The Philo-Practice Agora

The electronic library for philosophical practitioners from around the world

LIST OF PHILOSOPHERS

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. SOLITUDE | 2. ON HUMAN INCONSISTENCY | 3. FRIENDSHIP | |||

| 4. LIFE´S PLEASURE | 5. DEATH | ||||

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) was an influential French philosopher of the Renaissance. He was born to a wealthy family in southwest France, where his father, Lord of Montaigne, gave him a rich educational program at home. As a child he was brought up speaking Latin, which became his first language. He studied law at the University of Toulouse, and then served in various important political positions. In his early 30s he was forced by his family to marry. After the death of his father he became Lord of Montaigne, and at the age of 38 he retired to his family estate and started writing The Essays. After almost 10 years of seclusion, he left to travel in Europe, and on his return became the mayor of Bordeaux. He died of quinsy (abscess in the mouth) at the age of 59.

The texts on this page are adapted from Montaigne’s major book The Essays, which he wrote and revised several times between 1571 and his death. This large collection of essays (almost 1300 pages in the complete Penguin edition) is written in a personal and conversational style, with many anecdotes, digressions, autobiographical notes, and quotations from ancient writers. Montaigne attempts here to describe human life – including his own personal life – exactly as it is, honestly and truthfully. He does not try to impose on life big theories, general principles, or lofty ideals. Unlike many thinkers before him who focused on the “high” aspects of life, Montaigne pays special attention to concrete human situations and seemingly trivial details. This includes long passages about his own personality, flaws, and everyday behavior. The result is an unsystematic discussion, personal, often brutally honest, which presents life not as a grand heroic quest, but as a daily struggle with our small human weaknesses. This style of writing had considerable influence on many later writers and thinkers.

