LIST OF PHILOSOPHERS

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. REVERENCE FOR LIFE | 2. THE WILL TO LIVE | 3.THE SOCIAL MISSION OF PHILOSOPHY |

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) was a French-German thinker, theologian, musician, and medical doctor, who became famous for his humanitarian activities in West Africa. He was born in Alsace, which at that time belonged to Germany (but returned to France after World War I). He wrote his PhD thesis at the Sorbonne University, Paris, on the religious philosophy of Kant. At the same time he gained fame as a musician – an organist with primary interest in Bach. When he was 30 years old, he started studying medicine, feeling that this was his true call. Eight years later, in 1913, after becoming a medical doctor, he moved with his wife to West Africa. His wife, Helene Bresslau Schweitzer, born to a Jewish family but converted as a child, was herself a special person, devoted to helping others. In a remote jungle area in West Africa, in present-day Gabon (a French colony at that time), the Schweitzers established a hospital for local people. He later moved back and forth between Africa and Europe, received many honors including the Nobel Prize, and died in Gabon in the hospital which he had founded.

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965) was a French-German thinker, theologian, musician, and medical doctor, who became famous for his humanitarian activities in West Africa. He was born in Alsace, which at that time belonged to Germany (but returned to France after World War I). He wrote his PhD thesis at the Sorbonne University, Paris, on the religious philosophy of Kant. At the same time he gained fame as a musician – an organist with primary interest in Bach. When he was 30 years old, he started studying medicine, feeling that this was his true call. Eight years later, in 1913, after becoming a medical doctor, he moved with his wife to West Africa. His wife, Helene Bresslau Schweitzer, born to a Jewish family but converted as a child, was herself a special person, devoted to helping others. In a remote jungle area in West Africa, in present-day Gabon (a French colony at that time), the Schweitzers established a hospital for local people. He later moved back and forth between Africa and Europe, received many honors including the Nobel Prize, and died in Gabon in the hospital which he had founded.

