DEATH

Happiness

VIRTUE

THE OTHER PERSON

Inner Freedom

MUSIC

ROMANTIC LOVE

SEX

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was born in Germany to a Jewish family and studied philosophy at several universities. She was a student of Heidegger at Marburg University and of Husserl at Freiburg University, and wrote her doctoral dissertation at Heidelberg University under the guidance of Jaspers. Since she was Jewish, she escaped Germany in 1933, and then escaped occupied France in 1940, and ended up in the USA, where she taught at several universities until her death. She wrote on a variety of topics and is regarded as one of the most important political philosophers of the 20th century. She is also known for her coverage and analysis of the trial of the Nazi war criminal Eichmann in Israel, in which she coined the expression “the banality of evil.” She died from heart attack at the age of 69.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was born in Germany to a Jewish family and studied philosophy at several universities. She was a student of Heidegger at Marburg University and of Husserl at Freiburg University, and wrote her doctoral dissertation at Heidelberg University under the guidance of Jaspers. Since she was Jewish, she escaped Germany in 1933, and then escaped occupied France in 1940, and ended up in the USA, where she taught at several universities until her death. She wrote on a variety of topics and is regarded as one of the most important political philosophers of the 20th century. She is also known for her coverage and analysis of the trial of the Nazi war criminal Eichmann in Israel, in which she coined the expression “the banality of evil.” She died from heart attack at the age of 69.

