The Philo-Practice Agora

The electronic library for philosophical practitioners from around the world

LIST OF PHILOSOPHERS

THEMES ON THIS PAGE:

| 1. COMMON SENSE | 2. HUMAN POWERS | 3. GRANDEUR |

Thomas Reid (1710-1796) was a Scottish philosopher and the father of modern “common-sense philosophy.” Like his father, he first became a minister of the Church of Scotland. Later, thanks to a philosophy essay which he wrote, he was invited to teach philosophy at the University of Aberdeen. During the rest of his long life he published three books, which dealt with epistemology, the human mind, willing and acting, ethics, and other topics. His philosophy was popular in certain historical periods, but his popularity declined in the 20th century. He died at the age of 86.

Common-sense philosophy regards common sense as the starting point of philosophical investigations and as their foundation. As a major proponent of this approach, Reid was opposed to the philosophers who were popular in his time. Throughout his writings he attacked their “absurd” views, which go against what every normal person assumes. Their claims that the material world does not exist, that colors and tastes are subjective experiences in the mind, that what we see around us is not the world but rather ideas in our mind – these and similar views are false because they contradict everyday beliefs. Philosophy should be faithful to the principles of common sense, which we cannot prove but which are at the basis of life.

| TOPIC 1. COMMON SENSE |

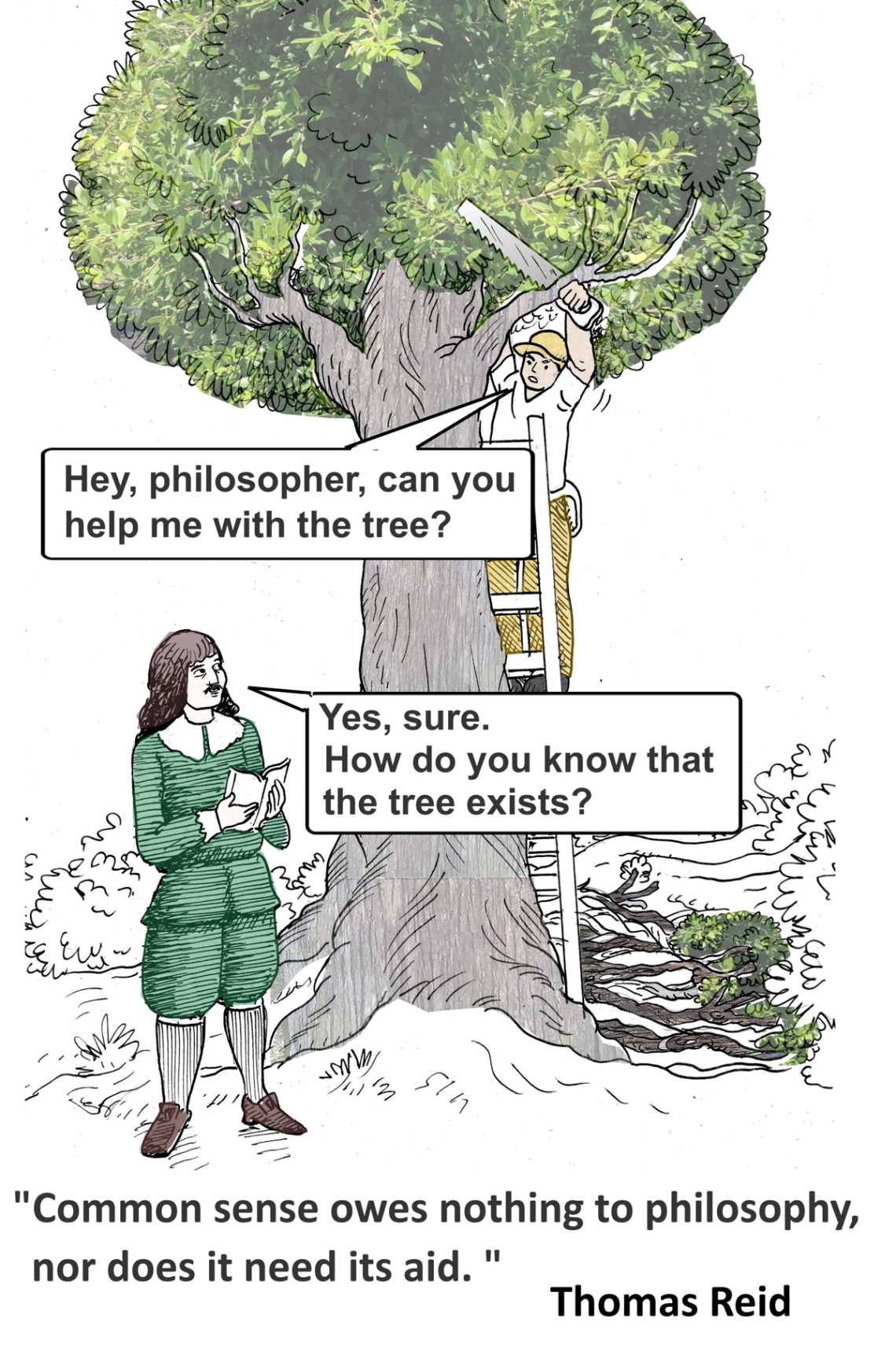

Reid’s defense of common sense appears in many places throughout his writings. He often ridicules philosophical theories that contradict it, especially those of Descartes, Malebranche, Locke, Hume and Berkley. He enjoys making fun of their ideas, which every normal person would find crazy. He points out that nobody really believes in these ideas, including those philosophers themselves in their everyday, non-philosophical moments.

Reid’s defense of common sense appears in many places throughout his writings. He often ridicules philosophical theories that contradict it, especially those of Descartes, Malebranche, Locke, Hume and Berkley. He enjoys making fun of their ideas, which every normal person would find crazy. He points out that nobody really believes in these ideas, including those philosophers themselves in their everyday, non-philosophical moments.

The following passages are taken from his first book, An Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense, published in 1764. (Several old English expressions were changed to modern ones.) Each chapter in this book is devoted to one of the human senses: smelling, tasting, hearing, touching, seeing. This is probably one of the only philosophy book that discusses in detail the senses of smell, taste, and touch.

From the INTRODUCTION