|

TOPIC 1. REVERENCE FOR LIFE |

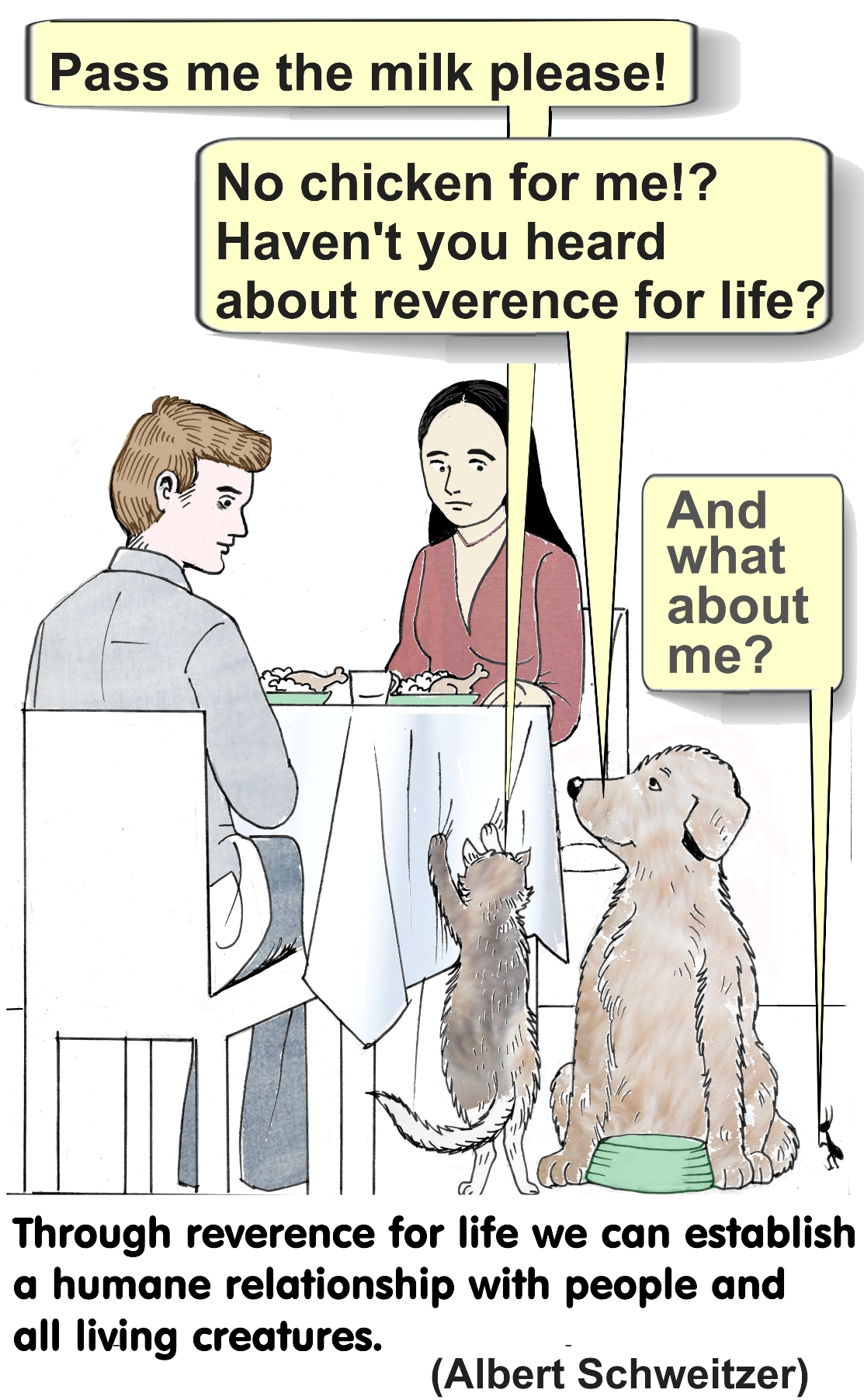

“Reverence for life” is probably Schweitzer's best-known philosophical concept. Although he wrote on a variety of topics, ethics was at the center of his thought. He was unsatisfied with existing systems of ethics, and felt that a new ethical system was needed to guide our lives and prevent the decay of our civilization. For years he searched for a new basis for ethics, until he came up with the concept of “reverence for life,” which he developed in his writings and followed in his humanitarian activities. In 1952 he received the Nobel Prize for his writings on the philosophy of reverence for life. The following passages are from the book ALBERT SCHWEITZER SPEAK OUT (1964).

“Reverence for life” is probably Schweitzer's best-known philosophical concept. Although he wrote on a variety of topics, ethics was at the center of his thought. He was unsatisfied with existing systems of ethics, and felt that a new ethical system was needed to guide our lives and prevent the decay of our civilization. For years he searched for a new basis for ethics, until he came up with the concept of “reverence for life,” which he developed in his writings and followed in his humanitarian activities. In 1952 he received the Nobel Prize for his writings on the philosophy of reverence for life. The following passages are from the book ALBERT SCHWEITZER SPEAK OUT (1964).

At sunset of the third day, near the village of Igendja, we moved along an island set in the middle of the wide river. On a sandbank to our left, four hippopotamuses and their young slowly walked in our same direction. Just then, in my great tiredness and discouragement, the phrase “Reverence for Life” struck me like a flash. As far as I knew, it was a phrase I had never heard nor even read. I realized at once that it carried within itself the solution to the problem that had been torturing me. Now I knew that a system of values which deals only with our relationship to other people is incomplete, and therefore lacking in power to do good. Only through reverence for life can we establish a spiritual and humane relationship with both people and all living creatures within our reach. Only in this way can we avoid harming others, and, within the limits of our capacity, go to their aid whenever they need us.

It also became clear to me that this basic but complete system of values had a completely different depth and an entirely different vitality than a system that was concerned only with human beings. Through reverence for life, we come into a spiritual relationship with the universe. The inner depth of feeling, which we experience through it, gives us the will and the ability to create a spiritual and ethical set of values that enables us to act on a higher level, because we then feel ourselves truly at home in our world. Through reverence for life we become, in effect, different persons.

[…]

The fundamental fact of human awareness is this: “I am life that wants to live in the midst of other life that wants to live.” A thinking person feels forced to approach all life with the same reverence he has for his own life. Thus, all life becomes part of his own experience. From such a point of view, “good” means to maintain life, to further life, to bring developing life to its highest value. “Evil” means to destroy life, to hurt life, to keep life from development. This, then, is the rational, universal, and basic principle of ethics.