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. LABOR, WORK, ACTION | 2. THE MENTALITY OF UTILITY | ||||

| 3. THINKING AS DISAPPEARING | 4. THE MEANING OF FREEDOM | ||||

| 1. LABOR, WORK, ACTION |

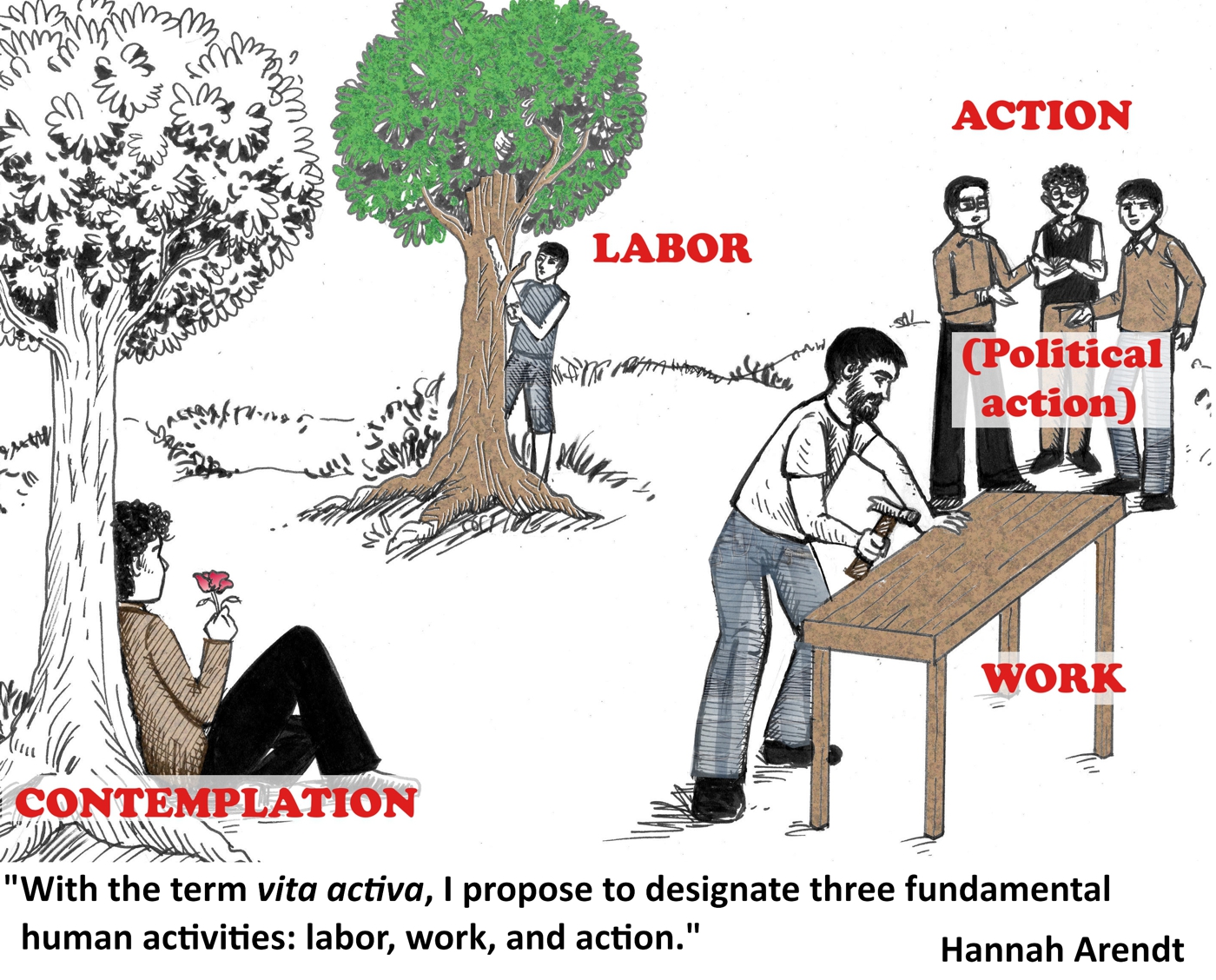

In her major book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt analyzes forms of Vita Activa – active way of life. She argues that ancient and pre-modern philosophy focused on Vita Contemplativa, which it regarded as the highest way of life, and as a result ignored and misunderstood the complexity and value of Vita Activa. Arendt’s attempts in this book is to develop a better understanding of Vita Activa, and to show how it can lead to political life, and thus to freedom and individuality. A central distinction in this book is between three forms of Vita Activa: labor, work, and action. LABOR is working for survival according to biological needs and cycles of life (eating, sleeping, etc.). This is the life of, for example, the poor farmer or the slave, which is dictated by necessities. WORK consists of producing products for consumption and use, thus creating cultural worlds of utilitarian objects – houses, furniture, cars, etc. This is the life of, for example, the carpenter or the tailor. ACTION, the highest form of Vita Activa, consists of creative, individual activity which takes place in the public realm and makes freedom and individuality possible. Action appears in an advanced historical stage of society. Unfortunately, Western society is sliding back to the utilitarian consumerist way of life (work), and even to labor.

In her major book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt analyzes forms of Vita Activa – active way of life. She argues that ancient and pre-modern philosophy focused on Vita Contemplativa, which it regarded as the highest way of life, and as a result ignored and misunderstood the complexity and value of Vita Activa. Arendt’s attempts in this book is to develop a better understanding of Vita Activa, and to show how it can lead to political life, and thus to freedom and individuality. A central distinction in this book is between three forms of Vita Activa: labor, work, and action. LABOR is working for survival according to biological needs and cycles of life (eating, sleeping, etc.). This is the life of, for example, the poor farmer or the slave, which is dictated by necessities. WORK consists of producing products for consumption and use, thus creating cultural worlds of utilitarian objects – houses, furniture, cars, etc. This is the life of, for example, the carpenter or the tailor. ACTION, the highest form of Vita Activa, consists of creative, individual activity which takes place in the public realm and makes freedom and individuality possible. Action appears in an advanced historical stage of society. Unfortunately, Western society is sliding back to the utilitarian consumerist way of life (work), and even to labor.

The following two texts are lightly adapted from the first few sections of The Human Condition. They introduce Arendt’s three-fold distinction between the three forms of Vita Activa, which is the foundation of her book.

From Chapter 1: VITA ACTIVA AND THE HUMAN CONDITION

With the term vita activa, I propose to designate three fundamental human activities: labor, work, and action. They are fundamental because each corresponds to one of the basic conditions under which life on earth has been given to man.

LABOR is the activity which corresponds to the biological process of the human body, whose spontaneous growth, metabolism, and eventual decay are tied to the vital necessities that are produced, and fed into, the life process by labor. The human condition of labor is life itself.

WORK is the activity which corresponds to the unnaturalness of human existence, which is not part of man’s repetitive life-cycles, and which is not necessary for survival. Work provides an “artificial” world of things, very different from all-natural surroundings. Within this world each individual life is housed, while this world itself is meant to last longer than any individual life and to transcend all individual lives. The human condition of work is worldliness.

ACTION, the only activity that happens between men directly, without the mediation of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men (not Man in general) live on the earth and inhabit the world. While all aspects of the human condition are somehow related to politics, this plurality is specifically the condition – not only the necessary condition, but the causal condition – of all political life. […] Action would be an unnecessary luxury, a capricious interference with general laws of behavior, if men were endless repetitions of the same model, with the same nature or essence, predictable like the nature or essence of any other thing. Plurality is the condition of human action because we are all the same – human, in such a way that nobody is ever the same as anyone else who ever lived, lives, or will live.

