DEATH

Happiness

VIRTUE

THE OTHER PERSON

Inner Freedom

MUSIC

ROMANTIC LOVE

SEX

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. CONSCIOUSNESS IN CONSTANT CHANGE | 2. TIME AND THE SELF | ||

| 3. INTUITION AND INTELLECT | 4. AUTHENTICITY |

Henri Bergson (1859-1941) was an important French philosopher, extremely influential at the beginning of the 20th century, and a Nobel Prize winner in literature. He was born near Paris to a Jewish family, but as a teenager he lost his faith. He did his PhD in philosophy at the University of Paris, and his doctoral thesis was “Time and Free Will,” which became his first major book. His works on time, memory, biology, and other topics had a considerable impact on the intellectual circles of his time. He gave many lectures and communicated with major thinkers. After his retirement, in the 1930s, his popularity declined. He died in Paris of Bronchitis at the age of 81.

| 1. CONSCIOUSNESS IN CONSTANT CHANGE |

At the center of Bergson’s philosophy is the concept of DURATION. Duration is the way life flows through time. This is a holistic flow which constantly changes and develops in creative ways, and which cannot be analyzed into separate elements. We can see this most clearly in our consciousness: Our experiences of smell and of sounds, our sensations and emotions, our thoughts – these are not separate from each other. They penetrate into each other and “color” each other. For example, my smell-experience is not separate from my taste-experience, or from my headache, or from my anxiety. All of these qualities influence each other and interact and unify into one single complex “symphony.” Furthermore, this flow constantly changes in time, and it never remains the same. For instance, the first telephone ring which I hear and the second telephone ring are not the same in my experience, since each one had a different past: The first was an interruption, while the second was a continuity that resonated with the previous one. In this sense, the duration of consciousness is a flow that is always novel and creative, always creating new surprising combinations and qualities.

At the center of Bergson’s philosophy is the concept of DURATION. Duration is the way life flows through time. This is a holistic flow which constantly changes and develops in creative ways, and which cannot be analyzed into separate elements. We can see this most clearly in our consciousness: Our experiences of smell and of sounds, our sensations and emotions, our thoughts – these are not separate from each other. They penetrate into each other and “color” each other. For example, my smell-experience is not separate from my taste-experience, or from my headache, or from my anxiety. All of these qualities influence each other and interact and unify into one single complex “symphony.” Furthermore, this flow constantly changes in time, and it never remains the same. For instance, the first telephone ring which I hear and the second telephone ring are not the same in my experience, since each one had a different past: The first was an interruption, while the second was a continuity that resonated with the previous one. In this sense, the duration of consciousness is a flow that is always novel and creative, always creating new surprising combinations and qualities.

Duration characterizes the stream of consciousness, but it also characterizes living creatures, and the evolution of life on earth, and to some extent the life of entire universe. We can analyze the flow of life, but only approximately. For example, we can give names to feelings (“happiness,” “anxiety,” pain”) and in this way analyze the flow into separate elements. This analysis may be useful, especially for communicating in language, but it is not accurate, and it gives us a distorted idea that life is made of separate elements.

The following passages are taken (with light linguistic simplifications) from the beginning of his book Creative Evolution (1907).

From Chapter 1 of CREATIVE EVOLUTION

I find, first of all, that I pass from state to state. I am warm or cold, I am happy or sad, I work or I do nothing, I look at what is around me or I think about something else. Sensations, feelings, desires, ideas – these are the changes into which my existence is divided and which “color” it. I change, then, without stopping. But this is not saying enough. Change is much more radical than we tend to suppose at first.

Because I speak here about each one of my states as if it was a finished block and a separate whole. I say that I change, but as if the change resides only in the transition from one state to the next. When I look at each state separately, I tend to think that it remains the same during the time that it lasts.