Descartes, Malebranche and Locke have used their talents and skill to prove the existence of a material world, and with very bad success. Poor uneducated people believe, without doubt, that there is a sun, moon and stars; an earth that we inhabit; country, friends and relations that we enjoy; land, houses and furniture that we possess. But philosophers, who pity the naivety of ordinary people, decide to have no faith in anything that is not based on reason. They ask philosophy to give them reasons to believe in those things which all humankind have believed without having reasons for it. One would expect that in such important matters, the proof would not be difficult, but it is the most difficult thing in the world. Because these three great men, with the best good will, have not been able to find in all the treasures of philosophy one argument that can convince a reasonable man of the existence of anything except himself.

[…] In this unequal contest between common sense and philosophy, philosophy will always come out both with dishonor and loss. And it can never prosper until this opposition ends, until philosophy stops trying to invade the territory of common sense, and a cordial friendship is restored. Because in fact, common sense owes nothing to philosophy, nor does it need its aid. But on the other hand (if I may be permitted to change the metaphor), philosophy has no other roots except the principles of common sense. It grows out of them and receives its nourishment from them. When it is disconnected from this root, its honors decline, its sap is dried up, it dies and rots.

From CHAPTER 5: ON TOUCH

Thus, the wisdom of philosophy is set up against the common sense of humankind. It pretends to demonstrate, a priori, that there cannot be such thing as a material world; that the sun, moon, stars and earth, vegetable and animal bodies cannot be anything but sensations in the mind, or images of those sensations in the memory and imagination; that (like pain or joy) they cannot exist when nobody thinks about them. Common sense cannot regard this as anything but a kind of metaphysical craziness. And it concludes that too much learning tends to make people mad, and that anyone who seriously entertains this belief, even if in other respects he is a very good man, is like a man who believes that he is made of glass, and he surely has a soft place in his understanding, and has been hurt by too much thinking.

This opposition between philosophy and common sense tends to have a very unhappy influence on the philosopher himself. He sees human nature in an odd, unfriendly and shameful light. He considers himself, and the rest of his kind, as born under a necessity of believing ten thousand absurdities and contradictions, and as given such a tiny amount of reason that is barely sufficient to make this unhappy discovery – and that’s all the fruit of his profound speculations. Such notions of human nature tend to weaken every nerve of the soul, to embarrass every noble purpose and feeling, and to spread melancholy over everything. If this is wisdom, then let me be deluded with the common people.

[…] What is the point of letting philosophy decide against common sense on this or any other matter? The belief in a material world is older, and has more authority, than any principles of philosophy. It rejects the tribunal of reason, and it laughs at all the artillery of the logician. It still has the supreme authority despite all the edicts of philosophy, and reason must bow down and obey its commands. Even the philosophers who rejected the notions of an external material world confess that they find themselves forced to submit to their power.