All three activities and their corresponding conditions are intimately connected to the most general condition of human existence: birth and death, natality, and mortality. Labor assures not only individual survival, but the life of the species. Work and its artifacts give some permanence and durability to the futility of mortal life and to the shortness of human life-time. Action, to the extent that it builds and preserves political bodies, creates the condition for remembrance, that is, for history. Labor and work, as well as action, are also rooted in natality, since they prepare and preserve the world for the constant flow of newcomers who are born into the world as strangers. However, of the three, action has the closest connection with the human condition of natality. The new beginning that is inherent in birth can be felt in the world only because the newcomer has the capacity to begin something anew, that is, to act. In this sense of initiative, an element of action, and therefore of natality, is inherent in all human activities. Moreover, since action is the political activity par excellence, natality, and not mortality, may be the central category of the political (as opposed to metaphysical) thought.

From Chapter 4: MAN: A SOCIAL OR A POLITICAL ANIMAL

The vita activa – human life which is actively engaged in doing something – is always rooted in a world of men and of man-made things which it never leaves or transcends completely. Things and men form the environment for any human activity, and it would be pointless without such location. Yet, this environment – the world into which we are born, would not exist without the human activity which produced it, as in the case of fabricated things: without the human activity which takes care of it, as in the case of cultivated land; or without the human activity which established it through organization, as in the case of the body politic. No human life is possible, not even the life of the hermit in nature’s wilderness, without a world which directly or indirectly testifies to the presence of other human beings.

All human activities are conditioned by the fact that men live together, but it is only action that cannot even be imagined outside the society of men. The activity of labor does not need the presence of others, although somebody who labors in complete solitude would not be human but an animal laborans [laboring animal] in the most literal meaning of the word. Man working and fabricating and building a world which is inhabited only by himself would still be a fabricator, although not homo faber, since he would lose his specifically human quality and instead be a god, a divine demiurge as Plato described him in one of his myths. […] Only action is the exclusive privilege of man. Neither a beast nor a god is capable of it, and only action is entirely dependent upon the constant presence of others.

| 2. THE MENTALITY OF UTILITY |

In part IV of her book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt discusses the meaning of WORK (which she distinguishes from LABOR, which is struggling for basic existence). Work, as she defines it, means producing artificial products and using them: knives and spoons, tables and chairs, houses, cars, machines. The world of work is therefore fundamentally different form the world of labor. The person of labor (Animal Laborans) who struggles to exist, follows the cycles of nature: tilling the land, growing animals, fishing, eating and sleeping, day and night, summer and winter. In contrast, the person of work (Homo Faber) – the person of production and products, creates an artificial world and lives in it. Work therefore frees us from labor and from the tyranny of nature. It also gives us the possibility of culture: public buildings and events, arts and crafts, furniture, kitchenware, houseware.

In part IV of her book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt discusses the meaning of WORK (which she distinguishes from LABOR, which is struggling for basic existence). Work, as she defines it, means producing artificial products and using them: knives and spoons, tables and chairs, houses, cars, machines. The world of work is therefore fundamentally different form the world of labor. The person of labor (Animal Laborans) who struggles to exist, follows the cycles of nature: tilling the land, growing animals, fishing, eating and sleeping, day and night, summer and winter. In contrast, the person of work (Homo Faber) – the person of production and products, creates an artificial world and lives in it. Work therefore frees us from labor and from the tyranny of nature. It also gives us the possibility of culture: public buildings and events, arts and crafts, furniture, kitchenware, houseware.

