just?

Her answer is: the pleasures of sympathy. The basis of morality is our natural tendency to feel sympathy towards others, especially (but not only) towards those who suffer. This sympathy makes it a pleasure for us to do good to others. In fact, it gives us several kinds of pleasure: First, the pleasure of relieving somebody’s suffering; second, the pleasure which we will have later when we remember that we have relieved the suffering.

But morality is not just feelings. It must be based on general principles of reason. Moral behavior must be guided by moral obligations, not just by what you feel at the moment.

Moral obligations, for de Condorcet, are an abstract generalization of the pleasures of sympathy. They are the product of reason, when it reflects on our natural tendency to enjoy doing good. As a result, a third kind of pleasure enters the picture here: When we follow our reason and our moral obligations, we enjoy exercising our will-power and sensing our self-control.

The following text is adapted from Letters 5 and 6.

From Letter 5

We naturally feel satisfaction when we see, or even have the idea, of another person’s pleasure or well-being, and so it follows necessarily that we feel a selfish pleasure when we do this to other people. […] Another reason that increases the pleasure of doing good is the thought that we owe this pleasure to ourselves, and that consequently we hold in our hands the power to acquire it for ourselves, to reproduce it when we want. […]

We therefore feel a natural pleasure in doing good. But another feeling also arises from this pleasure: the satisfaction that we have done good. Just like in the case of physical pain, a suffering gives us, beyond the immediate local experience, a general unpleasant feeling throughout our body. We therefore experience personal pleasure when we remember someone else’s happiness. But for this to happen in our memory often, it must be linked to our own situation and to our own trains of thought, and this is what happens when we are the cause of it. Then this memory integrates itself into our intimate self-awareness, it becomes a part of us, it becomes habitual to us, and it produces in us a pleasant feeling that lasts much longer than the specific pleasure that originally produced it. So when we have done good to another person, the pleasure we get from our action is not dependent on the pleasure which this other person got from it. […]

Thus, the pleasure of doing good forms a long-term connection with the pleasure of having done good. This combined feeling becomes general and abstract, since we feel it again just by remembering good actions, even without remembering their particular circumstances. […] Happy is the person, my dear C***, who carries this feeling firmly in the depths of his heart and who dies feeling it! He alone has lived!

Similarly, the sight or idea of another person’s misfortune makes us experience a painful reaction, and the feeling is more intense when we are the voluntary or even involuntary cause of this misfortune. […] Just as the satisfaction of having done something good is integrated into our existence and makes us feel good, similarly the awareness of having done something wrong attaches itself to us and upsets our existence. It produces feelings of regret and remorse that bother us, afflict us, disturb us, and make us suffer, even when we no longer remember specifically the initial feeling of pain which our behavior had caused.

From Letter 6

So you see, my dear C***, that our actions follow two rules: REASON and JUSTICE. The second rule is simply reason reduced to a definite rule. We have already found very powerful inner motivations for obeying these two rules: the internal satisfaction of doing good to others, and remorse for having done something wrong to them. But there is also a third motivation: the immediate pleasure which we experience when we follow reason and perform an obligation. I am sure that the existence of these feelings is independent of other people’s opinions.

The pleasure we get from following reason seems to have the same source as the pleasure we get from feeling our own strength. We experience a pleasant feeling when we follow our reason because we tell ourselves that if we have an unreasonable impulse to do something cruel, then reason would give us a resource to resist the impulse and avoid the act. […] What more comforting and gentle feeling is there than recognizing through direct experience that we possess such a guide, such a protector of our happiness, such a supporter of our inner peace!

The pleasure we feel when we follow our reason is also combined with a sense of freedom, and of a sort of independence and control over any immediate cause that might be harmful to us. This pleasure thus reassures us, elevates us in our own eyes, and satisfies the natural inclination we all have to depend only on ourselves. This is because we have more confidence in our well-being when it is in our own hands.

The pleasure we experience when we follow our moral obligation is connected more directly to our sense of security, and to the comfort we feel that we are safe from feeling resentment, vengeance, and hatred. Our satisfaction that we avoided feeling regret is strengthened by the hope that we will never have to experience remorse. This is a superb hope because it banishes the idea of every inner obstacle to our happiness.

Philosophers

-

- Philosopher

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.