| 1. SOLITUDE |

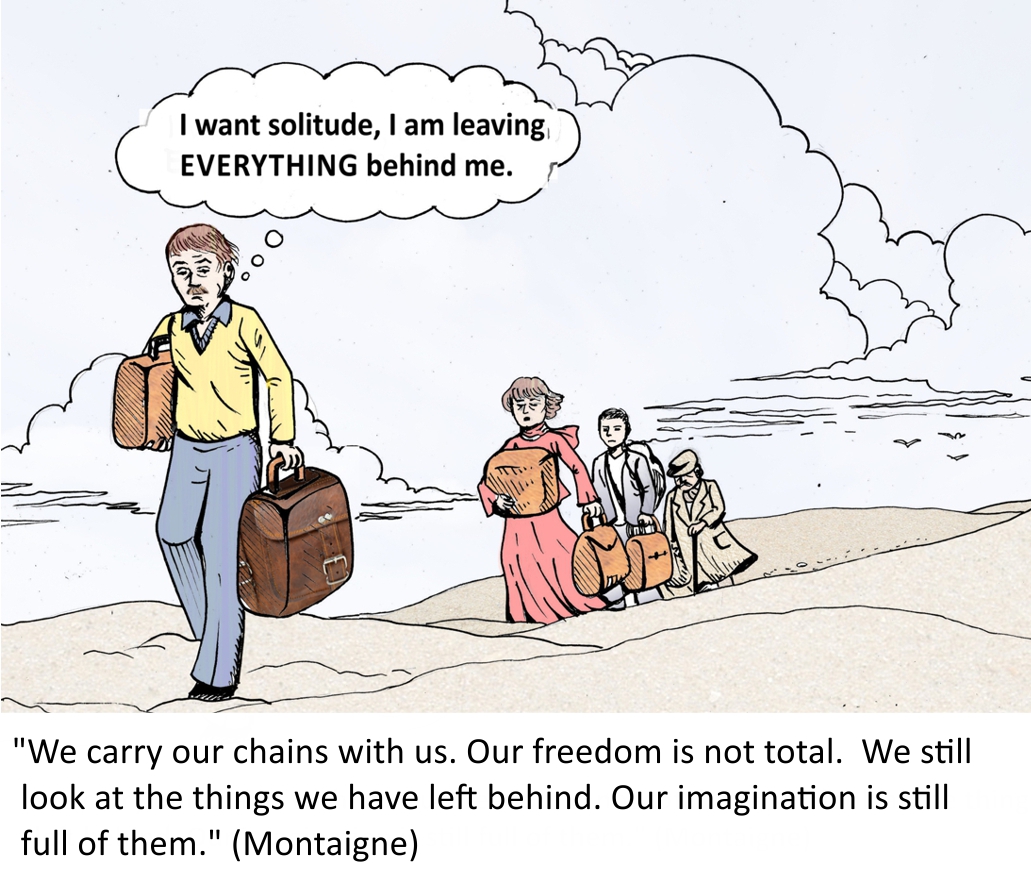

The text below is taken from Book I, Chapter 39 of Montaigne’s Essays, titled “On Solitude.” As typical to his style of writing, he weaves together quotations from ancient writers and his own observations on life, and he pays special attention to people’s narrow-mindedness, self-deception, and confusion. Solitude for him is primarily an inner attitude, not necessarily a physical separation from the world. It means separating our minds from ordinary worries and ambitions, which is something difficult to do.

The text below is taken from Book I, Chapter 39 of Montaigne’s Essays, titled “On Solitude.” As typical to his style of writing, he weaves together quotations from ancient writers and his own observations on life, and he pays special attention to people’s narrow-mindedness, self-deception, and confusion. Solitude for him is primarily an inner attitude, not necessarily a physical separation from the world. It means separating our minds from ordinary worries and ambitions, which is something difficult to do.

There is nothing more unsociable than man, and nothing more sociable: unsociable by his vice, sociable by his nature. […]

Now, our goal, I think, is always the same: How to live in ease and comfort. But people do not always take the right path. Often, they think they have left their occupation behind them, when in fact they have only changed them. Running a family is hardly more troublesome than running a whole country. Whenever our mind finds something to do, it is there entirely. Domestic tasks may be less important, but they are no less of a trouble. Anyway, when we get rid of court and market-place, we do not get rid of the main torments of our life.

(“What drives away worries is reason and prudence, not a place with a good view of the great ocean” – Horace)

Ambition, greed, indecision, fear, and desires do not leave us just because we have exchanged our landscape. […] They often follow us even to monasteries and philosophy schools. Neither deserts, nor caves, nor hair-shirts, nor fasting, can disengage us from them. […]

Socrates was told that a certain man had not been improved by travel. “I certainly believe it,” he replied, “he went together with himself.”

(“Why do we seek lands that are warmed by a foreign sun? Who is the man who by fleeing from his country, can also flee from himself?” – Horace)

If you do not first free both yourself and your mind from the weight of your burdens, moving will only increase the pressure on you, just like a ship’s cargo is less troublesome when held in place. […] That is why it is not enough to get away from the public, and not enough to go to another place. We have to get away from the conditions of the public that are inside us. It is our own self that we have to isolate and possess again.

(“I have broken my chain,” you say. But a dog may break its chain and still carry a long part of it connected to its neck” – Persius)

We carry our chains with us. Our freedom is not total. We still look at the things we have left behind. Our imagination is still full of them. […] Our disease lies in the mind, and it cannot escape from itself.

(“The mind which never escapes from itself is at fault” – Horace)

So we must bring back the mind and drag it into itself. That is the true solitude. It can be enjoyed in towns and in kings’ courts, but more conveniently alone.

Now, since we are trying to live without companions by ourselves, let us make our happiness depend on ourselves. Let us free ourselves from the bonds that tie us to others. Let us gain power over ourselves to live really and truly alone – and to do so with satisfaction.

[…] We have a mind that can turn to itself. It can keep itself company. It has the means to attack, to defend, to receive and to give. Let us not fear that in such a solitude we will suffer from painful emptiness.

(“In solitude, be a company to yourself” – Tibullus)

“Virtue,” says Anisthenes, “satisfies itself, without regulations, words, or actions.” Not even one out of a thousand of our usual activities has anything to do with our self.