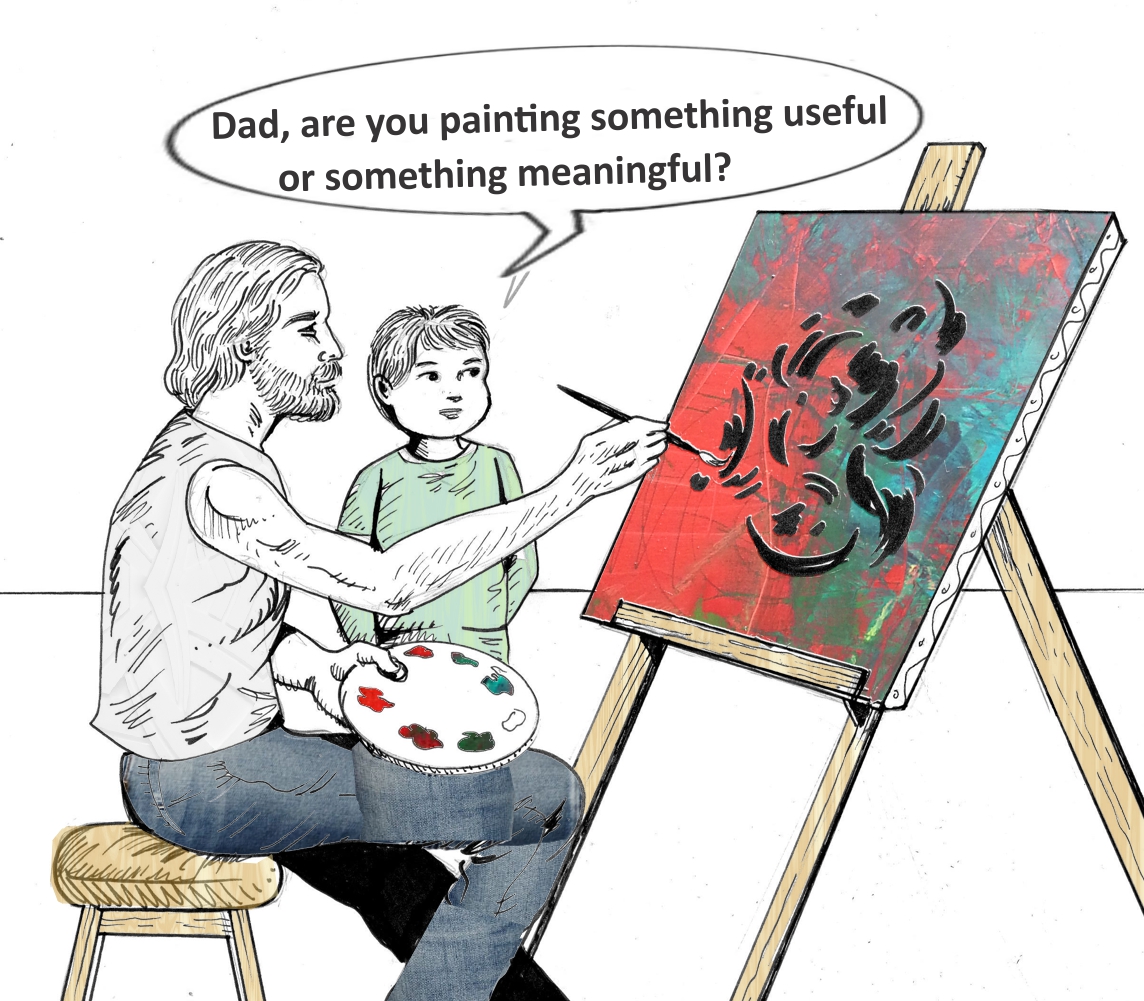

But work also has limitations and challenges, as Arendt explains in the following text (adapted for ease of reading). The world of work is governed by the values of instrumentality and utility. If you live in such a world, nothing is valuable to you unless you can use it for something. Nothing is meaningful in itself, because everything is just a tool for something else. Life is in danger of becoming meaningless. People start believing that the only meaningful thing is what serves me, in other words subjectivity – I myself.

As Arendt explains in later chapters of her book, only in the third stage of the Vita Activa – in ACTION (primarily political action), can humans find the possibility of meaning, as well as freedom and individuality.

From Chapter 21. INSTRUMENTALITY AND HOMO FABER

During the work process, everything is judged in terms of usefulness for the desired end [=goal], and for nothing else. […] The chair, which is the end of carpentering, can show its usefulness only by becoming a means [=an instrument for some purpose], either a means for comfortable living, or a means of exchange. The trouble with the utility standard, which is inherent in the activity of fabrication, is that the relationship between means and end [=instrument and goal] on which it relies is very much like a chain, whose end can serve again as a means in some other context. In other words, in a strictly utilitarian world, all ends must be transformed into means for some further ends.

This perplexity that is inherent in all consistent utilitarianism – which is the philosophy of homo faber par excellence – can be diagnosed theoretically as an inability to understand the distinction between utility and meaningfulness, between “in order to” and “for the sake of.” Thus, the ideal of usefulness that fills a society of craftsmen is no longer a matter of utility but of meaning. […] Obviously, there is no answer to the question which Lessing once put to the utilitarian philosophers of his time: “And what is the use of use?” The perplexity of utilitarianism is that it is caught in the never-ending chain of means and ends. It never arrives at some final principle which could justify the category of means-and-end, that is, of utility itself. The “in order to” has become the content of the “for the sake of.” In other words, utility, when it is established as meaning, creates meaninglessness.

[…] There is no way to end the chain of means-and-ends and prevent all ends from eventually becoming again means – except to declare that something is “an end in itself.” In the world of homo faber, where everything must be useful for something, an instrument to achieve something else, meaning can appear only as an end, an “end in itself.” This, actually, is either a tautology that applies to all ends, or a contradiction.