I therefore think that it would be better to turn this necessity into an advantage: Since we cannot get rid of the vulgar notion of an external world, let us make peace between them as well as we can. Because even if reason is irritated and nervous with this yoke, it cannot throw it off. If it refuses to be the servant of common sense, it must be its slave.

| TOPIC 2. HUMAN POWERS |

In his three philosophy books, Thomas Reid investigated many aspects of the human mind, always trying to be faithful to common sense. Other philosophers of his time, like Malebranche, Locke, Hume and Berkeley, often rejected common sense in the name of reason. When they encountered a phenomenon they couldn’t explain by reason (the self, causation, material objects, etc.), they typically concluded that it is an illusion, and that it doesn’t really exist.

In his three philosophy books, Thomas Reid investigated many aspects of the human mind, always trying to be faithful to common sense. Other philosophers of his time, like Malebranche, Locke, Hume and Berkeley, often rejected common sense in the name of reason. When they encountered a phenomenon they couldn’t explain by reason (the self, causation, material objects, etc.), they typically concluded that it is an illusion, and that it doesn’t really exist.

This seemed to Reid totally unacceptable. When he encountered a common idea which reason cannot explain, he did not conclude that common sense is confused or mistaken. Rather, he concluded that it is a fact that cannot be analyzed and explained. One famous example is the idea of the Self: While Hume claimed that the self is an illusion, Reid claimed that the self certainly exists, as is testified by common sense, but it is a “simple” fact that cannot be analyzed into elements, and therefore cannot be explained.

The following text is about another phenomenon which Reid addresses in this way: The power of the will. We cannot explain how our will moves our body or influences our thoughts. Yet, unlike philosophers like Malebranche and Hume who doubted the power of the will, Reid accepts it as an evident fact that cannot be explained. Our power is small and limited, but through it we can do great deeds, both good or evil.

The text below is adapted to modern English from Reid’s last book, Essays on the Active Powers of Man (1788), from the first essay in the book titled “The active powers in general.”

From CHAPTER 7: “The Extent of Human Power”

Some people receive more power than others, and a person may have more power at one time and less at another. […] But every person who can be held responsible must have more or less of it. Because it would be absurd to hold a person responsible, to approve or disapprove of his behavior, if he had no power to do good or bad. No axiom of Euclid appears more evident than this.

[…]

The effects of human power are either immediate, or they are more remote. The immediate effects, I think, can be divided into two groups: We can give certain motions to our own bodies, and we can give a certain direction to our own thoughts. Whatever we can do beyond this, we must do in one of these two ways, or both. We cannot produce motion in any body in the universe, except by first moving our own body as an instrument. And we cannot produce thought in any other person, except through thought and motion in ourselves.

[…] Regarding what comes after the will and before the contraction of the muscle [= how our will produces our action], we know nothing and can say nothing about it. We don’t even know how our will produces those immediate effects of our power. We don’t perceive any necessary connection between our will and effort, and the bodily motion that follows them. […] This is one of the wonders of our structure, which we have reason to admire. But explaining it is beyond the reach of our understanding.

[…]

Even though the immediate effects of human power may be small, its more remote effects are very considerable. In this respect, the power of a person may be compared to the Nile, the Ganges, and other great rivers, which cut through the landscape and go through vast regions, sometimes bringing to many nations great benefit and at other times great harm. Yet, when we trace those rivers to their source, we find that they originate from small fountains and creeks.