However, a slight effort of attention would reveal to me that there is no feeling, no idea, no desire which is not undergoing change every moment. If a mental state stopped changing, its duration would stop to flow. […] My mental state, as it advances on the road of time, is continually swelling with the DURATION which it accumulates: It continues increasing, rolling upon itself, like a snowball on the snow. This is especially so with psychic states that are more deeply internal, such as sensations, feelings, desires, etc. which do not correspond to an external object, as in the case of a visual perception. But it is convenient to ignore this uninterrupted change, and to notice it only when it is big enough to produce a new attitude in our body, to direct our attention in a new direction. Then, and only then, we find that our state has changed. The truth is that we change without stopping, and that the state itself is nothing but change.

This amounts to saying that there is no essential difference between passing from one state to another and continuing in the same state. If the state which "remains the same" is more varied than we think, then the passing from one state to another resembles a single state that is prolonged; the transition is continuous. But, since we ignore the continuous changes of every psychic state, we are forced to speak as if a new state appeared next to the previous one, when the change has become so great that it forces itself on our attention. And we assume that this new state remains unchanging too, and so on endlessly.

The apparent discontinuity of the psychic life is, therefore, a result of the fact that our attention is composed of a series of separate acts of attention. As a matter of fact, there is only a gentle slope. But when we follow the broken line of our acts of attention, we think that we perceive separate experiences. True, our psychic life is full of unforeseen events. A thousand incidents arise, which seem to be disconnected from the previous ones, and from the next ones. However, although they appear discontinuous, in fact they appear against the background of the continuity that produces them, and to which they owe the intervals that separate them. They are the drum-beats which sound here and there in the symphony. Our attention fixes on them because they interest us more, but each of them is born from the fluid mass of our whole psychic existence.

[…]

Our duration is not just one moment that replaces another moment. If this was so, there would never be anything except for the present moment – no flow of the past into the present, no evolution, no concrete duration. Duration is the continuous progress of the past which gnaws into the future and which swells as it advances. And as the past grows without stopping, so also there is no limit to how much it remains in us. […]