[…] We have lived enough for others – let us live for ourselves at least the remainder of our life. Let us bring our thoughts and reflections back to ourselves and to our own well-being. Preparing securely for our own retirement is not an easy matter. It gives us enough trouble even without adding additional concerns. […] Let us pack up our bags and say goodbye to our company in good time. Let us separate ourselves from those traps which connect us to other things and which distance us from ourselves. We must untie those bonds and, from this day onwards, although we may love this thing or that thing, we should not marry anything except ourselves. In other words, let the rest be ours, but not so glued and connected to us so that it cannot be pulled away without tearing a piece of ourselves, skin and all. The greatest thing in the world is to know how to live to yourself.

| 2. ON HUMAN INCONSISTENCY |

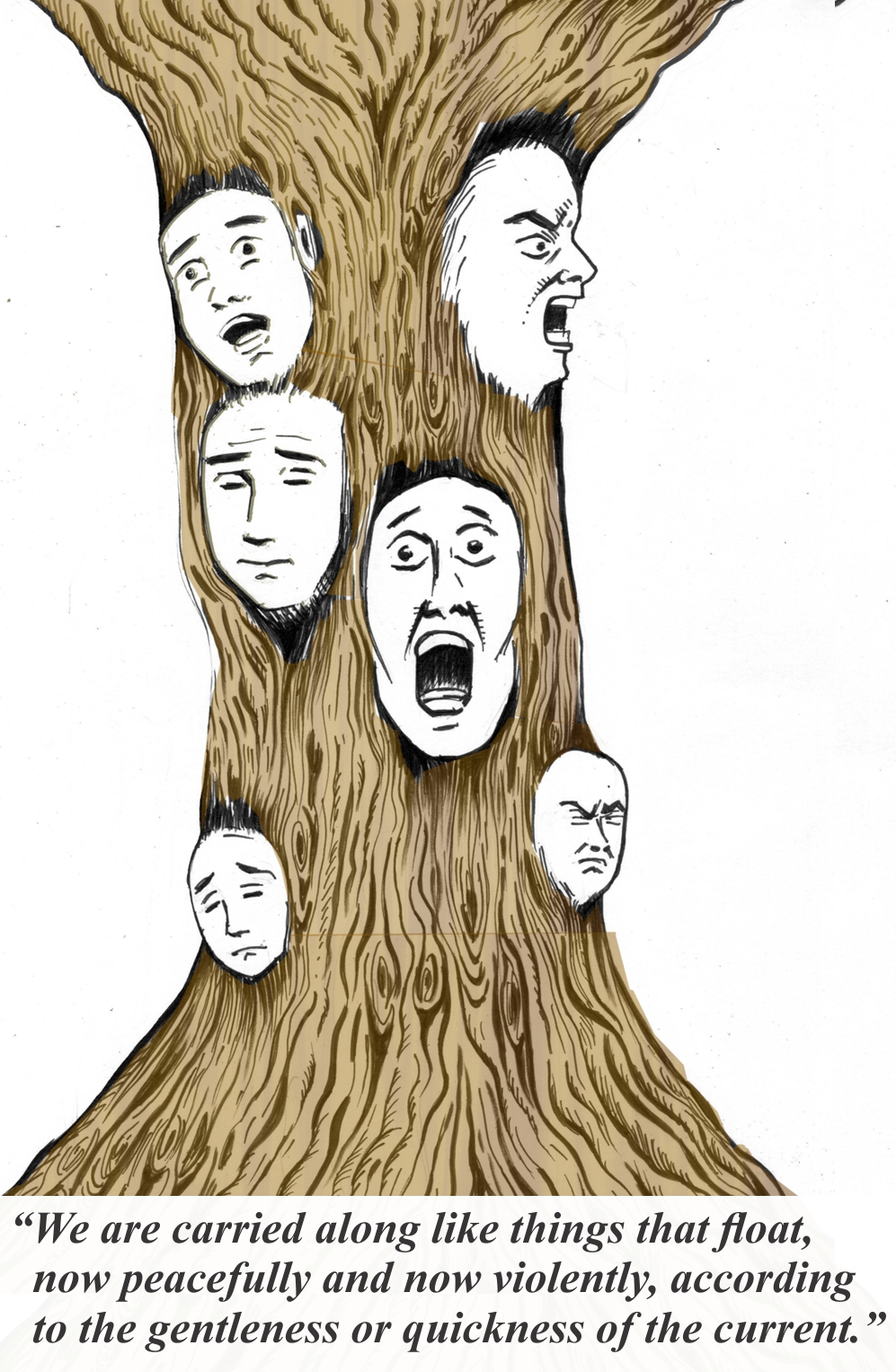

In Book II, Chapter 1 of his Essays, Montaigne criticizes people – including himself! – for changing their mind and behavior all the time. People lack a unified character, a consistent behavior, a clear direction in life. This is unfortunate, because it makes us victims of the circumstances, so that our lives have no integrity and purpose.