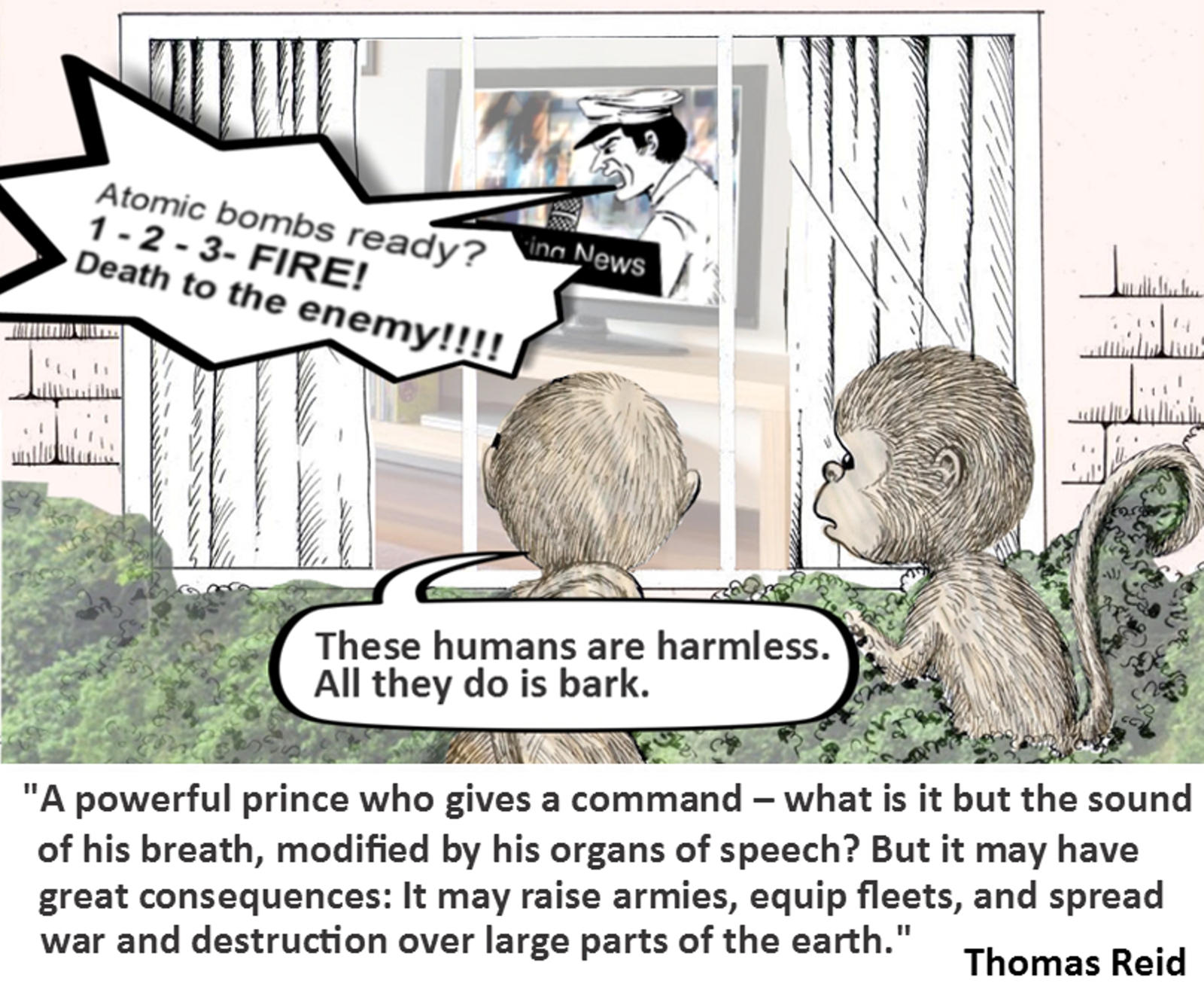

A powerful prince who gives a command – what is it but the sound of his breath, modified by his organs of speech? But it may have great consequences: It may raise armies, equip fleets, and spread war and destruction over large parts of the earth. The most insignificant person has considerable power to do good, and even more power to hurt himself and others. From this, I think, we may conclude that although the degeneracy of humankind is great, and we should be sorry for it, yet people in general tend to use their power to do good more than to hurt their fellow-humans. Doing harm is much more in their power than doing good, and if they were much inclined to do it, human society could not have survived, and our species would have disappeared from the earth.

[…]

If we consider the changes that a person may make to his own mind, and to the minds of others, they appear to be great. To his own mind he may make great improvement by acquiring the treasures of useful knowledge, the habits of skill in arts, the habits of wisdom, prudence, self-control, and every other virtue. It is in our nature that those qualities which elevate and dignify human nature are acquired by proper efforts; and contrary behavior creates the qualities that lower our nature below the level of beasts.