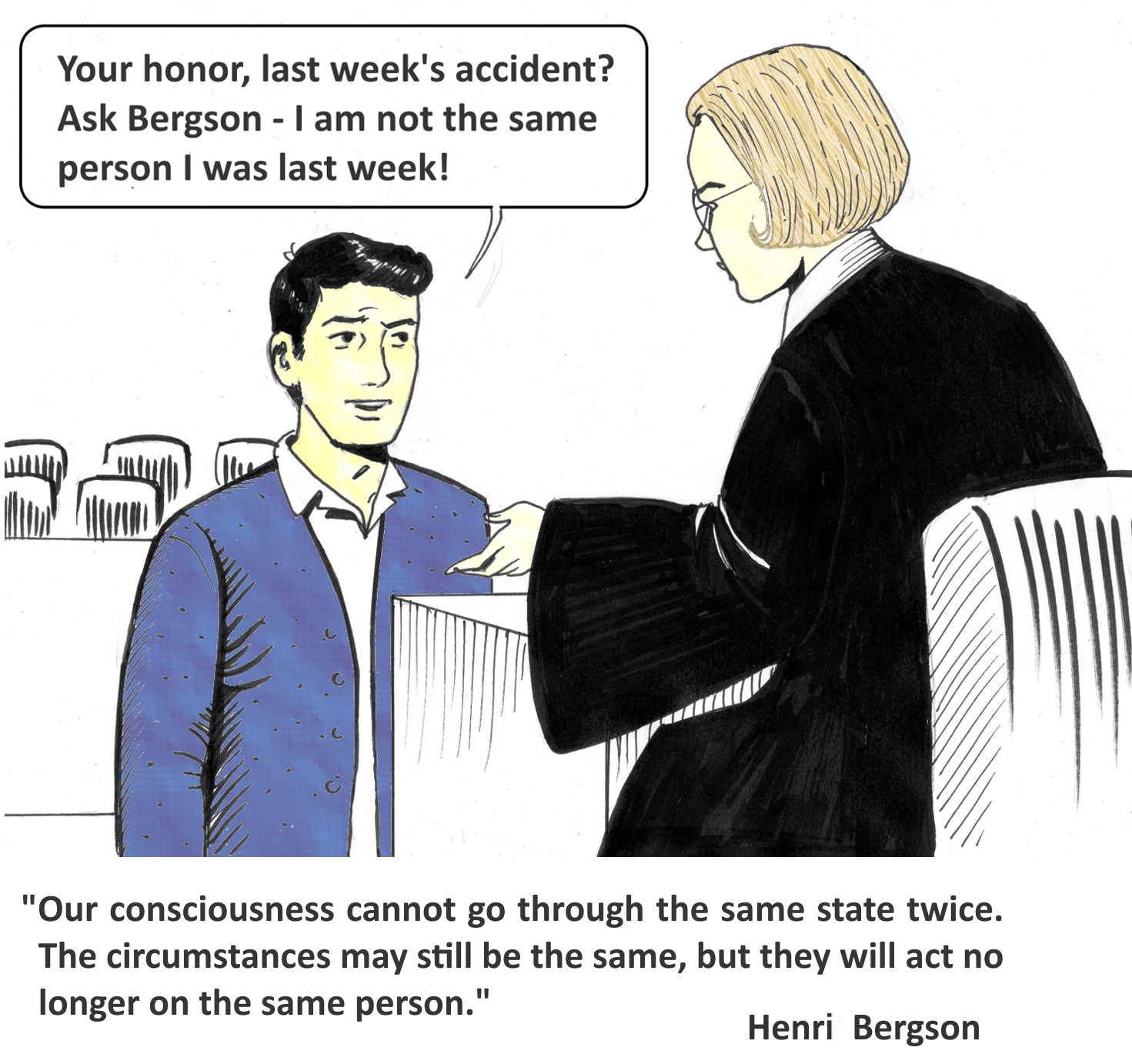

From this survival of the past it follows that consciousness cannot go through the same state twice. The circumstances may still be the same, but they will no longer act on the same person, since they find him at a new moment of his history. Our personality, which is being built up each moment with its accumulated experience, changes without stopping. By changing, it prevents any state, even if it seems the same as another, from ever repeating exactly. That is why our duration is irreversible. We could not live again a single moment, because we would have to erase the memory of everything that had followed that moment. Even if we could erase this memory from our intellect, we could not erase it from our will.

Thus, our personality is born, grows and matures without stopping. Each of its moments is something new that is added to what was before. Furthermore, it is not only something new, but something that cannot be foreseen.

| 2. TIME AND THE SELF |

The nature of time is at the center of Bergson’s philosophy. We often think about time as an abstract dimension (a “homogenous medium,” as he calls it). This kind of time, Bergson notes, behaves like a “space” – a space-like dimension which contains specific events that are located in specific locations. Bergson agrees that this is an accurate representation of time for inanimate physical objects.

But for our consciousness, time is something very different. Our feelings and emotions and thoughts are not separate items that occupy precise intervals on the time-dimension, and that extend for X number of seconds. They never remain the same even for an instant, and they are not separate from each other. Rather, they penetrate each other and color each other without clear boundaries, always creating new combinations and new qualities. They form a creative flow of qualities that cannot be analyzed into separate items with “the same” quality, or with specific boundaries and locations. Thus, for consciousness time is not an abstract dimension of points, but DURATION: a holistic flow of qualities.

The following passages are adapted (with some linguistic simplifications) from Bergson’s first main book, Time and Free Will (1889). In this book he focuses on consciousness, and he distinguishes between its real flow and its abstract representation as a dimension, in other words between real duration and geometric time. The former is real, while the second is an abstraction, a projection, a shadow of real duration. (In later books he will apply the same distinction to memory, biology, evolution, humor, religion, and other phenomena.) The main reason why we to cut up duration and represent it as an abstract dimension of moments is language. In order to communicate with others, we must use general words that are blind to the infinite complexity of real conscious moments. The result of this duality is that our self has two sides: The surface of the self is made of a sequence of discrete mental objects in abstract time, while the depth of the self is a rich, holistic flow of qualities that merge into each other.

From Chapter 2

Let us notice that when we speak about time, we generally think of a homogeneous medium [=abstract dimension] in which our conscious states are arranged one after the other like in space, in the form of discrete multiplicity. […] Does the multiplicity of our conscious states have the slightest similarity to the multiplicity of the units of a number? Has true duration anything to do with space? Our analysis of the idea of number would certainly make us doubt this analogy.