An end, once it is attained, stops being an end. It loses its ability to guide us and justify our choice of means, and how to organize and produce them. It has now become an object among objects. It has been added to the huge collection of things from which homo faber selects freely his means to pursue his ends. […] Homo faber, in so far as he thinks only in terms of means and ends, is unable to understand meaning, just as the animal laborans is unable to understand instrumentality. […]

The only way out of the dilemma of meaninglessness in utilitarian philosophy is to turn away from the objective world of use-things, and to rely on the subjectivity of use itself. Only in a strictly anthropocentric world, where the user – man himself – becomes the ultimate end which puts a stop to the never-ending chain of ends and means, can utility acquire the dignity of meaningfulness. Yet, the tragedy is that in the moment homo faber seems to find meaning in his own activity, he begins to degrade the world of things, the end and end-product of his own mind and hands. If man the user is the highest end, “the measure of all things,” then not only nature, which homo faber treats almost as “worthless material” to work with, but the “valuable” things themselves become mere means, losing their own intrinsic “value.”

[…]

If one permits the standards of homo faber to rule the finished world, then homo faber will eventually help himself to everything and consider everything as a mere means for himself. He will judge everything as if it belongs to the class of use-objects. To follow Plato’s example, the wind will no longer be understood in its own right as a natural force, but will be considered exclusively according to human needs for warmth or refreshment. Which, of course, means that the wind, as something objectively given, has been eliminated from human experience.

| 3. THINKING AS DISAPPEARING |

Hannah Arendt’s last book, The Life of the Mind, deals with philosophy of psychology, unlike most of her previous writings in the area of political philosophy. Nevertheless, this book is intimately connected to her previous interests, because it explores the psychological aspects of social reality as she envisioned it. Like her previous texts, it devotes much attention to ancient conceptions of the issue and how they developed through time.

Hannah Arendt’s last book, The Life of the Mind, deals with philosophy of psychology, unlike most of her previous writings in the area of political philosophy. Nevertheless, this book is intimately connected to her previous interests, because it explores the psychological aspects of social reality as she envisioned it. Like her previous texts, it devotes much attention to ancient conceptions of the issue and how they developed through time.

Arendt intended to divide the book into three parts, dealing with thinking, willing, and judging. These, according to her, are the three fundamental faculties of the mind. However, she died of a heart attack before completing the book, after finishing (more or less) only the first two parts.