Great effects may be produced through human power even on the minds of others: through good education, proper instruction, persuasion, good example, and through the discipline of laws and government. It cannot be doubted that these have often had great and good effects on civilization and improved individuals and nations. […] What a noble and divine use of human power is given to us! How should it arouse the ambition of parents, of instructors, of lawgivers, of magistrates, of every human in his station, to contribute his part towards the accomplishment of such a glorious goal!

| TOPIC 3. GRANDEUR |

In his second book, Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (1785), Reid explores human reason, memory, and thought. But at the end of the book, he devotes an essay to beauty and grandeur. By “Grandeur” he means the quality that makes something great, excellent, sublime, awesome, admirable. This includes a wide range of meanings, including those of “an awesome landscape,” “a profound work of art,” “a great person,” “a sublime symphony,” etc. Faithful to his common sense-approach, Reid argues that grandeur is not just a subjective feeling in our mind, but a real quality that exists objectively. After all, in everyday life, before we start philosophizing, we find greatness in a novel or in a symphony, not in our own subjective feelings. Our feelings of admiration are only our personal response to objective grandeur.

In his second book, Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man (1785), Reid explores human reason, memory, and thought. But at the end of the book, he devotes an essay to beauty and grandeur. By “Grandeur” he means the quality that makes something great, excellent, sublime, awesome, admirable. This includes a wide range of meanings, including those of “an awesome landscape,” “a profound work of art,” “a great person,” “a sublime symphony,” etc. Faithful to his common sense-approach, Reid argues that grandeur is not just a subjective feeling in our mind, but a real quality that exists objectively. After all, in everyday life, before we start philosophizing, we find greatness in a novel or in a symphony, not in our own subjective feelings. Our feelings of admiration are only our personal response to objective grandeur.

More precisely, Reid argues, the grandeur is not of the book but of the writer who wrote it, not of the symphony but of the musician who composed it. For example, when I admire an amazing poem I am really admiring the skills and wisdom of the poet. This is why he argues (see the beginning of the text below) that the grandeur we find in nature is really the grandeur of the creator who created nature.

From Essay 8: ON GRANDEUR

New and uncommon things influence us with a pleasant surprise, which arouses and energizes our attention to the object. But this emotion soon declines if the only thing that keeps it going is newness, and so it leaves no effect upon the mind.