[…]

When we hear a series of blows of a hammer, the sounds produce one indivisible melody, a dynamic progress. But since we know that the same objective cause [=the hammer] is operating again and again, we cut the progress of our consciousness into phases, and we then regard them as “the same.” And this multiplicity of “the same” elements, which we are now forced to see as placed next to each other in a kind of space, leads us necessarily to the idea of a homogeneous time, which in fact is the symbolical image of real duration. In short, our ego comes in contact with the external world at its surface; the series of our sensations, although they dissolve into one another, keep some of the mutual externality [=separateness] which belongs to the hammer that caused them. And so, we naturally picture our superficial psychic life as if it is spread in a homogeneous medium [=along an abstract dimension].

[…]

We should therefore distinguish two forms of multiplicity, two very different ways of looking at duration, two aspects of conscious life. Below homogeneous time, which is the space-like symbol of true duration, a careful reflection would notice a duration whose heterogeneous moments penetrate each other. Below the numerical multiplicity of conscious states, there is a qualitative multiplicity. Below the self with well-defined states, there is a self in which the moments that follow each other melt into each other and form an organic whole. But we are usually content with the first, with the shadow of the self as it is projected into homogeneous space. Consciousness, forced by our desire to separate, substitutes the symbol for the reality, or perceives the reality only through the symbol. Since the self, when it is broken to pieces, is much more convenient for the requirements of social life, particularly for language, consciousness prefers it, and it gradually loses sight of the fundamental self.

[…] Yet this difference escapes the attention of most of us. We hardly perceive it, unless we are warned about it and then we carefully look into ourselves. The reason is that our outer social life is more practically important to us than our inner and individual existence. We instinctively tend to solidify our feelings in order to express them in language. Hence, we confuse the feeling itself – which is constantly changing, with its stable external object, and especially with the word which refers to it.