In Book II, Chapter 1 of his Essays, Montaigne criticizes people – including himself! – for changing their mind and behavior all the time. People lack a unified character, a consistent behavior, a clear direction in life. This is unfortunate, because it makes us victims of the circumstances, so that our lives have no integrity and purpose.

Here again we see Montaigne’s characteristic style of writing: Focusing on human weakness instead of on high ideals, quoting from ancient writers, and talking about his own life and character. Notice that many of his examples are about battles and fighting, reflecting his political and military involvement in war.

Our normal practice is to follow the inclinations of our desires, left and right, up and down, so we are carried along by the wind of the circumstances. We never reflect on what we want until the moment we want it. We are like the creature that adopts the color of the place in which you put it. What we decided just now we will change very soon, and immediately afterwards we will return to it again. It is all shifting and inconstancy.

( “We are controlled like a wooden puppet by wires pulled by others” – Horace)

We do not go by ourselves, we are carried along like things that float, now peacefully and now violently, according to the gentleness or quickness of the current.

( “Don’t we see them always like that, uncertain what they want, always looking for something new, as if they could get rid of the burden?” – Lucretius)

Every day a new idea, and our moods change with the changes of the weather.

[…]

The man you saw yesterday so brave, don’t think it strange if tomorrow you will find him a great coward. He was moved by anger, or need, or his friends, or wine, or the sound of a trumpet. This was not courage formed by reason, but by accidental circumstances. It is no wonder if he would become quite different because of contrary circumstances.

The flexible changes and contradictions are so visible in us, that some people believe that we have two souls. Others believe that two angels accompany us and influence us, one towards good, the other towards evil, according to their nature and inclination, since such sudden changes cannot flow from the same source.

As for me, the wind of every accidental event carries me along according to its orientation. And moreover, I also agitate and disturb myself by the instability of my posture. Anyone who looks carefully at himself will hardly find himself twice in the same state. I give my soul sometimes this face and sometimes that face, depending on which side I turn to her. I speak about myself in diverse ways because I look at myself in different ways. All kinds of contradictions can be found in me, one way or another: shy, rude, chaste, lustful, talkative, silent, tough, delicate, clever, dull, melancholic, pleasant, lying, truthful, learned, ignorant, generous, stingy, or reckless. I can see all of these in myself, depending on which way I turn. And anyone who studies himself deeply will find in himself, and even in his judgement, these quick shifts and conflicts. I have nothing to say about myself as a whole, simply and completely, without mixture and confusion.

[…] Therefore, one courageous action must not be taken as proof that a man really is brave. A man who is truly brave will always be brave on all occasions. If a man’s courage was a habit and not a sudden outburst, he would always be so in all situations – when he is alone just as with his comrades, in the competition field as on the battlefield. Because, whatever people say, there is not one courage for the street and another courage for the field. He would bear with equal courage an illness in his bed and a wound in battle, and he would be no more afraid of dying at home than in an attack. We would never see the same man charging with brave confidence into a gap in the enemy army, and then torment himself like a woman over the loss of a lawsuit or a child. If a known coward is resolute in the necessities of poverty, if a man shrinks at the sight of a barber’s razor but then rushes fearlessly against his enemy’s swords, then the action deserves praise but not the man.

[…]

No wonder, said an ancient thinker, that chance has so much power over us, since it is by chance that we live. Anyone who has not designed his life towards a definite purpose cannot possibly arrange his individual actions properly. It is impossible to put the pieces together if you do not have in your mind the idea of the whole. What is the use of having paints, if you do not know what to paint? Nobody in fact sketches a definite plan for his life, we only deliberate on the pieces. The bowman must first know what he is aiming at, and only then prepare his arm, his bow, string, arrow, and motion towards this goal. Our projects go astray, because they are not directed at a clear target. No wind can help a seaman who has no port as his target.

| 3. FRIENDSHIP |

Chapter 28, Book One of Montaigne’s Essays is devoted to the topic of friendship. In the following excerpts, slightly adapted from this chapter, Montaigne explains that true friendship is different both from erotic love and from common friendship. He distinguishes between two kinds of friendships: ordinary relations which we call friendship but are no more than being together for the sake of comfort, and the rare friendship in which the two souls mix together. Montaigne’s idea is based on his own deep friendship with Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563), a French poet and philosopher whose early death saddened Montaigne deeply.