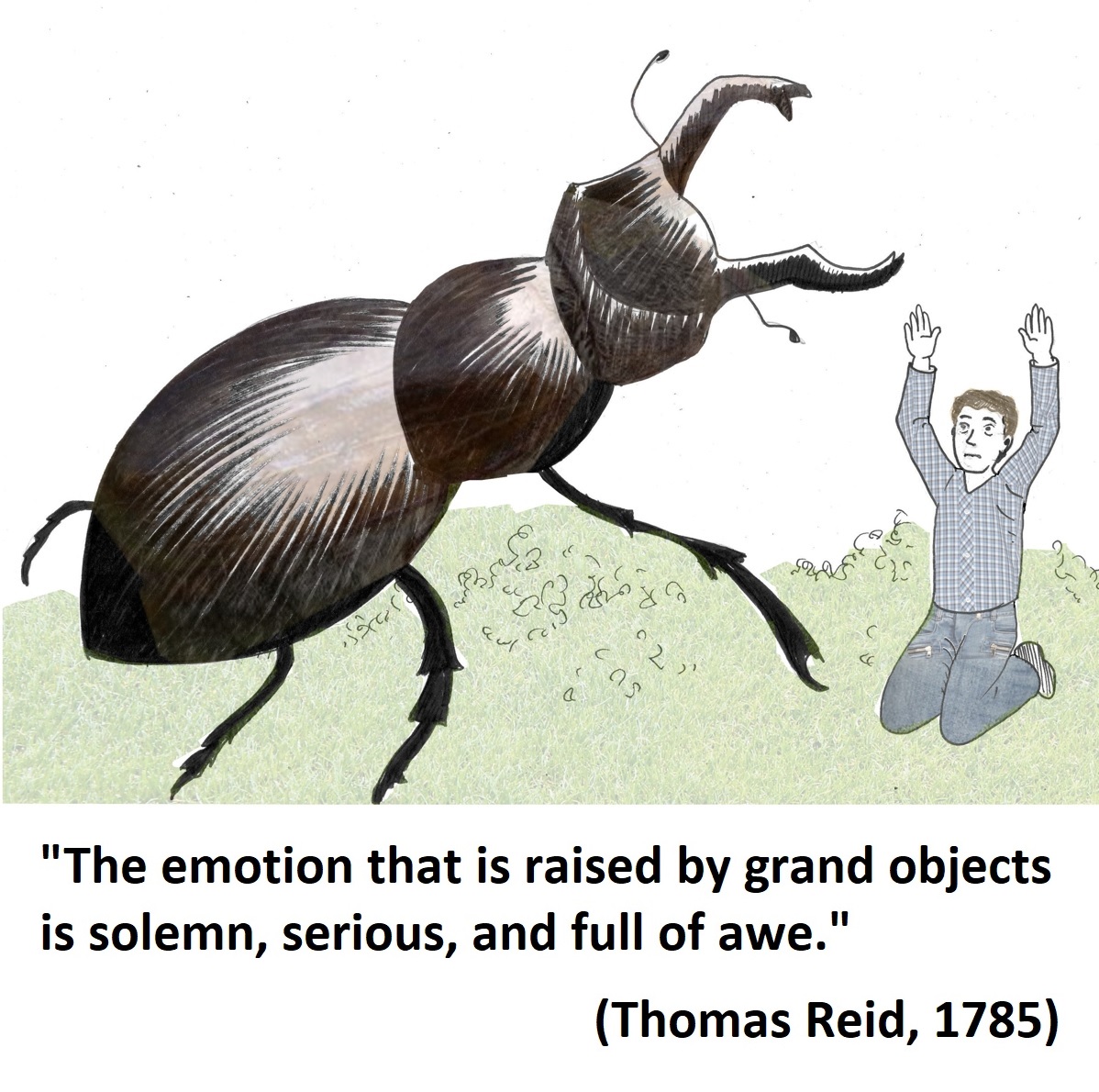

The emotion that is raised by grand objects is solemn, serious, and full of awe. Out of all the objects of contemplation, the Supreme Being is the most grand. His eternity, his immensity, his irresistible power, his infinite knowledge and absolute wisdom, his consistent justice and goodness… all these fill the greatest capacity of our soul, and they reach far beyond our comprehension.

The emotion which this grandest of all objects raises in the human mind is what we call devotion. It is a serious, recollected state of mind, which inspires magnanimity, and inspires us to do the most heroic acts of virtue.

The emotion produced by other objects which we call grand, although grand in a lesser degree, is a similar devotion in its nature and impact. It tends to be serious, it elevates the mind above its usual state to a kind of enthusiasm, and it inspires magnanimity, and contempt towards what is low.

This, I believe, is the emotion which the contemplation of grand objects arouses in us. Let us now consider what this grandeur is.

It seems to me that it is nothing else but an excellence of some kind which deserves our admiration. There are some qualities of mind which have a real and intrinsic excellence, compared with their opposites. They are, in any degree, the natural objects of esteem, but when they are in a high degree, they are objects of admiration. We value them because they are intrinsically valuable and excellent.

The spirit of modern philosophy wants us to think that the value we put on things is only a feeling in our minds, and not anything inherent in the object; and that our [psychological] constitution makes us value some things and despise others. […] But if we listen to the dictates of common sense, we must be convinced that there is real excellence in some things, independently of our feelings or constitution. No doubt, it depends on our constitution whether we do or don’t perceive excellence where it really is. But the object has its excellence from its own constitution, and not from ours.

The common judgment of humankind appears in the language of all nations, which uniformly ascribes excellence, grandeur, and beauty to the object, and not to the mind that perceives it. And I believe that here, like in most other things, we will find that the common judgment of humankind and true philosophy in agreement.

Isn’t power, by its very nature, more excellent than weakness? Knowledge more than ignorance? Wisdom more than foolishness? Courage more than cowardice? Is there no intrinsic excellence in self-command, in generosity, in public spirit? Isn’t friendship a better feeling than hatred, and noble competition than envy?

[…] There is, therefore, a real intrinsic excellence in some qualities of mind, such as power, knowledge, wisdom, virtue, magnanimity. These, in every degree, deserve esteem, but when they are in an exceptional degree they deserve admiration. And what deserves our admiration we call grand. When the mind contemplates exceptional excellence, it feels a noble enthusiasm which inspires it to imitate what it admires.

[…] A great creative work is a work of great power, great wisdom, and great goodness, well-designed for some important end. But power, wisdom, and goodness, are, speaking precisely, the qualities of a mind. We ascribe them to the work only figuratively, but they are really inherent in the creator. Thus, the grandeur which we ascribe to the work is, more precisely, inherent in the mind that made it.

[…] Overall, I humbly believe that true grandeur is excellence to such a high degree that it can raise an enthusiastic admiration; that this grandeur is found originally in qualities of mind; that we notice it in the objects we perceive only by reflection, just as the light which we perceive in the moon and planets is really a reflection of the light of the sun.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.