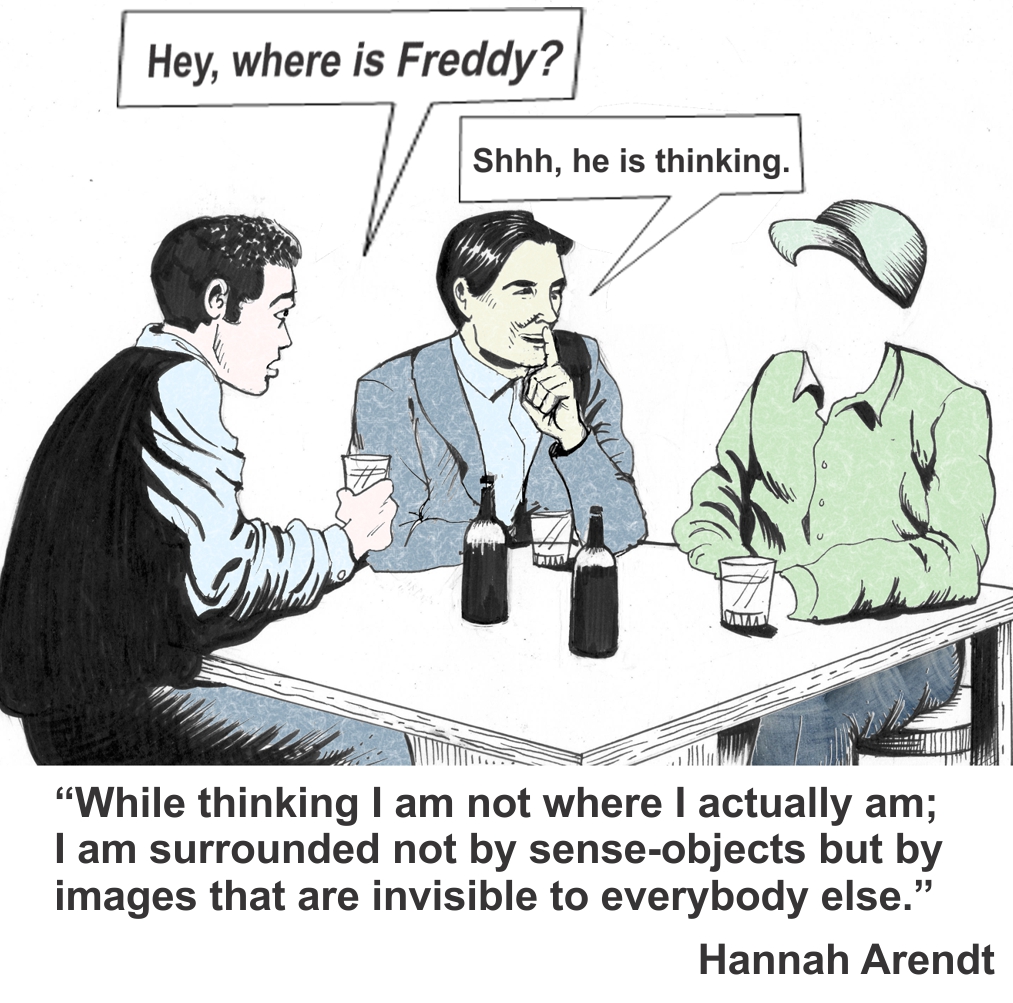

The following text is taken from Chapter 10 of the first part of her book, on thinking (slightly adapted for the ease of reading). Here she explains a central characteristic of thinking: When you think, you disconnect from your surroundings, even from your body. While thinking, you are “elsewhere.” Arendt connected this with the idea that philosophical thinking is like death, and also with the idea that the soul or mind is separate from body

To put it quite simply, in the familiar absent-mindedness of the philosopher, everything which is present is absent, because something that is actually absent is present to his mind; and among the things that are absent is the philosopher's own body. Both the philosopher's hostility toward politics – "the petty affairs of men," and his hostility toward the body […] are inherent in this experience. While you are thinking, you are unaware of your own corporality [=of your body] – and it is this experience that made Plato give immortality to the soul, once it has departed from the body. […]

Remembrance, the most frequent and also the most basic thinking experience, has to do with things that are absent, that have disappeared from my senses. Yet, what is absent and is summoned up and made present to my mind – a person, an event, a monument – cannot appear in the way it appeared to my senses, as a kind of witchcraft. In order to appear only to my mind, it must first be “de-sensed,” and the capacity to transform sense-objects into images is called "imagination." Without this faculty, which makes present what is absent in a de-sensed form, no thought processes and no trains of thought would be possible at all. Hence, thinking is "out of order" not merely because it stops all the other activities which are so necessary for the business of living and staying alive, but because it inverts all ordinary relationships: what is near and appears directly to our senses is now far away, and what is distant is actually present.

While thinking, I am not where I actually am. I am surrounded not by sense-objects, but by images that are invisible to everybody else. It is as if I had withdrawn into some never-never land, the land of invisibles, of which I would know nothing without this faculty of remembering and imagining. Thinking annihilates temporal as well as spatial distances. I can anticipate the future, I can think of it as though it was already present, and I can remember the past as though it had not disappeared.

[…]

Seen from the perspective of the immediacy of life and the world of the senses, thinking is, as Plato indicated, a living death. The philosopher who lives in the "land of thought" (Kant) will naturally be inclined to look upon these things from the viewpoint of the thinking ego, for which a life without meaning is a kind of living death. The thinking ego, because it is not identical with the real self, is unaware of its own withdrawal from the common world of appearances. From its perspective, it is as if the invisible came forward, as if the many entities that make up the world of appearances […] had been concealing an always-invisible Being that reveals itself only to the mind. In other words, what for common sense is the withdrawal of the mind from the world, appears in the mind's own perspective as a "withdrawal of Being" or "oblivion of Being"…

[…]

Thinking is also somehow self-destructive. […] Kant wrote: "I do not accept the rule that if pure reason has proved something, the result should no longer be subject to doubt, as though it were a solid axiom"; […] From which it follows that the business of thinking is like Penelope's web: it undoes every morning what it has finished the night before. Because the need to think can never be satisfied by allegedly definite insights of "wise men.” It can be satisfied only through thinking. And the thoughts which I had yesterday will satisfy this need today – only if I want and am able to think them anew.