Ethics until now had been incomplete because its main concern was merely with the relationship of man to man. In reality, however, ethics must also be concerned with the way man behaves toward all life. In essence, then, a person can be considered ethical only if life as such is sacred to him – both in people, and in all creatures that inhabit the earth.

The actual living of this ethic, with its responsibilities extending toward all living things, is deeply rooted in universal thought. The ethical relationship of man to man is not something that stands by itself, but is part of a greater concept. The idea of reverence for life contains everything that expresses love, submission, compassion, the sharing of joy, and common striving for the good of all. We must free ourselves from thoughtless existence.

At the same time, we are all subject to the mysterious and cruel law by which we maintain human life at the cost of other life. Through this destruction and harm of other life we develop feelings of guilt. As ethical human beings we must constantly strive to escape from this need to destroy – as much as we possibly can. We must try to demonstrate the essential worth of life by doing all we can to alleviate suffering. Reverence for life, which grows out of a proper understanding of the will to live, contains life-affirmation. It acts to create values that serve the material, the spiritual, and ethical development of the human being.

|

TOPIC 2. THE WILL TO LIVE |

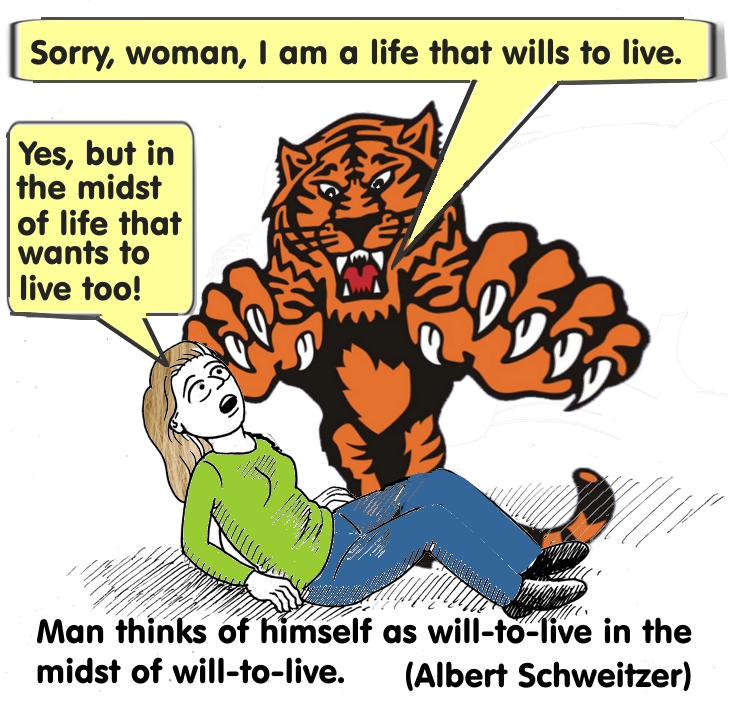

Another important concept in Schweitzer’s thought is “The Will to Live.” It is the foundation of the concept of Reverence for Life. The following text is from Schweitzer’s text OUT OF MY LIFE AND THOUGHT (1931).

Another important concept in Schweitzer’s thought is “The Will to Live.” It is the foundation of the concept of Reverence for Life. The following text is from Schweitzer’s text OUT OF MY LIFE AND THOUGHT (1931).

The most immediate fact of man’s consciousness is the assertion: “I am life which wills to live, in the midst of life which wills to live.” And man thinks of himself like that – as will-to-live in the midst of will-to-live – during every moment in which he reflects on himself and the world around him.

In the case of my own will-to-live, I have a passionate desire for advancing life and for the mysterious exhilaration of the will-to-live which we call pleasure, and a fear of destruction and of that mysterious reduction of the will-to-live which we call pain. In the same way, these things also exist in the will-to-live around me, whether it can express itself to me, or remains quiet.

Man has to decide what will be his relation to his will-to-live. He can deny it. But if he wants his will-to-live to change into will-not-to-live, as in Indian and indeed in all pessimistic thought, then he involves himself in self-contradiction. He elevates something unnatural to the position of his philosophy of life, something which is untrue, and which cannot be completely realized. […] Negation of the will-to-live is consistent only if you really want to put an end to your physical existence.