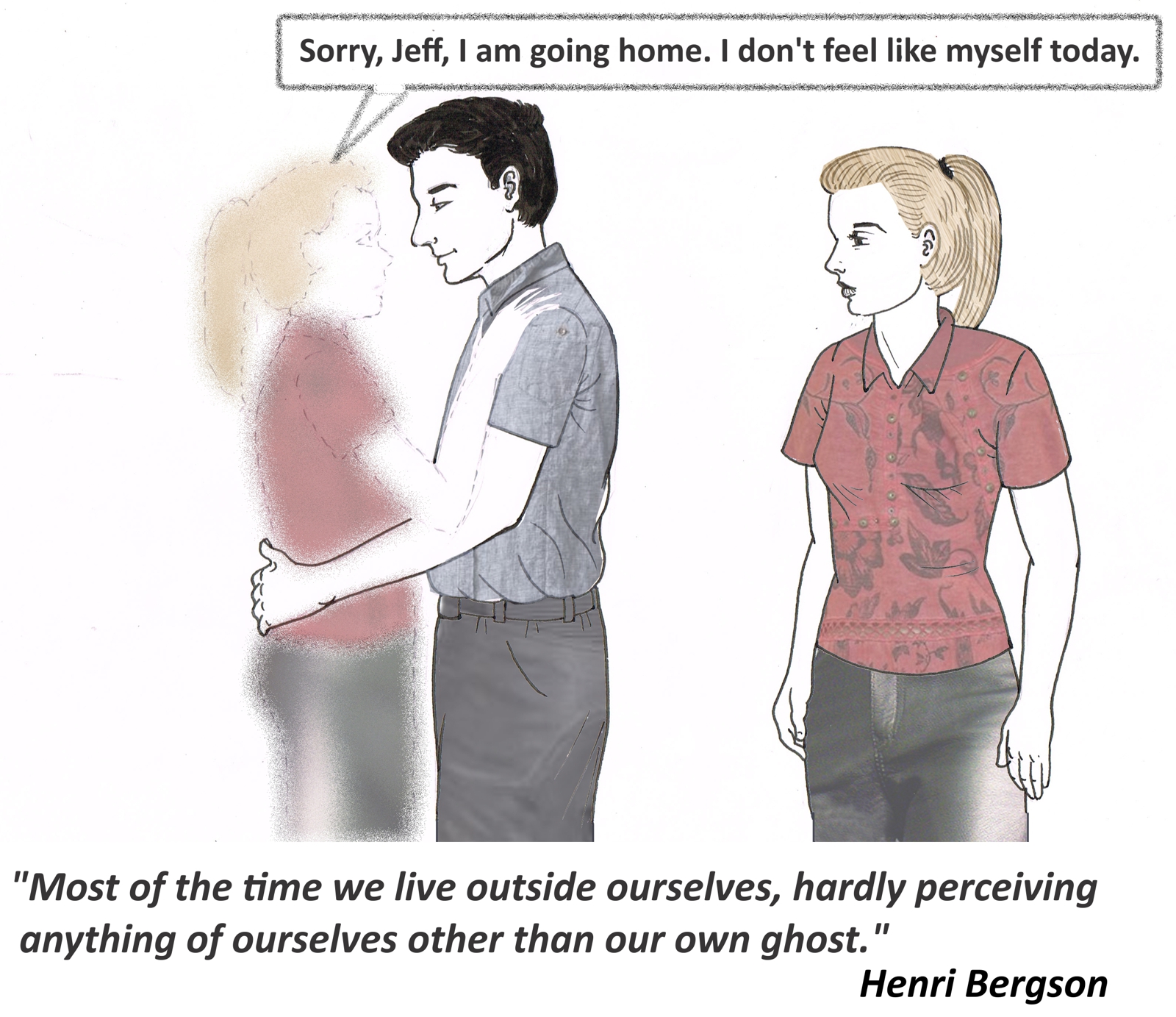

FROM THE “CONCLUSION” CHAPTER

Thus, there are two different selves, one self which is the external projection of the other self, its spatial and social representation. We reach the latter self by deep introspection, which leads us to grasp our inner states as living things, constantly developing. These are inner states which cannot be measured, which penetrate each other, a flow of duration which has nothing in common with a sequence of separate elements that follow one other in an abstract homogeneous space. But the moments in which we grasp ourselves like that are rare, and this is just why we are rarely free. Most of the time we live outside ourselves, hardly perceiving anything of ourselves other than our own ghost, a colorless shadow which pure duration projects into homogeneous space. As a result, our life unfolds in space rather than in real time [duration]. We live for the external world rather than for ourselves, we speak rather than reflect; we “are acted” rather than act ourselves. To act freely is to re-possess oneself, and to get back into pure duration.