[In summary,] We have been looking at the outstanding characteristics of the thinking activity: its withdrawal from the common-sense world of appearances; its self-destructive tendency regarding its own results; its reflexivity; and the awareness of sheer activity that accompanies it. Plus, the weird fact that I know about my mind's faculties only as long as the activity continues; which means that thinking can never be solidly established as a property – and even the highest property – of the human species: Man can be defined as the "speaking animal" (in the Aristotelian sense of being in possession of speech), but not as the thinking animal, the animal rationale.

| 4. THE MEANING OF FREEDOM |

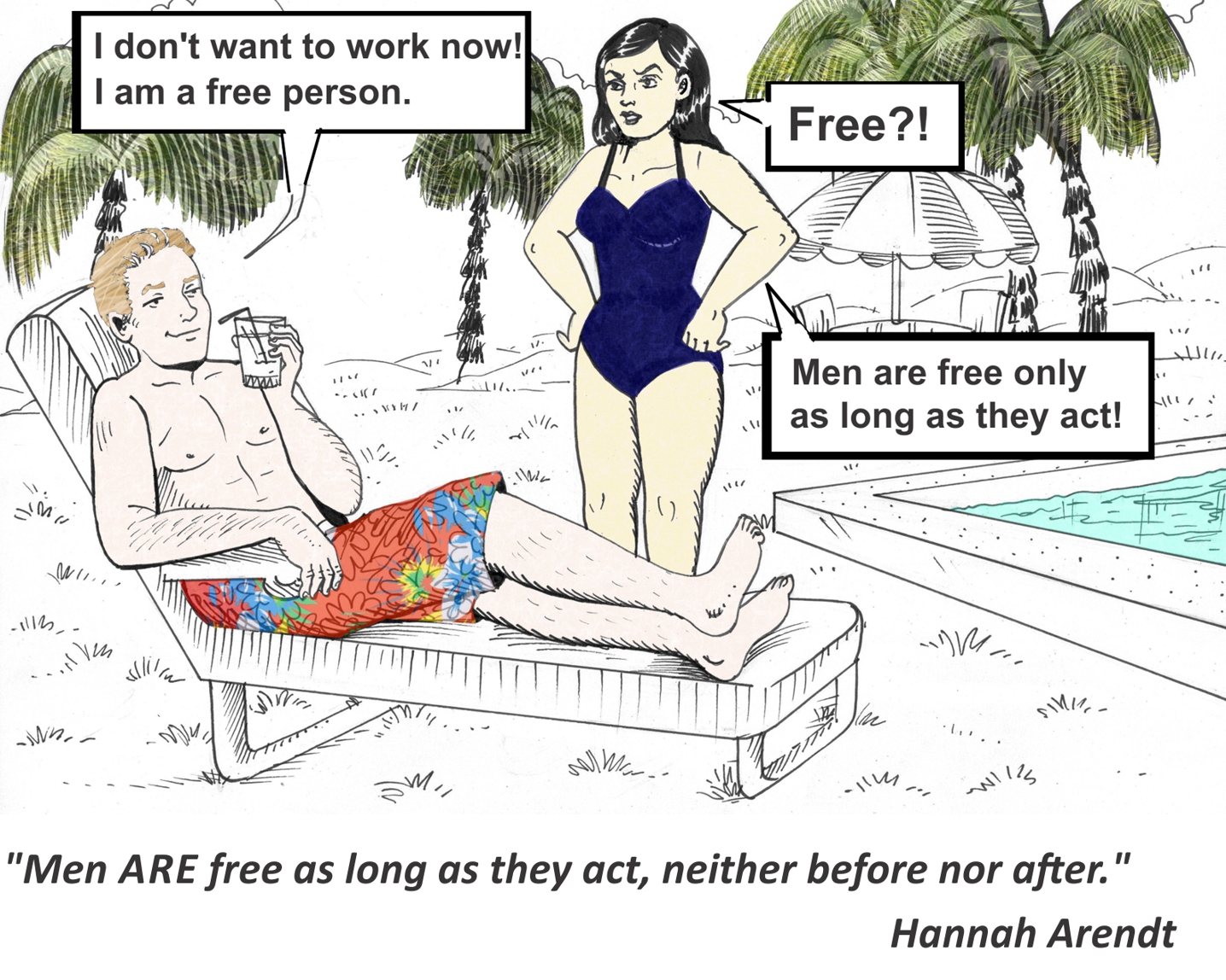

Freedom is a topic which Arendt discusses in several of her works. Nowadays we often speak about “inner freedom” or “freedom of the will” – your freedom to make up your mind and overcome psychological obstacles such as fear and hesitation. It is as if freedom is something inside you, between you and yourself. However, Arendt does not favor this approach to freedom. She argues that the “inner” notion of freedom is secondary, both historically and conceptually. The primary meaning of freedom is not hidden inside you but is expressed in your actions in society. To be free in his sense means that you act not out of necessity, not like a slave obeying his master, not in order to survive, not according to social norms or automatic routine. Rather, you initiate your own new action, you start something new, not dictated by previous conditions, in the context of a community. Historically, the idea of inner freedom was invented only when people could no longer find freedom in their society; the Stoics are a good example.