If man affirms his will-to-live, then he acts naturally and honestly. He confirms an act which already exists in his instinctive thought by repeating it in his conscious thought. The beginning of thought, a beginning which continually repeats itself, is that man does not simply accept his existence as something given, but experiences it as something unfathomably mysterious. Affirmation of life is the spiritual act by which man stops living unreflectively and begins to devote himself to this life with reverence, in order to raise it to its true value. To affirm life is to deepen the will-to-live, to make it more inward, and to elevate it.

At the same time, the man who has become a thinking being feels a compulsion to give to every will-to-live the same reverence to life that he gives to his own. He experiences this other life in his own life. He accepts that it is good to preserves life, to promote life, to raise any life that can develop to its highest value. And he accepts that it is evil to destroy life, to injure life, to repress life which is capable of development. This is the absolute, fundamental principle of morality, and it is a necessity of thought.

The great fault of all ethical systems so far is that they believed that they had to deal only with the relations of man to man. In reality, however, the question is what is man’s attitude to the world and to all life that comes within his reach. A man is ethical only when life in general is sacred to him, the life of plants and animals like that of his fellow human beings, and when he devotes himself to helping all life that needs his help. […]

The world, however, offers us the horrible drama of the Will-to-Live divided against itself. The existence of one life is at the cost of another life; one destroys another. Only in the thinking person, the Will-to-Live become conscious of another will-to-live, and wants solidarity with it. This solidarity, however, he cannot realize completely, because man is subject to the puzzling and horrible law of being forced to live at the expense of another life, and to suffer again and again the guilt of destroying and injuring life. But as an ethical being, he strives to escape this necessity whenever possible. And as somebody who is enlightened and merciful, he strives to end this contradiction of the Will-to-Lie as far as he can. He thirsts to preserve his humanity, and to be able to free other existences from suffering.

Reverence for Life which comes from the Will-to-Live that has become reflective, therefore contains affirmation of life and ethics inseparably combined.

