DEMOCRITUS |

PLEASURE, HAPPINESS AND CHEERFULNESS

Democritus of Abdera (second half of the 4th century BC) is known today primarily for his theory of atoms, which resembles to some extent modern scientific theories. In fact, he wrote many books about a variety of topics, including ethics, natural science, mathematics, music, and technical works. Only fragments of these works have survived, many of them quotations by Aristotle (who lived about two generations later).

The following are Democritus’s main fragments on the topic of happiness. Since many of them are very short, it is difficult to understand the context from which they were taken. It seems, however, that he valued happiness that is balanced, moderate, and free of excessive emotions and passions. This kind of happiness does not come naturally, but requires education and cultivation, a sense of cheerfulness, friends, and being satisfied with what one has.

31. Medicine heals the diseases of the body, wisdom frees the soul from passion.

61. Those whose character is well-ordered also have a well-ordered life.

71. Eventually, pleasures produce unpleasantness.

74. Accept no pleasure unless it is beneficial.

88. The envious person torments himself like an enemy.

99. Life is not worth living for the person who does not have even one good friend.

103. A person who loves nobody is, I think, loved by no one.

160. To live badly is not just to live badly, but to spend a long time dying.

170. Happiness, like unhappiness, is the property of the soul.

172. The same things from which we get good can also be for us a source of hurt, but we can avoid the hurt. For instance, deep water is useful for many purposes, and yet can be harmful, because there is danger of drowning. A technique has therefore been invented: instruction in swimming.

174. The cheerful person, who is driven towards words that are just and lawful, rejoices by day and by night, and is strong and free from care. But the person who neglects justice, and who does not do what he should, finds all such things unpleasant when he remembers any of them, and he worries and torments himself.

189. The best way for a person to lead his life is to be as cheerful as possible and to suffer as little as possible. This can happen if one does not seek pleasures in mortal things.

191. Cheerfulness is created for people through moderate enjoyment and harmonious life. Things that are too much or too little tend to change and cause great disturbance in the soul. Souls which are stimulated by great changes are neither stable nor cheerful. Therefore, one must keep one’s mind on what is attainable, be satisfied with what one has, pay little attention to things envied and admired, and not dwell on them in one’s mind. Rather, you should consider the lives of those who are in distress, and reflect on their intense suffering, so that your situation and possessions would seem to you great and enviable. And by stopping to desire more, you may stop suffering in your soul. Because a person who admires those who have possessions and who are called happy by others, and keeps thinking about them every hour, is constantly forced by his desire to do something new, and he risks doing something irreversible, and forbidden by law. Hence, one must not seek to get what others have, but must be content with what one has, and compare one’s own life with the life of those who are in a worse situation, and must consider himself better off than they. If you follow this way of thinking, you will live more peacefully, and you will expel those considerable curses in life: envy, jealousy, and spite.

194. The greatest pleasures come from the contemplation of noble works.

200. People who live without enjoying life are fools.

208. One should choose not every pleasure, but only pleasure concerned with the beautiful.

211. Moderation multiplies pleasures, and increases pleasure.

230. Life without celebration is a long road without an inn.

231. The right-minded man is somebody who is not grieved by what he doesn’t have, but enjoys what he has.

232. The pleasures that come most rarely give the greatest enjoyment.

233. If one steps beyond the appropriate amount, the most pleasurable things become most unpleasant.

235. All those who get their pleasures from the stomach, going beyond the appropriate amount of drinking or sexual pleasure, have pleasures that are only brief and short-lived – only during the moment of eating and drinking, but their pains are many. Because their desire for the same thing is always present, because when people get what they desire, the pleasures pass away quickly. And so, they have nothing good for themselves except for a brief enjoyment, after which their need for the same things returns again.

243. Many kinds of work are more pleasant than resting after you got what you were working for, or what you know you will get. But whenever there is failure to get it, then work is painful and hard.

286. Fortunate is the person who is happy with moderate means, and unfortunate is he who is unhappy with great possessions.