Freedom is a topic which Arendt discusses in several of her works. Nowadays we often speak about “inner freedom” or “freedom of the will” – your freedom to make up your mind and overcome psychological obstacles such as fear and hesitation. It is as if freedom is something inside you, between you and yourself. However, Arendt does not favor this approach to freedom. She argues that the “inner” notion of freedom is secondary, both historically and conceptually. The primary meaning of freedom is not hidden inside you but is expressed in your actions in society. To be free in his sense means that you act not out of necessity, not like a slave obeying his master, not in order to survive, not according to social norms or automatic routine. Rather, you initiate your own new action, you start something new, not dictated by previous conditions, in the context of a community. Historically, the idea of inner freedom was invented only when people could no longer find freedom in their society; the Stoics are a good example.

Thus, freedom in Arendt’s sense is not the freedom to choose between a banana and an apple. Nor is it the freedom to act out of personal motives, or towards a chosen aim. It is, rather, the freedom to initiate a new, unexpected action in the public realm.

The following text (slightly adapted for ease of reading) is taken from Part I and Part II of Arendt’s essay “What is Freedom?” which appeared in her book Between Past and Future, published in 1961.

From Part I

It seems safe to say that man would know nothing about inner freedom if he had not first experienced a condition of being free as a worldly, concrete reality. We first become aware of freedom or its opposite in our interaction with others, not in the interaction with ourselves. Before freedom became an attribute of thought or a quality of the will, it was understood to be the status of the free man, which enabled him to move, to get away from home, to go out into the world, and meet other people in actions and words.

[…] Without a politically guaranteed public realm, freedom lacks the worldly space to make its appearance. To be sure, it may still dwell in men's hearts as desire or will or hope or yearning; but the human heart, as we all know, is a very dark place, and whatever goes on in its obscurity can hardly be called a demonstrable fact. Freedom as a demonstrable fact and politics coincide, and they are related to each other like two sides of the same matter.

From Part II

Freedom, as related to politics, is not a phenomenon of the will. We deal here not with the liberum arbitrium – a freedom of choice that decides between two given things, one good and one evil […] Rather it is […] the freedom to bring something into existence which did not exist before, something which was not given, not even as an object of thought or imagination, and which therefore, strictly speaking, could not be known. Action, to be free, must be free from motive on one side, and from an intended goal as a predictable result on the other side. This is not to say that motives and aims are not important factors in every specific act, but they are its determining factors, and an action is free if it can transcend them.

Action, if it is determined, is guided by a future aim which the intellect has grasped as desirable, before the will wills it. The intellect then calls upon the will, since only the will can dictate action (to paraphrase Duns Scotus). The aim of action varies, depending on the changing circumstances of the world. To recognize the aim is not a matter of freedom, but of right or wrong judgment. Will, seen as a distinct and separate human faculty, follows judgment – in other words, it comes after recognizing the right aim, and it commands acting towards it. The power to command, to dictate action, is not a matter of freedom but a question of strength or weakness.

Action, if it is free, is neither under the guidance of the intellect nor under the dictate of the will, although it needs both of them in order to execute any particular goal. It comes from something completely different, which I will call a PRINCIPLE (following Montesquieu's famous analysis of forms of government). Principles do not operate from inside the self as motives do […] They inspire from the outside, as it were. And they are too general to prescribe particular aims, although every particular aim can be judged in the light of its principle once the act has been started. Because, unlike the judgment of the intellect which precedes action, and unlike the command of the will which initiates it, the inspiring principle becomes fully manifest only in the performing act itself. Yet, while a judgment may lose its validity, and the strength of the will may exhaust itself during the execution of the act, the principle which inspired the act loses nothing in strength or validity through execution. As opposed to its goal, the principle of an action can be repeated time and again. It is inexhaustible, and in contrast to its motive, the validity of a principle is universal. It is not tied to any particular person or to any particular group. However, principles are manifested only through action. They are manifest in the world as long as the action lasts, but no longer. Such principles are honor or glory, love of equality (which Montesquieu called virtue), or distinction or excellence (the Greek “always strive to do your best and to be the best of all"), but also fear or distrust or hatred. Freedom or its opposite appears in the world whenever such principles are actualized. The appearance of freedom, like the manifestation of principles, coincides with the performing act. Men ARE free (as opposed to possessing the gift for freedom) as long as they act, neither before nor after. Because to be free and to act are the same.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.