|

TOPIC 3. THE SOCIAL MISSION OF PHILOSOPHY |

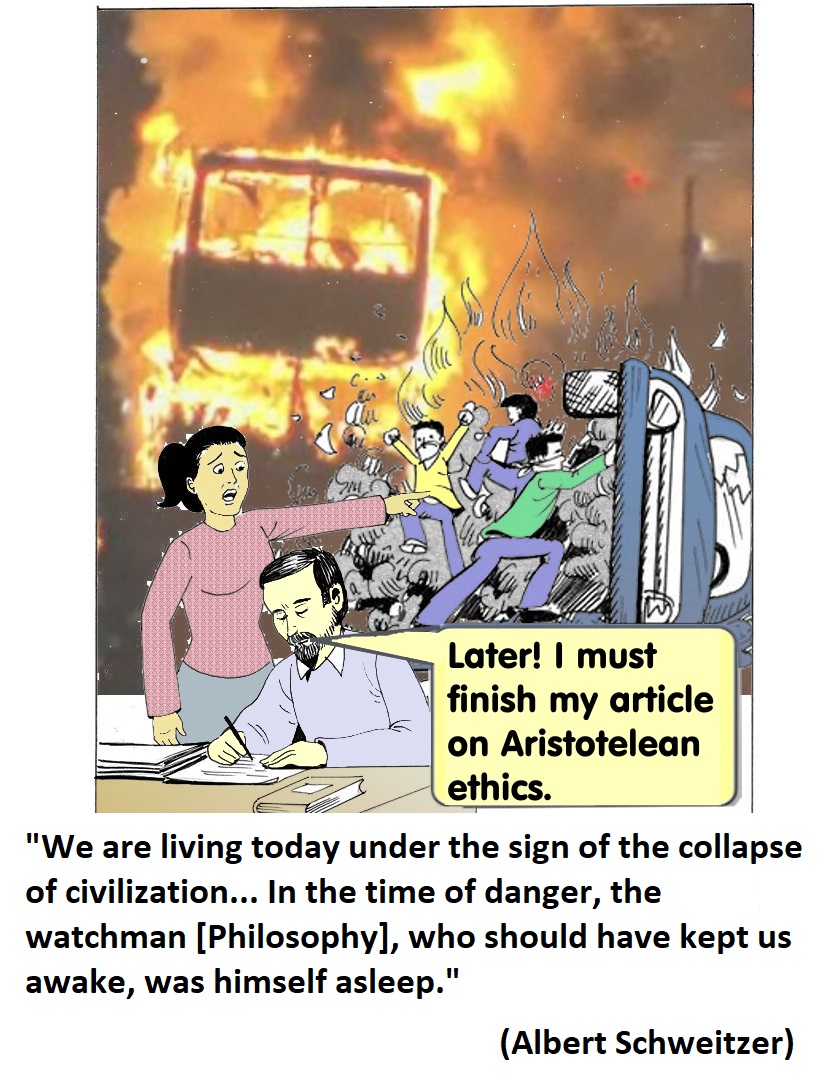

Albert Schweitzer was very critical of contemporary society. In his book THE PHILOSOPHY OF CIVILIZATION (1923), he described the spiritual emptiness of modern times, after the collapse of Rationalism in the 19th century. He suggested that philosophy had the duty to deal with the collapse of the old values, but it did nothing.

Schweitzer did not think that philosophy can offer a new metaphysical foundation for ethics, or even for knowledge of the world, but that philosophy should confess that it is unable to do so. This would tell us that we should search elsewhere, and would give us an important insight: ethics is not founded on our knowledge of the world, but on our awareness of the Reverence for Life, which must be the starting point for philosophical ethics.

The following is slightly adapted from Schweitzer’s book, Volume 1: “The Decay and Restoration of Civilization.”

From the INTRODUCTION

From the INTRODUCTION

The future of civilization depends on our overcoming the meaninglessness and hopelessness which characterize the thoughts and convictions of people today, and reaching a state of fresh hope and fresh determination. We will be capable of this, however, only when most people will discover for themselves both an ethic, and a profound and committed attitude of world- and life-affirmation, in a theory of the universe which is both convincing and based on reflection. Without such a general spiritual experience, there is no possibility of stopping our world from the ruin and disintegration which it is quickly approaching. It is our duty, then, to elevate ourselves to fresh reflection about the world and life.

From CHAPTER 1

We are living today under the sign of the collapse of civilization. The situation has not been produced by the war; the war is only a manifestation of it. The spiritual atmosphere has solidified into actual facts which influence it with disastrous results in every respect. […] We have drifted out of the stream of civilization because there was among us no real reflection on what civilization is. […] Philosophy, in spite of all her learning, became a stranger to the world, and the problems of life which occupied people and the whole thought of the period had no part in her activities. She separated from the general spiritual life, and just as she received no stimulus from it, so she gave none back. While refusing to deal with basic issues, she contained no basic philosophy which could become a philosophy of the people.

From this impotence came her dislike for all the philosophizing that is understandable to the general population. Popular philosophy was for her just a display, prepared for the use of the crowd, simplified, and therefore regarded as inferior […] She was completely unconscious of several things – that there is a popular philosophy which arises out of such a display; that it is the province of philosophy to deal with basic, inward questions which individuals and the crowd are thinking, or should be thinking, […] and, finally, that the value of any philosophy depends on its ability or inability to transform itself into a living philosophy of the people.

[…] The fact that pure thought never managed to construct a theory of the universe of an optimistic and ethical character, and to build upon this foundation the ideals which produce civilization – this was not the fault of philosophy, but was a fact which became evident as thought developed. But philosophy was guilty of not admitting this fact, and instead it remained wrapped up in its illusion, as if this was really a help to the progress of civilization.

The ultimate mission of philosophy is to be the guide and guardian of the general reason. And it was her duty, in the circumstances of the time, to confess to our world that ethical ideals were no longer supported by any general theory of the universe, but were left to themselves, till further notice, and had to make their way in the world by their own power. She should have shown us that we have to fight for the ideals on which our civilization rests. She should have tried to give these ideals an independent existence based on their own inner value and inner truth, and so to keep them alive and active without any help from a theory of the universe. Every effort should have been made to direct the attention of people, cultured and the uncultured alike, to the problem of the ideals of civilization.

But philosophy philosophized about everything except civilization. […] So little did philosophy philosophize about civilization that she did not even notice that she herself, and the historical age together with her, were losing more and more of it. In the time of danger, the watchman, who should have kept us awake, was himself asleep, and the result was that we put up no fight at all on behalf of our civilization.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.