Chapter 28, Book One of Montaigne’s Essays is devoted to the topic of friendship. In the following excerpts, slightly adapted from this chapter, Montaigne explains that true friendship is different both from erotic love and from common friendship. He distinguishes between two kinds of friendships: ordinary relations which we call friendship but are no more than being together for the sake of comfort, and the rare friendship in which the two souls mix together. Montaigne’s idea is based on his own deep friendship with Étienne de La Boétie (1530-1563), a French poet and philosopher whose early death saddened Montaigne deeply.

We cannot compare friendship to the passion we feel towards women, even though it is an act of our own choice, nor can we put them in the same category. I must admit that the fire of passion –

(“I am not acquainted with the goddess who mixes a sweet bitterness with my love” – Catullus )

– is more active, eager, and sharp. But this fire is more impulsive, capricious, fluctuating, and changing. It is a heated fire subject to attacks and declines, which only captures one part of us. The love of friendship, in contrast, is a general and universal warmth, mild and smooth, a warmth that is constant and stable, gentle and even, without sharpness or roughness. Moreover, romantic love is a frantic desire for what escapes from us:

(“Like the hunter who chases the hare through heat and cold, on the mountain and in the valley, yet once he has captured it he does not think much of it, and only delights in chasing what flees from him” – Ariosto )

As soon as love enters the domain of friendship, in other words when the wills of two people work together, it weakens and is gone. To enjoy erotic love is to lose it, since its purpose is the body, and therefore after a while you have enough of it. With friendship, in contrast, greater enjoyment and greater desire go together. When we enjoy it, it only grows and is nourished and improved, since it is spiritual, and the soul is purified through practice.

[…]

What we normally call friends and friendships are no more than acquaintances and familiarity based on chance or some purpose, through which our souls support each other. In the friendship I am talking about, the two souls are mixed and mingled in such a universal mixture, that the border-line that connects them together into one piece is erased and cannot be found. If you press me to explain why I loved [my friend La Boétie], I find that it cannot be expressed except by replying: because it was him, because it was me.

[…]

In such a noble relationship, it is not worth paying attention to the services and favors which the friends give each other, and which nurture other kinds of friendships, because of the total mixture of the two wills. Just as the friendly love which I feel for myself is not increased by the help which I give to myself, and just as I feel no gratitude for any favor which I do to myself, likewise the union of such friends, since it is truly perfect, leads them to lose any awareness of such services. It leads them to hate and expel from between them all notions of division and difference, such as favor, duty, gratitude, request, thanks and the like. Everything is truly common to both of them: their wills, their property, wives, children, honor and lives. Their relationship is that of one soul in two bodies, according to Aristotle’s very appropriate definition, so they cannot lend or give anything to each other. […] In this kind of friendship, if one of us could give something to the other, then the receiver would be the one who would put his companion under an obligation. Because each of them seeks, more than anything else, the good of the other, so that the one who provides the opportunity to give is in fact more generous, since he gives his friend the joy of doing for him what he most desires to do.

[…]

In truth, if I compare all the rest of my life – although by the grace of God I have lived it sweetly and easily […] – if I compare it, I say, to those four years in which it was granted to me to enjoy the sweet companionship and fellowship of a man like that, it is nothing but smoke and ashes, a dark and tedious night.

Since that day when I lost him […] I merely drag myself wearily on. The pleasures which are offered to me do not comfort me – they double my sorrow at his loss. In everything we were halves; I feel I am stealing from him:

(“Nor is it right for me to enjoy pleasures, I decided, while he who shared things with me is absent from me” – Terence )

I was already so accustomed to being, in everything, one of two, that I now feel I am no more than a half.

| 4. LIFE’S PLEASURES |

The last chapter of Montaigne’s Essays, titled “On Experience,” is especially long, about sixty pages in the English edition. Here Montaigne discusses what experience has taught him about how to live life. The chapter covers a variety of topics, including health and medicine, the practice of law, daily habits, sleep, eating, and the pleasures of life. As he explains in the first few pages of the chapter: “I study myself more than any other subject. That is my metaphysics, that is my physics.” And a bit later: “I would rather be an expert on me than on Cicero.”