| 3. INTUITION AND INTELLECT |

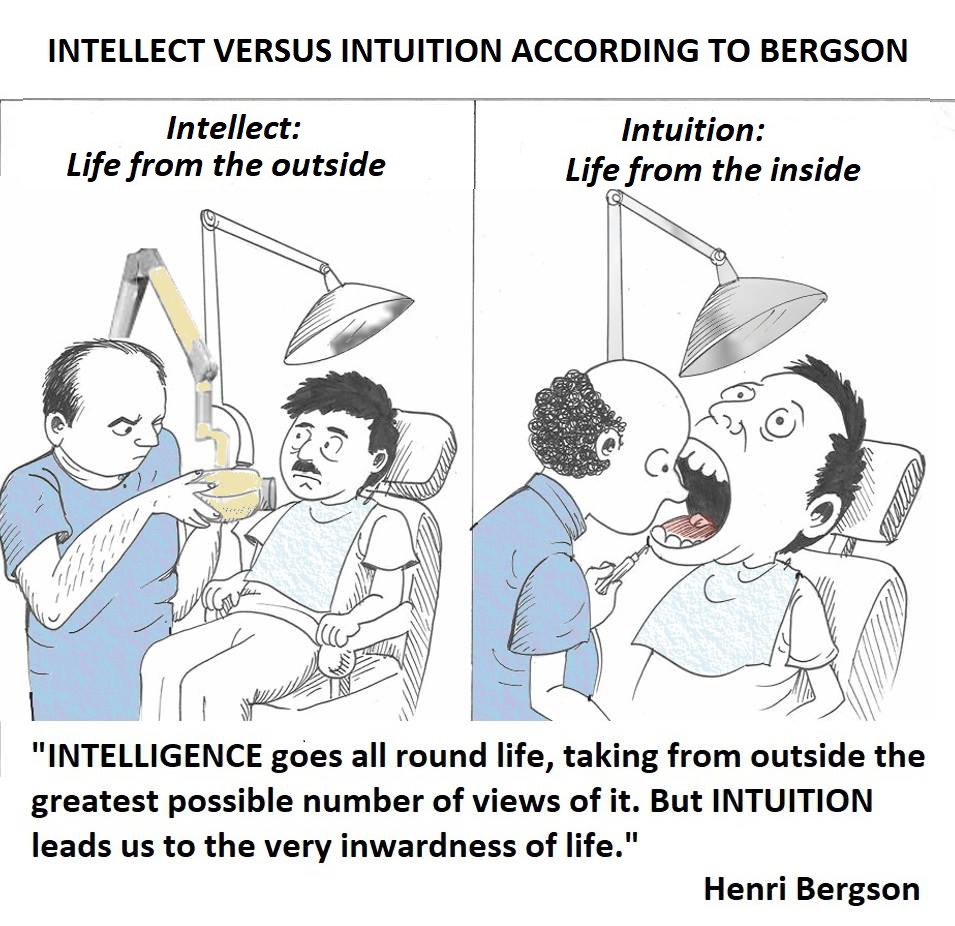

Central to Bergson’s philosophy is the distinction between “intuition” and “intellect,” which are two very different ways of understanding. Intuition is our way to understand the whole, while the intellect is our way to understand through analysis. With intuition we perceive duration – the holistic and creative flow of consciousness, and of life in general. This is because intuition grasps the whole without concepts and without divisions. In contrast, our intellect (also called “intelligence”) analyzes the whole into parts, applying to it distinctions and concepts and measurements. In this respect, Bergson explains, with the intellect we understand an object from the outside – by thinking about it, while in intuition we understand a living being from the inside, through what Bergson calls “sympathy” – which is a direct connection to life. The advantage of the intellect is that it produces precise results which can be replicated, verified, described, and communicated in language. Yet, when the intellect looks at life, it fails to grasp its flow. Its conceptual and analytic tools can understand life only by approximation and abstraction. Therefore, intellect and intuition are two very different ways of understanding – one is best for science, while the other is best for understanding life.

Central to Bergson’s philosophy is the distinction between “intuition” and “intellect,” which are two very different ways of understanding. Intuition is our way to understand the whole, while the intellect is our way to understand through analysis. With intuition we perceive duration – the holistic and creative flow of consciousness, and of life in general. This is because intuition grasps the whole without concepts and without divisions. In contrast, our intellect (also called “intelligence”) analyzes the whole into parts, applying to it distinctions and concepts and measurements. In this respect, Bergson explains, with the intellect we understand an object from the outside – by thinking about it, while in intuition we understand a living being from the inside, through what Bergson calls “sympathy” – which is a direct connection to life. The advantage of the intellect is that it produces precise results which can be replicated, verified, described, and communicated in language. Yet, when the intellect looks at life, it fails to grasp its flow. Its conceptual and analytic tools can understand life only by approximation and abstraction. Therefore, intellect and intuition are two very different ways of understanding – one is best for science, while the other is best for understanding life.

From INTRODUCTION TO METAPHYSICS (1903)

In this essay, published in 1903, Bergson gives the clearest explanation of what he means by “intuition.” He argues that while science investigates through our intellectual capacity, the study of consciousness belongs to philosophy, which can use the intuition.

By intuition I mean the kind of intellectual sympathy by which we place ourselves within an object, in order to coincide with what is unique in it, and therefore inexpressible. Analysis, on the contrary, is the operation which reduces the object to elements that are already known, that is, to elements which are common to it and to other objects. To analyze, therefore, is to express a thing as a function of something other than itself. Every analysis is thus a translation, a development into symbols, a representation taken from successive points of view from which we note as many similarities as possible between the new object which we are studying, and other objects which we believe we know already. Analysis, with its always-unsatisfied desire to embrace the object, is forced to turn around it, and to multiply endlessly the number of its points of view in order to complete its representation which is never complete, and to keep changing its symbols in order to perfect the always-imperfect translation. It goes on, therefore, to infinity. But intuition, if intuition is possible, is a simple act.