Philosophers

-

- Philosopher

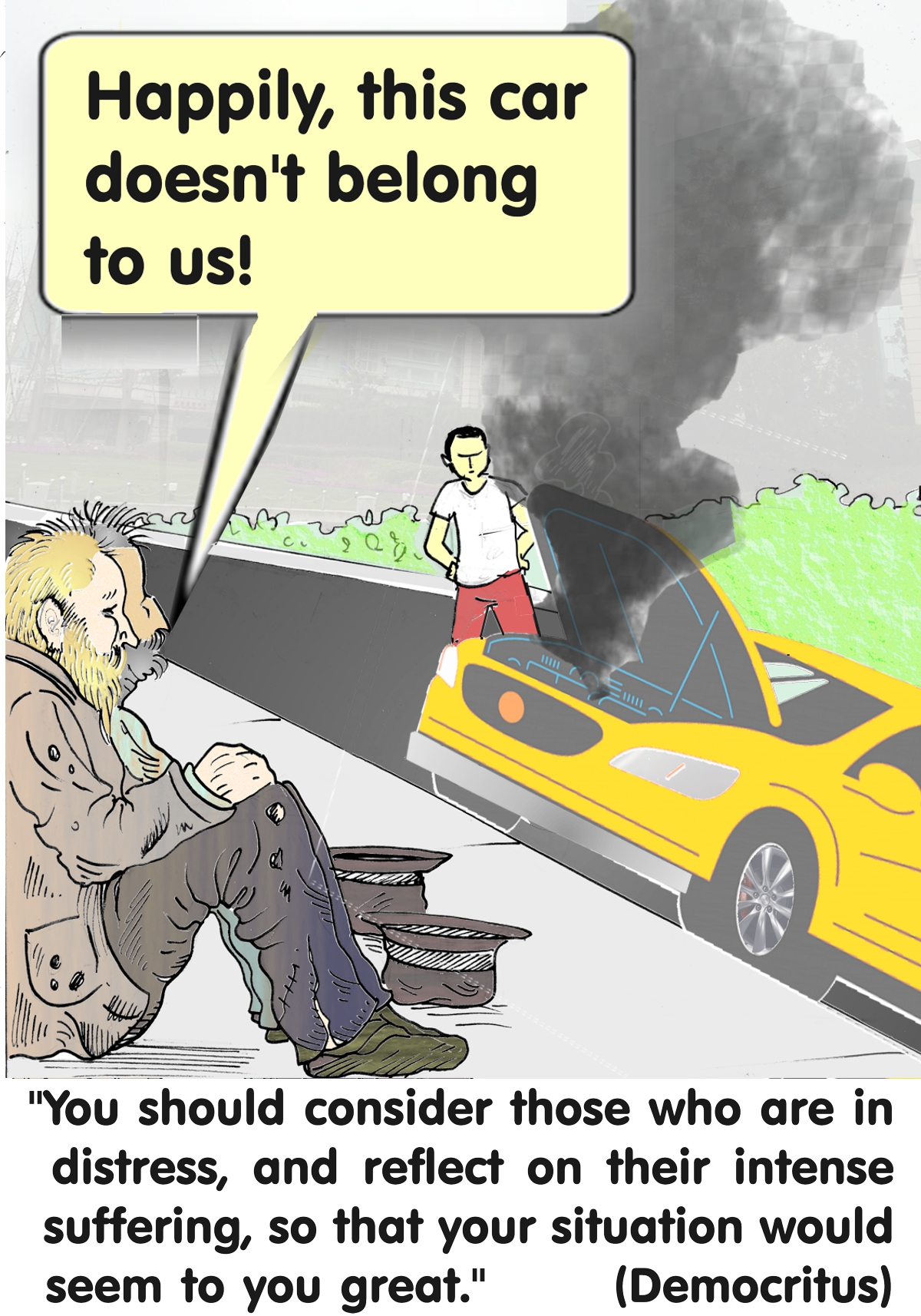

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.