The last chapter of Montaigne’s Essays, titled “On Experience,” is especially long, about sixty pages in the English edition. Here Montaigne discusses what experience has taught him about how to live life. The chapter covers a variety of topics, including health and medicine, the practice of law, daily habits, sleep, eating, and the pleasures of life. As he explains in the first few pages of the chapter: “I study myself more than any other subject. That is my metaphysics, that is my physics.” And a bit later: “I would rather be an expert on me than on Cicero.”

Montaigne does not like high spiritual ideals of purity. For him, we must acknowledge the fact that we are human beings, flesh and blood. Our bodily functions and needs are part of who we are. As he says at around the middle of this chapter: “Kings and philosophers shit, and so do ladies.” It is therefore not surprising that Montaigne believes in enjoying the pleasures of life. While we should not be slaves of excessive pleasures, we should also not try to deny them.

I, who am always down-to-earth, dislike this inhuman wisdom which wants us to despise and hate the care of the body. I regard detesting natural pleasures just as wrong as loving them too much. Xerxes, who was surrounded by every human delight, was an idiot to offer a reward to anybody who would invent a new pleasure for him. But a man is not less idiotic if he rejects the pleasures which nature offers him. We should neither run after them nor avoid them, but accept them. I confess that I accept them with a little too much enthusiasm and gratitude, and I easily allow myself to follow my natural inclinations. We don’t need to exaggerate their emptiness.

[…]

When I dance, I dance. When I sleep, I sleep. And when I walk alone in a beautiful orchard, although my thoughts are sometimes occupied with external things, part of the time I bring them back to my walk, to the orchard, to the sweetness of my solitude, and to myself. Nature, like a mother, provided for us that the actions she has imposed on us as necessities would also be pleasurable. And she invites us to them not only through reason but also through desire. To violate her laws is wrong.

[…]

Greatness of soul consists not so much of pressing upward and forward as of knowing how to govern yourself and limit yourself. It regards anything that is enough as plenty, and it demonstrates itself by preferring moderate things to outstanding things. Nothing is so beautiful and right as behaving like a person should, and no learning is as hard as knowing how to live this life naturally and well. Of all the illnesses we have, the most barbarous is to despise our being.

If anybody wants to isolate his spirit to avoid contagion, then by all means let him do so, if he can, when the body is not well. But otherwise, he should help and favor his body, and not refuse to participate in its natural pleasures. He should enjoy the body as if it was a spouse and treat it in moderation, if he is wise enough, so that out of carelessness those pleasures would not get mixed with displeasure.

[…]

I do not wish life to be without the need to eat and drink, and it wouldn’t be a smaller error to wish that this need was increased and doubled:

( “A wise man is the keenest seeker for the riches of nature” – Seneca)

Nor do I wish that we could survive by putting in our mouths the little drug which Epimenides used to ease his hunger and keep himself alive. Nor do I wish that we could, without feeling anything, produce children with our fingers or our heels […], nor that the body should be without desire and without excitement. Such complaints are ungrateful and wicked. I accept fully and thankfully what nature has done for me. I am pleased with it and am proud of it. You do wrong to the great and almighty Giver if you refuse his gift, abolish it, or disfigure it. Since he is entirely good, he has made everything good:

( “All things that are according to nature are worthy of esteem” – Cicero)

[…]

Aesop, that great man, saw his master pissing while he was walking. “And what’s next?” he said, “Should we now shit when we run?” Although we should manage our time, there still remains a lot of time that we should leave idle and unused. Our mind does not easily accept that it has many other hours to do its business without having to disconnect itself from the body during the short time which the body needs for its necessities.

People want to put themselves outside themselves and escape their humanity. It is madness: Instead of transforming themselves into angels, they transform themselves into beasts. Instead of elevating themselves, they go lower. Those transcendental absurdities scare me, as do great unapproachable heights. […] The noble inscription with which the Athenians honored Pompey’s entry into their city agrees with me: “You are a god insofar as you regard yourself a man” (Horace).

It is an accomplishment, absolute and divine so to speak, to know how to enjoy our being as we should. We seek other qualities because we do not understand the use of the qualities we have. And we go out of ourselves because we don’t know how to reside there. It’s a big deal to stand high on stilts! – because even on stilts we must always walk with our legs. And upon the most elevated throne in the world, we are still sitting on our asses.

The most beautiful lives, in my opinion, are those which conform to the common model, which is human and ordered, without miracle and without extravagance.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.