There is one reality, at least, which we all capture from the inside, by intuition and not by analysis. It is our own personality as it flows through time - our self which endures [=flows in duration]. We may sympathize intellectually with nothing else, but we certainly sympathize with our own selves. When I direct my attention inward to contemplate my own self, I first perceive, as a crust that is solidified on the surface, all the perceptions which come from the material world. These perceptions are clear, distinct, one next to each other. They tend to group themselves into objects. […] Underneath these sharply cut crystals and this frozen surface, there is a continuous flow which cannot be compared to any flow I have ever seen. There is a succession of states, each one announcing what will follow, each one containing what came before it. Only afterwards I can say that these states were many, when I look back to observe their path. While I was experiencing them, they were so solidly organized, so profoundly animated with a common life, that it was impossible to say where one of them ended or where another began. In reality, none of them begins or ends, but they all extend into each other.

From CREATIVE EVOLUTION (1907)

After explaining in detail the idea of “duration” in his book TIME AND FREE WILL (1889), Bergson applied this idea to the phenomenon of memory (MATTER AND MEMORY, 1896), then to humor (LAUGHTER, 1900). Then, in 1907, he published his most influential book (CREATIVE EVOLUTION), which applied the idea of duration to the evolution of life on earth. Life, he argued, is a flow of duration energized by a creative impulse, a “river of life” that started millions of years ago and continuously develops in complexity and sophistication. However, this river of life is not one single flow. Throughout the history of evolution, it divided itself into different streams – plants, insects, mammals and humans – which represent different strategies to survive and grow and develop. Insects, for example, use the instinct – the capacity to relate to other living being directly, without concepts, through “sympathy” (even when they attack them to eat them). Higher animals have the capacity to distinguish and analyze, namely the intellect. Finally, humans also have intuition, which is an instinct (“sympathy” with life) that has become self-aware, so that it not only relates to life directly, but also understands life directly, from the inside.

The following passage is adapted from Chapter 3 of CREATIVE EVOLUTION, entitled “The divergent directions of the evolution of life – torpor, intelligence, instinct.” Here Bergson suggests that we can develop an entire philosophy that is based on intuition. Just as science uses the intellect to investigate dead matter, philosophy of life should use intuition to investigate life.

Instinct is sympathy. […] Intelligence and instinct are turned in opposite directions, the former towards inanimate matter, the latter towards life. INTELLIGENCE, through science (which is its work), will give us more and more completely the secret of physical activities […] It goes around life, taking from outside the greatest possible number of views of it, pulling life into itself instead of entering into it. But INTUITION leads us to the very inwardness of life – by intuition I mean instinct that has become disinterested, self-conscious, capable of reflecting on its object and enlarging it indefinitely.

That this kind of effort is possible, is proved by the fact that we have an aesthetic faculty in addition to normal perception. Our eye perceives the properties of a living being as if they were a collection of different elements side by side, not as an organized whole. What escapes the eye is the intention of life, the simple movement that runs through the lines, that connects them together and gives them meaning. This intention is exactly what the artist tries to regain, by placing himself back inside the object through a kind of sympathy. And by the effort of intuition, he breaks down the barrier which space places between him and his model.

It is true that this aesthetic intuition, like external perception, relates only to SPECIFIC individual beings. But we can think of an inquiry that has the same orientation as art – which investigates life IN GENERAL, just like physical science, and turns individual facts into general laws. Certainly, this kind of philosophy will never achieve a knowledge that is comparable to the knowledge which science has of its own objects. Intelligence remains the luminous nucleus around which instinct, even when it is enlarged and purified into intuition, forms only a vague nebula. But, given the incompleteness of intelligent knowledge, intuition may enable us to grasp what intelligence fails to give us, and to indicate the way to complete it.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.